Nick Bennett MD

Pediatric Infectious Disease physician, with over 20 years of experience in research, academia, and clinical trials. Available for consultations in the areas of infectious diseases and clinical trials. Opinions are my own and not those of my employer or clients.

Should I get the COVID vaccine?

Posted in Uncategorized on November 22, 2020

TL:DR – Yes.

*Tap tap* – is this thing still on? It’s been a while.

The recent slew of data coming out from Pfizer and Moderna about their respective COVID vaccines has prompted a LOT of discussion about their utility, safety, and efficacy. I’ve had friends and family hit me up for my opinion through social media, private messages, and phone calls, and the truth of the matter is there’s a 50% chance I’ve already got a vaccine, and if I haven’t the company is looking to provide it to those in the placebo arm. Yes, I’m in a COVID vaccine clinical trial – the science and need is compelling.

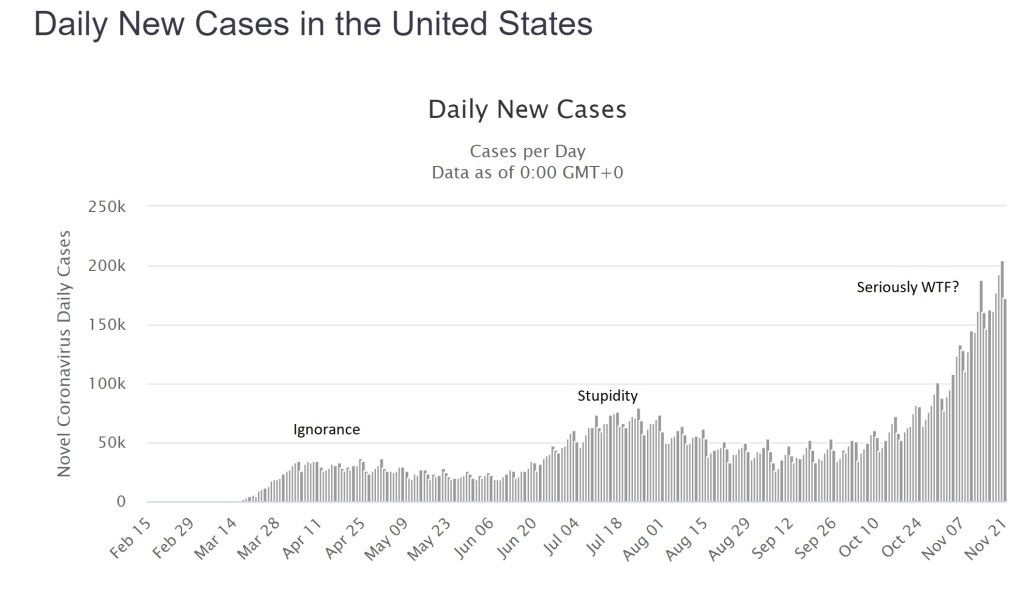

The global cases of COVID continue to climb with over 58 million worldwide as of today, of which about 12.5 million are in the US. Facing an accelerating “third wave” of cases of around 200,000 new reports and 2,000 deaths from COVID every day, there is no end in sight. This isn’t a hoax, it isn’t a “plandemic” or some other bizarre conspiracy theory, and it didn’t go away after the election – what we are dealing with is a predictable novel infection, likely zoonotic, the effects of which have been made worse by a series of abject failures in public health and education. I’m not going to debate that – it’s a matter of fact. Trolls will have their comments happily deleted, because I don’t argue with people who are wrong.

Having failed miserably to prevent the spread of this infection through such simple measures as staying home and covering faces, we now appear to have little option but to have faith in a vaccine of some kind. Herd immunity will otherwise cost millions of lives and probably trillions of dollars in lost productivity and economic output. The “low” mortality of 2-3% for COVID-19 is not low at all (the risk of death from a car crash is half of one percent, yet no-one in their right mind would recommend deliberately crashing their car…), and in any case the long-term effects of the infection on peoples’ health is likely to impact society for years to come. The fastest, safest way to stop the virus is through vaccination.

There are two vaccine candidates that have made headlines recently, both with similar technologies and claims of effectiveness, so for the sake of simplicity I’m going to talk about them generically. It seems likely that one or both of them will be approved by the FDA.

The vaccines use a “new” technology called “messenger RNA” or “mRNA”. The concept of an mRNA vaccine is not in fact new, and they have been researched for years. mRNA is entirely natural – every cell in your body contains some – very simply it is used as a go-between (a messenger…) from the genes coded within your DNA to the ribosomes where proteins are made. mRNA has a very specific structure – a linear molecule consisting of a mixture of 4 different nucleotides (adenine, cytosine, guanine and uracil) with a cap and a tail to ensure that the code is translated correctly and that other bits of RNA aren’t used accidentally. After the mRNA molecule is translated it is simply degraded and the individual nucleotides are recycled.

In theory, and apparently in practice, the use of an mRNA molecule as a vaccine would have several advantages. Most vaccines can be divided into one of two types: killed (or subunit) and live-attenuated. mRNA vaccines manage to combine the positive aspects of BOTH kinds, but the negative aspects of NEITHER. Allow me to explain.

In a normal viral infection the virus has to invade the body and evade the immune response, then infect a host cell. Viruses cannot replicate without a host cell, but in many instances the virus infection damages the cell function such that the host is affected and becomes sick. A virus that successfully infects a cell can take over the cellular functions, produce viral mRNA molecules, and force the cell to produce viral proteins. Cells though have several lines of defense, from producing chemicals called “interferons” that combat viral infection, to presenting viral antigens on their surface to the immune system (specifically, CD8+ T lymphocytes). Whether through the “innate” immune response like interferons, or through the “adaptive” immune response like T cells, nearly all of the time the host is able to successfully contain and clear a viral infection.

