Many of my friends live in the UK, and have now been put under a “Tier 4” lockdown in response to rising case numbers, particularly in London and the South-East of England. Along with this news is the reporting of a “new strain” of the SARS-CoV2 virus thought to be responsible for this surge. The Interwebs are now aflame with doom and gloom scenarios of vaccine futility, global spread, and the basic fear that new = bad. Now, this is still 2020 so of course people can be forgiven for feeling that way, but if anything the facts are reassuring.

The simple truth is, the UK would have to enact harder lockdown efforts based purely on the rise in cases recently, regardless of whether or not a new strain was identified genetically. It is a total misrepresentation to suggest that the UK is locking down BECAUSE of a new strain – they are locking down because of a rise in cases. New strains have been reported throughout the pandemic, most notably the 614G mutation that arose in the spring but is now the predominant strain worldwide. In many ways the panic surrounding THIS particular strain is due to awareness rather than any hard data.

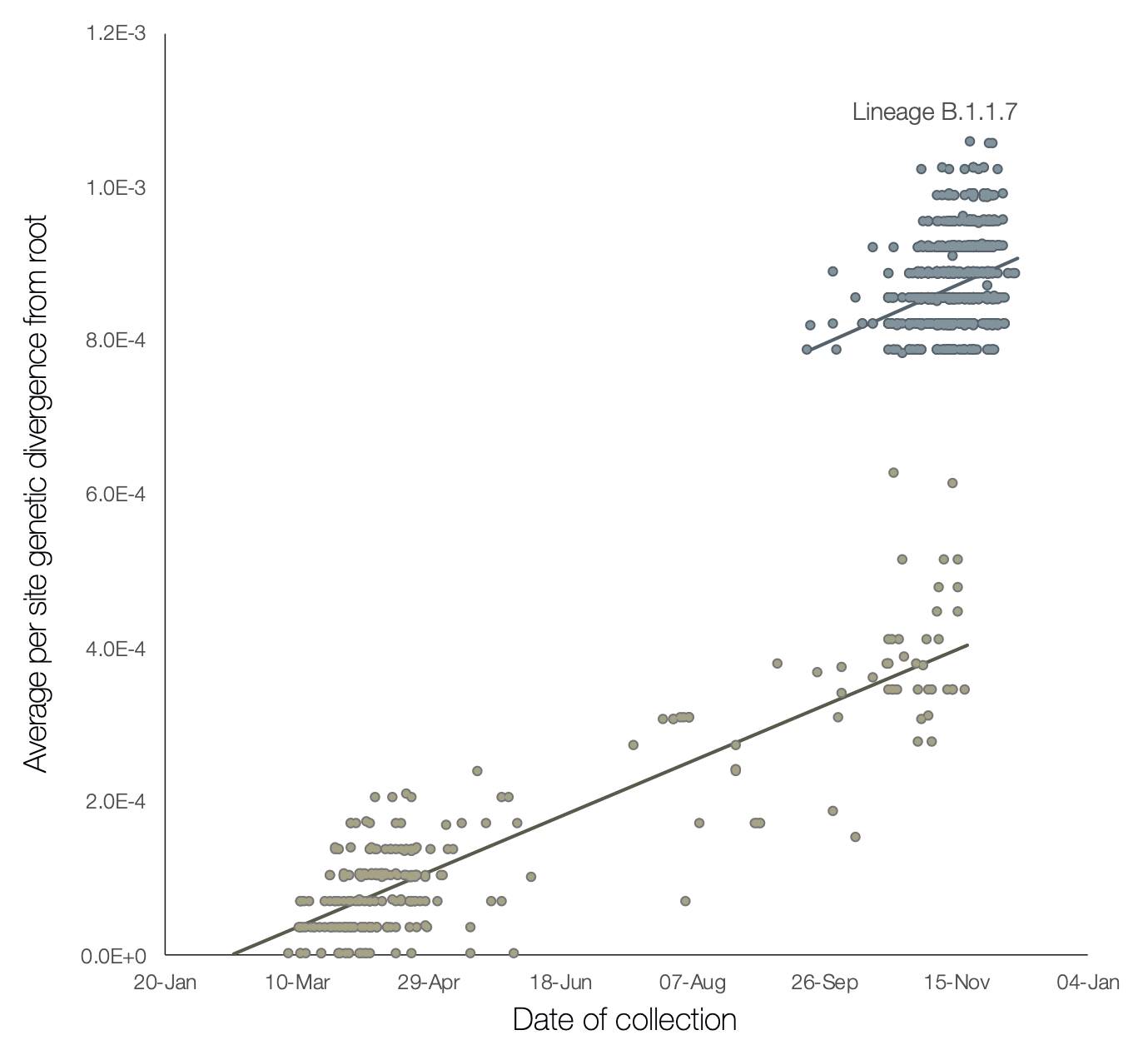

There is no doubt that the UK has failed at containing COVID-19, but not only is there a second wave of infections starting from September, there is a sharp 3rd spike over the last few weeks. This is truly an unusual graph, and not one that I’ve seen quite so dramatically elsewhere. A report in the British Medical Journal, and further outlined elsewhere tells more of the story, and perhaps explains that new surge in cases. A graph from that last paper by Rambaut et al shows the frequency of detection over time, and the genetic divergence, of SARS-CoV2 isolates in the UK.

Firstly, if you look at the lower cluster, it shows a slow increase in genetic diversity over time, as expected with this virus anyway (1-2 mutations per month). You can’t really compare disease incidence with this graph because only a subset of isolates are going to get sequenced, but you still get the sense that there was a peak in the spring and less over the summer. The cluster in the top-right is entirely distinct – firstly the diversity is way off from the trendline of the previous infections (which are still ongoing) but also the proportion of current isolates coming from this new cluster seems to be high.

The obvious worry is that the new strain is more infectious – but the evidence for that is still circumstantial. Just because more cases are occurring doesn’t mean the new strain is responsible – after all, it also true that more widespread infection will make the appearance of significant mutations more likely. There are several mutations identified in this strain within the spike protein that could, in theory, render it more infectious by altering it’s receptor-binding properties (after all, that’s thought to be why SARS-CoV2 is more infectious that the original SARS). The affected sites DO appear to alter receptor-binding and entry locations, and so there is a little more of a “smoking gun” regarding infectivity than merely seeing high numbers of cases – see the section “Potential biological significance of mutations” in the Rambaut paper.