With a live-attenuated vaccine the goal is to mimic the natural infection, but without putting the host at risk of getting sick. The vaccine is usually made in such a way that the virus is defective and some aspect of its life-cycle is damaged – this means that the virus will still infect a cell and will still present its proteins to the host T cells, but the host simply won’t get as sick as they would with a wild-type infection. The result is often a VERY effective immune response that can last a lifetime after a single dose of vaccine, although sometimes boosters are given a few years later. Examples are measles, mumps, rubella, yellow fever, and oral polio vaccine.

Killed vaccines on the other hand use only “bits” of the virus, usually proteins that make up the capsid or outer membranes that are targets of the host immune response in natural infection. The hope is that by showing the host the purified proteins the immune system will produce a response that will recognize the virus should it try to infect the host in the future. The downside of these vaccines is that the type of immune response is slightly different, as the proteins are not presented from *inside* the cell. As such, the T cell responses are typically less, but instead there is a strong antibody response. Antibodies are very good at recognizing and neutralizing infections outside of cells, but of course since viruses replicate inside cells the real immunity actually depends on those CD8+ T cells. As such, killed vaccines often need multiple doses to be effective, and may not provide as much protection as the live vaccines would. Their advantage though is safety – there is literally no way for a killed vaccine to give the host an infection, whereas live-attenuated vaccines CAN cause disease if the host has an immune deficiency or if the virus mutates.

Looking now at mRNA vaccines it would seem as if they have the benefits of live-attenuated (internal protein production and presentation to T cells) AND the benefits of killed vaccines (no risk of causing infection in the host). In addition, despite the conspiracy theories you may read about online, there is no risk that the vaccine “becomes part of you” since there isn’t a mechanism for it to do so. Furthermore, a COVID-19 mRNA vaccine is an even better deal. The virus that causes COVID-19 has two very problematic aspects to it – firstly, it directly and significantly decreases that innate interferon response that is intended to stop the virus becoming established. This is likely because it evolved in bats, which have inherently high levels of interferon. In a human host, this virus is able to suppress our immune system very effectively, so that an otherwise mild infection is far more serious. Secondly, the adaptive immune responses (especially the T cell responses) in patients with COVID are also suppressed. Very early on it was obvious that the sickest patients with COVID had low number of lymphocytes, and over time we have come to realize that this also led to decreased adaptive immune responses against the virus. It seems that without the normal early response to infection, the host immune system is led awry, causing a dramatic, abnormal immune response that misses the target entirely and leads to the characteristic lung inflammation that has become a hallmark of the infection. What this means in practical terms, is that people who suffer wild-type infection often don’t mount great immune responses to the virus (reviewed here), and those responses seem to drop away with time. In other words, there may not ever be a population of truly immune people from this infection.

The only way to get immunity may be through an effective vaccine.

Both of the mRNA vaccine candidates, and other vaccines in development, have already worked to address this concern by demonstrating not only the typical antibody responses measured in most vaccine trials, but also effective T cell responses. This means that, on paper at least, we already have some reassurance that the immune response to this vaccine approach is meaningful and robust. In recent days, we have also learned that there is evidence of real-world protection for those who received the vaccine.

Both vaccine manufacturers have claimed around 95% “vaccine efficacy” from their vaccines. Now, this term has led to a lot of confusion, even among physicians, about what it really means. It does NOT mean that 95% of the subjects were protected. It also doesn’t mean that 95% of the subjects didn’t get the infection. It means that the risk of getting the infection was REDUCED by 95% compared to those who didn’t get the vaccine.

In real terms, the Pfizer numbers are a good example. Among the unvaccinated group, during the timeframe of followup (a minimum of 2 months) 162 patients were diagnosed with COVID. Among the group of vaccinated individuals over the same timeframe, there were only 8 infections.

The groups were randomized 1 to 1, meaning that approximately equal numbers of subjects should be in each group, and because the vaccine was randomly assigned the mix of ages, male/female, exposure risks etc ought to also be approximately equal between the two groups. So…one would also have expected around 162 infections in the vaccinated group, if the vaccine was not effective. Having only 8 infections is a huge decrease, which is where the “95% vaccine effectiveness” comes from.

What are the real world implications? There were over 43,000 patients enrolled, so approximately 21,500 would be in each group. 162/21500 is a rough guess of 0.75% of the population getting infected (although of course those people were enrolled over several months of time so the math is only a crude calculation). Those numbers mean that even without a vaccine, 99.25% of the placebo group didn’t catch COVID! I have heard arguments that the type of people who would enroll in a clinical trial like this may be more likely to wear masks and practice social distancing, which may be true, but if anything this would make it harder to detect a difference between the two groups, not easier – and the calculation of vaccine effectiveness doesn’t rely on knowing that. Nationally over the summer the average number of new cases in the US was about 50,000 a day. Over two months (approximately the average length of followup for the study participants, and the minimum required for safety data) that works out to 300,000, or about 0.9% of the total US population. This number is reassuring for two reasons – firstly it fits with the theory that the study participants were perhaps at a slightly lower risk of catching COVID compared to the national average, BUT the difference isn’t so great that it immediately calls the results into question. If the national rate was more like 10% and the study placebo rate was the 0.75% observed, it would look very suspicious. In theory, if the US population had been immunized over the summer instead of 50,000 cases a day, we would have had only 2,500 cases a day.

In addition, the safety data look great – significant fatigue and headache in 2-3% of the Pfizer participants after the second dose (I couldn’t find good data on the larger Moderna study, but the dose used in the Phase III study appeared to be well tolerated in earlier Phase II work). Now, admittedly we don’t have long term followup for several years because these vaccines are new, but intuitively and biologically we shouldn’t really expect any nasty surprises based on how the vaccine works in the body. One concern raised by some scientists and physicians is the possibility that the vaccine will induce an immune response that will make future infections worse – honestly, if that were the case we would have seen it in these clinical trial results. Among the “severe” COVID infections, in the Moderna study 0 of 11 cases were in the vaccinated group, and in the Pfizer study only 1 of 10.

So what do we have overall? We have a vaccine technology that induces biologically relevant immune responses that should be better than those of the real infection, with minimal risk. We have two clinical trials demonstrating dramatic differences between the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups that support highly protective vaccines. We have at best blunting of the epidemic from social distancing and masking, and an abject failure at containing it. Honestly, getting a COVID vaccine ought to be a no-brainer – it’s literally our last, best hope of getting back to something like normal, and it’s going to save millions of lives.

At the time of writing Dr Bennett has no financial conflicts of interest in any COVID vaccine product or company. He is a participant in a COVID vaccine study. Several of his friends have caught COVID (one was hospitalized), along with two non-immediate family members. Wear a damn mask.

Something old, something new…

Posted in Infections, Public Health, Vaccines, viruses on May 13, 2014

Unless you’ve been living under a rock (and even if you have) you can’t help but have noticed the headlines about all the viruses we’re seeing lately. Measles in Ohio – the largest outbreak in the US since 1996. Polio in Syria and Iraq – a resurgence of a once eradicated virus as war leads to a breakdown in the vaccination efforts. MERS – a second case reported in the US of a “new” zoonotic infection from the Middle-East.

There was a whole session devoted to these “emerging” infections at the recent Pediatric Academic Societies meeting in Vancouver. There are many lessons that we can take away from these events. Firstly, that the well-fought victories we have won against vaccine-preventable infections are actually more of a fragile truce. Given enough of a susceptible population many of these viruses are ready to recur. Measles is an obvious example: probably the most infectious disease known to man, and a plane ride away from ongoing outbreaks in Europe and Africa. One of the most embarrassing exports from my homeland of England has to be the disgraced Andrew Wakefield (I won’t do him the honor of calling him a “doctor”) who pedaled fabricated data to support his efforts to sell a “safe” measles vaccine to a fearful British public. But what about polio? For the first time in years we have seen a significant increase in cases worldwide, as the safety of those administering the vaccinations has been threatened by war. Even as India can now claim itself Polio-free for the first time, I’m starting to wonder if and when we might expect our first case of imported polio to the US from the northern African countries or the Middle East, as the vaccine delayers and refusers leave us with an increasingly vulnerable population.

Secondly, that the pathogens just keep on coming! The Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome virus is a coronavirus, only the sixth known to infect humans. It is entirely distinct from the SARS coronavirus, and we’re still trying to piece together exactly how humans are catching and spreading it. Thankfully human-to-human transmission seems to be inefficient, which is just as well as asymptomatic infection seems to be rare, and the mortality rate is about 40%! It’s just as well it has absolutely nothing in common with a virus that causes the common cold that could mean its transmission might become easier…oh, wait….never mind….

The third lesson I took away from the PAS meeting was just how adept we have become at chasing these infections down. Modern sequencing technologies allow us to send patient specimens from an outbreak of an unknown infection, and within a few days we can have a full-length genome sequence and a phylogenetic tree of its nearest and dearest. MERS was isolated in good old fashioned virus culture by a doctor in Saudi Arabia, then confirmed through collaborative efforts in the UK and Netherlands, and reported publicly through global mailing lists prior to publication. Infectious Disease doctors and epidemiologists are recognizing the ease of global spread of infection, especially novel infections, and the need to work together if we are to stay ahead of them.

But it’s not just exotic imports we have to worry about. The epidemiology of infections in the Americas is changing too. Florida has already become a place where Dengue fever can be picked up without the need for a passport, and as our climate changes that may change too. I saw three cases of imported Dengue in Connecticut last year, and all we need is the Aedes aegypti mosquito to set up shop here and our imported cases can become local! (Chronic Dengue in Connecticut, anyone?)

Just about the only positive thing to come out all of this, is that it’s pretty much guaranteed that my job will stay interesting for years to come.

What do I do exactly…?

Posted in Bacteria, EBM, Guidelines on November 3, 2013

I saw a very disheartening quote in a patient chart recently:

“…consider curbsiding ID for antibiotic recommendations…” Followed a few pages later by “Follow ID recs…”

It was disheartening in several ways: firstly that although someone had obviously thought us worthy of asking for advice they hadn’t actually called me about the patient; and secondly that they thought this question was worthy only of a “curbside”.

Regular readers and followers will already know my thoughts on curbsides – but I didn’t really delineate what I actually do. I addition, what should I expect of a consult and what should a consulter expect of the consultant?

A consult is triggered, at least on the inpatient side, when a physician asks a question of a colleague in another speciality. Now this happens informally all the time – we live in a learning environment after all – but a question along the lines of “I have a patient…” generally means that there are healthcare decisions being made on a real patient, and these are the real issue.

Most of the time a consult requires a specific question – I have had colleagues in fact pause for thought and tell me “I’m not really sure what question I have for you…” and then not bother formally consulting. In my mind, it’s very simple – if you are concerned or uncertain enough to seek out a subspecialty colleague for advice on a specific patient, that by itself is valid grounds for a consult. I have done more than my share of consults for “please assist with antibiotic management or further workup”. It’s not failure or weakness, nor a waste of my time – it’s what I do and it’s in the best interests of the patient.