Importantly, there is apparently not sufficient change in the S protein to affect the likely vaccination targets…although honestly we will have to see how the real world data looks with that. The Pfizer vaccine is a whole-protein target with many more places for the immune response to target than just the receptor-binding area at the top. Worries that this “new strain” will render the entire vaccination effort meaningless are not founded in any fact at this point, since all this virus really is, is a slightly different strain of the same virus, to which it remains about 99% the same (8 mutations in a protein that is over 1200 amino acids long…)

And lastly, there is the intriguing finding that some of this new lineage of virus contains a series of mutations in a gene called “ORF8” (simply, open-reading frame 8). This gene is thought to be involved in hiding from the host immune response, by downregulating the protective antiviral system called MHC-1. Similar mutations have been reported before, and not surprisingly the virus is less dangerous. In a small series from Singapore, 28% of patients with wild-type COVID required oxygen, compared to 0% of those with the ORF8 deletion. Rambaut et al hypothesize that this UK strain arose from prolonged infection in an immune-compromised host, perhaps having been treated with multiple antiviral therapies. This would explain the cluster of mutations all appearing together, as well as the potential loss of ORF8 (since it would pose no advantage to the virus to keep it).

And let’s have a quick look at the daily deaths from the UK. While the daily cases are 5-times higher than back in the spring (25,000/day versus 5000/day), the daily deaths are half as high (500/day versus 1000/day). While this reflects a mix of improved management of cases, perhaps different age demographics, it also begs the question as to whether the virus itself is simply less dangerous than it was before.

Looking at this information, I see it that while this may indeed be a new strain, it is not a reason to panic. We have no real reason to suspect that it’s going to affect the vaccine efforts, and absolutely no reason to suspect that it’s any more dangerous than before. In fact, there is a suggestion that it may be LESS dangerous than earlier circulating strains. We should be thankful that scientists are tracking and reporting this data, and remember that any new mutations that do render the current vaccine ineffective can be engineered into a new mRNA vaccine extremely quickly. The important thing is that in order to contain this virus we do exactly what we’ve been doing already – isolating, masking, and continuing our vaccine program.