I do expect a somewhat valid reason – a specific question is ideal, but even if I’m asked about antibiotic treatment I will usually try to go beyond that and include alternative diagnoses, testing, followup recommendations etc. I also expect timeliness – a consult should be called early, both early in the disease course and early in the day! I prefer to avoid problems than have to dig people out of them. I also like time to go to the lab before seeing the patient…and recently I had to fish culture plates out of the trash in order to help a colleague with antibiotic recommendations. Had they waited another day we would have had to use unnecessary antibiotics to treat more broadly than we needed to. Calling a consult prior to knowing all the information is ideal – I can often get preliminary results faster than the lab will report them and add on additional workup days ahead of time.

When I get asked a “simple” question like what antibiotics are recommended I go through the following steps:

Initial shoot-from-the-hip thoughts – what info do we have so far? How sick is this kid, risk factors, early lab results and prelim microbiology workup. I will ask for CBC (with diff, always with diff), CRP and sometimes ESR, renal and hepatic function as appropriate. Urinalysis results, and CSF findings if an LP was done. Empiric bugs will depend on likely source of infection and likely site of infection – the two might be quite different! Then I ask what drugs the kid is on and line up the likely antimicrobial activity of those drugs against the likely bugs and see if there are holes in coverage. I do this last step mentally over the course of a few seconds (usually) but I do it every time. Typically when I do the same process with residents or students it’s a several-minute slog through the bug/drug matchup table. Just because it’s easy for me doesn’t make it worthless though, it just makes me efficient. If the kid is “safe” then I tell them to stay put, if not I suggest additional empiric coverage before I even see the patient.

Second stage – chart review. I read the chart. Yeah, I really try to read it. ER records, admission note, progress notes, operative notes and even resident signout notes… I will scroll through every lab in the computer even if I don’t transcribe every one into the chart. Every microbiology lab, positive, negative or pending is recorded. I personally looks at x rays, scans, even ultrasounds (although my ability to read those things is pretty near useless). I always review the scans myself and THEN read the radiology report. Sometimes I’ll go down to radiology and review it with the radiologist.

At this stage if there are questions or additional workup obviously needed I will call the lab or let the team know, and if I get the chance I will physically walk over to the lab to look at the cultures myself. What’s the value in that you might ask? Well more than once has an initial “gram positive” gram stain turned out to be a gram-negative bug, and in some cases a gram stain alone can, with the right eyes and expertise, result in a diagnosis all by itself. On the culture plates, bugs like proteus, klebsiella, strep viridans, listeria, E. coli and pseudomonas have a characteristic appearance (and smell!) that may jump start the management a day before the Microscan or Vitek machine gives you the formal identification. A visual peek at a urine plate reported out as “flora” might reveal a predominant organism that you can point to and ask to get worked up.

Lastly – the patient. Go to the bedside, lay on eyes and hands. Talk to the parents and patient and find out the little nuances in the story that others missed – the dog bite in a kid with fever, the recent dental visit in a kid with bacteremia, the rash in a mom that started the day after delivering her baby… Test hypotheses, confirm or refute suspicions.

Sometimes with all of this I rethink my initial plan – which only goes to show how unreliable the shoot-from-the-hip curbside is. I may back off from my broad empiric coverage, or I may rethink a diagnosis completely and expand both therapy and workup. It’s not unusual for me to be consulted on disease X and have to tell the team that it’s really disease Y all along. A curbside cannot possibly do that. Any result requires a conversation with residents, students, nurses and colleagues – all of it educational and a two-way process.

So if you add all this up, what does it mean? It usually means, at minimum, a level four inpatient consult. Consults come in five levels – short of a life-threatening condition this is about as high as you can realistically go.

Let that sink in for a bit. A simple question of “what antibiotic should I use?” is justifiably as difficult as a decision to do elective surgery. In fact, based purely on asking me to review the evidence running up to the decision, there’s enough work to bill at that level even if I say “you’re doing a fine job, I recommend no changes or further workup”.

Yes, Infectious Disease specialists do all sort of other cool stuff too – we diagnose rare diseases, can help with resistant organisms or diagnostic dilemmas – but fundamentally we’re trained in how to best manage all the routine stuff as well. That’s not to say we need to get called on every pneumonia, meningitis or urinary tract infection – but if you get stuck with a question or concern with any of these it’s ok to ask for help.

And if you’re going to ask for help, don’t, just don’t, assume it’s not worth anything. No-one would dare ask a surgeon to operate for free…why treat your ID colleagues any differently?

Moving on up

Posted in Career on September 3, 2013

Flashback: sitting with my mentors and Attendings as a new ID fellow. The division chief asks the question – “Where do you see yourself in 10 years?”

“Doing something like your job, ” I tell him.

He chuckles.

My boss, the Division Head for Infectious Diseases, has always had my career interests at heart. Several times during my first year here we talked about 5-year and 10-year plans for myself and the division. He would share difficulties, ideas, insights and experience – always with an implication that someday, maybe “all this could be yours”. As a junior faculty, fresh out of fellowship, it was somewhat flattering and dare I say intoxicating.

I remember the day, now nearly seven months ago, when he sat me down in his office. There had been unforeseen difficulties in the recruitment for the new Chair of Pediatrics. At the last minute the carefully crafted collaboration between hospital, university and State fell apart and with the existing Chair well on the way to his new role there was an upcoming void to be filled. Fingers pointed to my boss to act as Interim Chair – a role for which he was ideally suited, having been on the selection committee and knowing the needs of the role intimately, being a genuinely nice guy, and having buckets of respect from faculty and staff in the institution.

He was very frank – “That five-year plan? I need you to start next month.”

Despite being the most junior member of the Division (one other doc there in fact has been practicing medicine longer than I’ve been alive) I was, ironically, the one best suited to run the day-to-day business of medicine. I’m the only other full-time physician in ID, my colleagues all having responsibilities to other areas of academic medicine or simply working off-site most of the time. My office is located next to the clinic, next to the administrator, the nurses, and the office manager. I’m on service and in clinic more than any other ID Doc (again, the whole junior member thing). For minor issues and questions, people were already used to just popping in to run ideas by me. He assured me the role would mostly consist of organizing the faculty meetings, making sure everyone did what they were supposed to do and be where they were supposed to be. I saw it as a prime opportunity to test the waters, see what I could do, and get some experience. Expectations were a six-month temporary situation while the hospital worked on recruiting a new Chair, and I figured I didn’t have much to lose.

Within a week it was clear there was more to the role – I was handed a survey to complete, detailing expected 5-10 year staffing and office requirements, for a division that I was just getting to know in its current form. People came to me with personal issues within and between divisions, professional concerns, financial concerns. I suddenly had a budget to keep to and five (later eight) physicians to keep on track to meet it. We had a visit from the Joint Commission, and we were still in the middle of a rollout of our new EMR, for which our division was one of the very first areas to go live, and we were still not back up to predicted visit numbers. There were meetings – where I was not only privy to the inner workings of the hospital, but also expected to contribute meaningfully and bring new things back to the rest of my group, and make it happen. Organizing the other ID docs (a task best described as akin to herding cats) turned out to be the least of what I was doing.

The most surprising thing of all was just how readily everyone accepted me as the person to go to. I think it speaks a lot to the attitudes and spirit of the institution that at no point did anyone make me feel undermined or inadequate, and that was somehow very humbling. I think some of that was because there were already several other young physicians in leadership roles – our hospital is less than 20 years old, and much of the growth has come from people like myself.

I found myself going in earlier and coming home later – plans to work on my research goals and apply for funding were simply shelved as my time was sucked up by the administrative tasks needed to ensure that we could take care of our patients. But with all of this extra work (I later discovered they’d allocated me 4% of my time to do this – I laughed out loud on the conference call at that piece of news) I was genuinely enjoying myself. I’ve always been one to want to know how things worked and the inner, secret details of things. Here I was, handed all this on a plate – and more, being given freedom (a shocking amount of freedom I felt) to make changes as I saw fit. Initially reluctant to do much without checking in with The Boss first, I later reveled in the opportunity to take the division in new directions and start up new initiatives that hadn’t been on the cards. I felt my wings stretch.

So what has happened over the last six months? We became the division of Infectious Disease and Immunology, as we added two clinical immunologists to the team (a process admittedly envisioned and started long before I was on the scene), and then had to work on promoting the new services to community physicians and hospital faculty alike. We changed outpatient clinic scheduling policies and inpatient consult practices, improved billing patterns and brought the division back to year-on-year growth. We’ve been added to the State newborn screening program for SCID (severe combined immune deficiency) and accepted as a site for an antibiotic clinical trial. I started building a collaborative program to care for kids with velocardiofacial syndrome (a particular immune deficiency syndrome I’m extremely interested in). Along the way a myriad of tweaks, reminders and attempts at cat-herding have kept us on track for what has been a pretty successful year. I began to wonder what would happen if my boss stayed on in his interim role – what would that mean for me?

I look back at all this because last week marked the end of my tenure as Interim Medical Director for the division. The boss and I spoke on the phone (in-person meetings are horrifically difficult to schedule nowadays) about what we would do next. Cold hard facts and practicalities were brought up. I’m not even two years out from fellowship – running a division is really for an experienced academician, ideally one with research funding to take the division down a new path towards a fellowship program of its own. How could we attract new faculty – more experienced faculty, faculty with funding, when they would have to work under me? In contrast, my research background placed me ideally to start working on establishing a lab and getting some grant money in – it would take time but he would help me apply for funds and get lab space. He also recognized my teaching skills and rapport with the residents – perhaps I should focus on medical education and curriculum development?

I let him speak – I wasn’t sure if he was just letting a stream of consciousness flow or trying to convince me of something.

Eventually, after about 45 minutes, he stopped and asked the question, “So what do you want to do?”

I realized with sudden and utter clarity that I was at a crossroads. I was being given my future career choices, with the full support of the future clinical head of the hospital. In a weird flash-forward dream-sequence I saw myself in these roles, feeling them out, trying to experience what it would be like. What dreams could I fulfill, how long would it take for me to get there, what would I have to give up…? And then the obvious hit me.

I would miss this job. I’d never intended to find myself so soon in the position of having to lead and make decisions, interpret data and trends and make policy that would impact the working life of my colleagues and the care of our patients, but if I left it I could see myself learning about problems and *wanting* to intervene and take the reins, and there would be a part of me that would be empty after “stepping down” from doing it for these past few months. How would the other faculty feel about another change of leadership? Would they still come to me regardless?

So I drew a deep breath, and I told him what I wanted to do.

And here we are. The announcement has been made. My boss is now the Chair of Pediatrics, and my role as the Interim Medical Director of ID and Immunology….is no longer interim. We have much to do – we have to think about finding an academic Division Head, expanding faculty further, working again towards our goals of expanding research and building a fellowship program. The last six months have been a transitional period as the cards were shuffled and a new hand dealt out.

And I like to think it’s a pretty awesome hand.

Is it serious?

Posted in Medical Education, Patient-Centered Care on July 13, 2013

A couple of things happened this week that inspired me to write.

My little girl got an infection. Oh, the irony. She was quite cute about it though. It started out as a mosquito bite or something like that – it was itching her at any rate. Little tyke was trying to put steroid cream on it to stop the itching. It probably would have worked if she hadn’t picked up the toothpaste instead. (She’s only 4, by the way)

So a day or two later and she’s got a red, painful, spreading infection on the back of her foot and I’m cajoling her to take oral keflex (first generation cephalosporin, good for group A strep and staph). She’s got a fever, vomiting, diarrhea…and we start worrying whether it’s an antibiotic side effect or the infection. It quickly becomes clear though that it’s the infection as she keeps down more of the keflex and everything starts to heal up.

As we sat brushing the hair of her My Little Ponies a day or so later she asked me “how did the infection get in there?” I pointed out the little bug bite and explained that it was a hole in her skin that let the bacteria in. “Oh, ” she said, “that’s dangerous.” And she went back to playing.

But yes, yes it was. Untreated staph and strep infections land kids in the hospital all the time. So was this a benign minor bug bite, or did I manage to avert catastrophic sepsis in my offspring?

This morning, quite by chance, my mum called for a chat. She asked me what I was doing – I explained I had to go into work for a consult. “Oh dear, ” she said, “is it serious?”

I caught myself just before I laughed out loud and said “No, not really” when I remembered what happened to my daughter this week. Just what was a serious infection anyway? Doesn’t that depend on your point of view as much as the organism, site of infection, and antibiotic resistance pattern? What is, to me, a relatively routine consultation, is at it’s minimum a human being whose body has been invaded by a microorganism which is attacking and destroying it from the inside! This is someone’s child whose health is not just in jeopardy but whose health has already been compromised by the fact that there is an infection there.

There are social implications to an infection like that – the stress and discomfort of a hospitalization, time away from family, and time off from school and work. This is a Life Event that will never, ever, be forgotten. For just a second, imagine yourself or a family member suddenly admitted to hospital and requiring invasive procedures for an uncertain cause. For some of my readers, I know they don’t have to imagine!

So we as clinicians need to remind ourselves of this from time to time. We must be wary of being complacent in what we see and mindful of how it’s perceived to the patient and their family. If we are confident in what we’re dealing with it behoves us to explain to patients and families why we think the treatment will work and how we expect things to go. Just because it isn’t end-stage cancer doesn’t mean we should ignore the same rules of breaking bad news – explain with clarification, give yourself time, give them time, allow for questions, provide reassurance without false hope and set expectations…there’s a list somewhere. Don’t pooh-pooh “routine” questions, because for that person they’ve never had to ask them before. Don’t belittle their experiences – pain, anxiety, anger. They’re all justified, in the moment, to them.

So to answer my mum’s question, yes – it was a serious situation. But the kid’ll be fine.

Bacteria and the Borg – resistance is not Futile

Posted in Bacteria, Infections on March 16, 2013

If there’s one thing that all Sci Fi nerds should know, it’s the catchy catchphrase of the cybernetic hive mind of The Borg – “Resistance is Futile”. True aficionados will recall the battle for Earth after the defeat at Wolf 359, where Captain Picard, captured and now “Locutus of Borg” was used by the Federation to destroy the Borg cube and save the Earth, proving that resistance, after all, was not futile.

In the same vein, many people view treating bacteria resistant to antibiotics as a futile endeavor. But it’s not as simple as all that. In order to understand why, we have to break down what it really means when we label a bacterial isolate as “Sensitive”, “Resistant” or “Intermediate”.

The core principle of bacterial resistance is the MIC, or minimum inhibitory concentration. The MIC is the concentration of a drug that will inhibit growth of that bacteria in the lab, in the old days tested using doubling-dilutions of drug and seeing which test tube the bacteria first grew in. The MIC was the dilution above that level (so if bacteria grew at a dilution of 1:32 but not in 1:16, the MIC would be 1:16). You can then give that value in terms of milligrams of drug.

Now, here is the key point. When we state that a particular MIC corresponds to being “sensitive” we mean that for THAT BUG and THAT DRUG it will kill the organism in the BLOOD, assuming normal dosing.

MICs cannot be compared between bugs. And more importantly they can’t be compared between drugs! You should NOT pick your drug based purely on the MIC that the lab reports out. In fact, a good lab will not report out the MICs, but will instead simply interpret them for you to say sensitive, resistant or intermediate (a weird concept, where the MIC is neither high enough to be considered truly resistant, but not low enough to be truly sensitive either – a clue that it isn’t a black and white interpretation). Unless you’re an ID doc or a pharmacist and you know what you’re doing, you have no need to know the MIC at all. The choice of drug should be based usually on the class of drug, and the location and type of infection you’re dealing with. I’d rather use oxacillin to treat staph with an MIC of 2 than vancomycin for the same infection with an MIC of 1, and I’d certainly never use rifampin by itself despite a potential MIC of 0.03.

If the infection is in a different body location, especially somewhere like the spinal fluid or brain where the blood-brain barrier can prevent drugs from getting in, then the MIC doesn’t apply. If only 20% of your blood level of drug gets into the spinal fluid, knowing that your bacteria is “sensitive” to blood levels isn’t entirely reassuring. In fact, for some bacteria the lab will report out separate “meningitis” MIC levels to take this into account, and many drugs have “meningitic dosing” which is much higher that normal dosing (remember, sensitivity MIC refers to that bug, that drug, in the blood, using normal dosing). Some drugs don’t even get into the spinal fluid at all – you’d never use cefazolin to treat staph meningitis for example, although for almost every other type of infection it’s one of the best anti-staph drugs out there.

The opposite may be true for urinary infections, as many drugs are concentrated in the urine, so urine levels may be 10-100 times the blood level, and even “Resistant” organisms will be killed.

But when you’re faced with a nasty bloodstream infection, or a pneumonia, or cellulitis where the MIC is probably helpful enough, and it’s resistant, what can you do?

It can depend on the resistance mechanism. Streptococcus pneumoniae has an altered binding protein, so simply swamping the bug with excessive penicillins might be enough to work. Staphylococcus aureus has a beta-lactamase that will destroy basic penicillins, and adding a beta-lactamase inhibitor will defeat that mechanism, or moving to a higher class of drug like a cephalosporin (first generation, of course).

But what about tougher bugs with weird mutations, pumps that remove antibiotics from the bacteria or porin mutations that prevent the antibiotic from getting into the bug in the first place? Sometimes a higher dose by itself isn’t enough. With some of the beta-lactam drugs the important concept is “time above the MIC” rather than sheer dose of drug. If the MIC is 32 but you can get blood levels of 33 for 24 hours a day using a continuous infusion, that will be enough to kill the infection, even though using traditional dosing that would be considered resistant. Prolonged infusion is a halfway house to try to achieve the same end, and can also be used to extend the total exposure of the organism to the drug “area under the curve” of a graph of drug concentration over time. And you can also simply use higher doses, assuming the drug isn’t toxic enough to limit that approach.

Incidentally this is why vancomycin is a crappy drug – sure, it kills MRSA, but the limits between effective and toxic are quite narrow, and you can’t increase the dose much at all without dinging the kidneys.

Another approach is the use of multiple drugs at once, targeting different bacterial biologic mechanisms. Intuitively it makes sense – attack the cell wall AND protein synthesis, or DNA replication, and you ought to kill it off faster. Often this approach is not simply additive – there is synergy between the two drugs such that 1+1=4 when it comes to killing ability. Relatively inactive drugs like the aminoglycosides (gentamicin, tobramycin) or rifampin, can be very effective when paired with a beta-lactam or other cell-wall agent. I call them the SALT drugs. Synergistic Although Lousy Therapeutically. And you’d never eat salt by itself, always with something else….unless you’re a goat.

One very interesting report of lab work with an old drug called colistin and vancomycin showed that if you put the two together, vancomycin could be effective against bacteria that it would normally have no activity at all against. The colistin punched holes in the bacterial membrane that allowed the vancomycin in to act on the inner cell wall. (WARNING – lab report only, do not try with real patients….yet…).

So when we are faced with resistant organisms, it’s never truly a totally lost cause. There are always ways to try to optimize either the dose or the timing of doses to keep drug levels up, or combinations to try, or novel ideas. But there’s no guarantee of success, in the same way that even with sensitive bacteria there are still going to be treatment failures.

Ultimately we need new drugs, and new drug classes. If we have to go up the development chain to counter old resistance mechanisms, all we’re going to go is promote the evolution of new resistance mechanisms. Even the newest anti-MRSA 5th generation cephalosporins are modifications of penicillin, when all is said and done. We really haven’t come very far at all.

When it really is a virus

Posted in Bacteria, EBM, Infections on November 30, 2012

I joke that, as a Peds ID doc, it is my duty to say this at least once a day…

Ok, I may not literally be slapping people upside the head, but there are certainly times when I’m doing it in my mind. The situation is common enough – a patient, parent or doctor, faced with symptoms consistent with an infectious disease, considers using antibiotics to treat bacteria. After all, we know that bacteria kill people, right? But in many of these situations the patient really has a viral infection – and viruses aren’t affected by antibiotics. So at the very least we’re wasting money and drugs. Worst case scenario? We’re promoting drug-resistant bacteria, antibiotic allergies and side effects – that in some cases can be life-threatening.

But aren’t there clues to help us make the distinction? Real clinical signs and symptoms? Well, lets review a few.

White pus on the tonsils

Everyone is familiar with the feeling of an awful sore throat, and having a doctor peer down and having you say “Ahhhh…” What are they looking for. Probably something like this:

This is a classic appearance of “Strep Throat” – a bacterial infection that aside from being painful in its own right can go on to lead to serious complications, such as rheumatic heart disease, kidney disease, a form of arthritis and a weird neurologic disorder called “Sydenham’s Chorea”. Fortunately it has no drug resistance so simple penicillin/amoxicillin will kill it (so if your doc tries to give you “stronger” antibiotics please feel free to slap them).

The trouble is, this isn’t a picture of strep throat. I grabbed this from an article on “Mono”. Infectious Mononucleosis can be indistinguishable from strep throat, but antibiotics do nothing for it. The “pus” you see isn’t really pus, it’s just a nasty-looking white gunk your tonsils make. A bad sore throat can be caused by influenza, adenovirus, RSV, metapneumovirus, rhinovirus….you get the idea. It can be hard to tell strep throat from any of the other many possibilities, but in general if you DON’T have a runny nose or a cough, and the lymph nodes in your neck hurt then it’s PROBABLY strep. But it could be a virus. Strep tests and cultures help – and holding off on treatment until the test comes back is a sensible plan.

Red eardrums

What about ear infections? Another common bane of pediatrics (almost every young child I see with a prolonged illness has at some point been diagnosed with an “ear infection” before arriving at the correct diagnosis – I once saw a kid with a brain tumor get that diagnosis…). The symptoms are notoriously non-specific (ear pulling, fussiness, fever) and a good ear exam in a small, squirming child can be difficult! A crying baby can turn their ear drums pink…and voila! An ear infection! But even assuming your exam is good and the ear drum really does look nasty, how do we know its a bacterial infection? Despite the appearance of a rip-roaring otitis media (bright red, bulging ear drum, fluid behind it) it can be a viral infection too. Most of what you see is the BODY’S response to the infection remember. Clinical trials of antibiotic use have shown with without antibiotics, ear infections tend to get better just as quickly as with them. Complications from untreated bacterial infections do exist, and can be quite serious, but are rare. It is prudent to consider a “wait and see” approach to ear infections to see if it gets better by itself. I don’t want your kid to get mastoiditis any more than you do, but if it does happen I want it to be treatable with the best antibiotics!

Most of the time when we’re treating ear infections we’re not even treating the child…we’re allowing the adults in the house to get a good nights sleep…;-)

Cough, fever, patches on chest x-ray

Pneumonia? Guess what. Usually a virus, at least in kids, before they become immune to everything. Without proper testing though this can be harder to tell apart, and we’re getting into the realm of “sick kid” here. Almost every doc will feel a little weird ignoring a possible bacterial pneumonia, even if they really do think its viral. But the high rate of viral infections, along with the risk of increasing drug resistance, is why the current recommendations for antibiotic treatment of pneumonia in children start with plain old amoxicillin. RSV, metapneumovirus, influenza, adenovirus – they can all cause pneumonia. In the Bad Old Days viruses like measles and varicella could also do it, and they were quite nasty! With symptoms like a runny nose, rash, lots of sick contacts, the chances of it being a viral infection are quite high. Sitting it out for a few days is again a reasonable option – because you know if you see a doc and get a chest x ray they’ll start you on antibiotics, and we don’t want that, right?

Very high fevers, difficulty breathing, chest pain with pneumonia, coughing up junk – always worth getting checked out.

Green snot

All of us have at some point experienced symptoms of a sinus infection. Fever, pressure, tons of snot, headache. They are truly miserable things. I hear all the time how “we knew it was bacterial because he had green snot”. Sorry, but that’s not all that helpful. The greenness of snot comes from the cells your body is sending in to kill the infection, which will tend to be neutrophils whether it’s a virus or bacteria. (Neutrophils don’t really kill viruses, but they’re just reacting to the inflammation there). Neutrophils have the awesome ability to create highly-reactive chemicals, one of which is called “superoxide” which gets converted to hydrogen peroxide which then reacts with chloride ions in salt to produce….bleach. The green color you see is actually the neutrophils and the enzyme they are using to create the bleach (myeloperoxidase), not the infection itself. You’ll get green snot regardless of what’s causing the infection, and it’s a good sign – a sign that your immune system is in full swing.

Severe sinusitis will produce lots of snot, for sure, but lots of snot doesn’t necessarily mean its a severe sinusitis, and certainly doesn’t prove it’s bacterial. If symptoms have lasted for a couple of weeks with no improvement, that’s a red flag for something non-viral.

High Fever

Fever is a normal immune response which effectively suppresses bacterial and viral infections. It hurts them far more than it hurts the patient. A fever by itself won’t necessarily cause any harm at all – and high fever may or may not indicate bacterial infection. A fever is just a clue – a reason to look and figure out what’s going on. One you’ve figure out it’s a virus based on symptoms (runny nose, viral rash etc) then you’re good. And don’t worry if fever keeps coming back, it will do that until the infection is gone, which may take a week or more.

The height of the fever is only slightly predictive of the risk of bacterial infection – but influenza, adenovirus, EBV can all cause pretty good-going fevers of 102F and up. I’m far more interested in what ELSE is going on in addition to the fever.

Febrile seizures, convulsions caused by fevers in young children, are more closely associated with a rapidly rising fever than a high fever itself. If your child has a fever of 104.5F and has sat there for an hour, chances are good they’re not going to seize from that.

Addendum – Mark Crislip recently posted on fevers over at Science Based Medicine!

Summary

So that’s a rough overview of the various common viral infections. It really is surprising how often we do get sick from something that will simply run its course. Our immune system is pretty robust. That’s not to say that in exceptional circumstances viruses can’t or shouldn’t be treated (herpes, influenza, chickenpox, measles, adenovirus, CMV and EBV all have some form of treatment to try even if the therapies are nowhere near as effective as antibiotics are on bacteria) but for respiratory infections in particular we would be far better served by reassurance that our symptoms are more consistent with a virus than a bacteria, and that most of the time it will sort itself out. A large chunk of the inappropriate usage of antibiotics stems from over-treatment of viral respiratory infections – so next time you see your doctor for something like this consider asking about tips for symptomatic relief rather than an antibiotic prescription.

A few other studies: prescribing antibiotics doesn’t necessarily save time.

Antibiotic overuse, even based on physician diagnosis, worse with criteria-based diagnosis.

Understanding why physicians overprescribe – many different reasons.

Good advice can be found on the CDC website.

I have been told that I must credit my wife for originally coming up with the idea for the “IT’S A VIRUS” slapping Batman meme, and Quickmeme helped me create it.

MRSA’s everywhere – ignore the MRSA

Posted in Bacteria, Infections, Public Health on November 16, 2012

Ermahgerd! It’s MIRZAH!

MRSA, affectionately pronounced “mur-sah”, and the abbreviation for “methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus”, has become the epidemic of our time.

Everyone thinks they know what it is. Few actually have a good handle on what it really means, especially with kids.

MRSA was first described back in good old Blighty in the 1960’s, not long after the drug methicillin was released in an attempt to combat the rise in penicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus. In the modern era methicillin is no longer available, due to kidney toxicities that are much less in the current selection of anti-staph penicillins (nafcillin and oxacillin), but the MRSA tag remains in use.

In practical, and literal terms, it simply means that the organism in question is resistant to that particular antibiotic. Well, whoopdedoo. Lets just pick another. Except you can’t. The way in which staph becomes resistant to methicillin is through the production of an altered protein that renders the bug resistant to EVERY antibiotic in that entire FAMILY of antibiotics. Penicillin? Gone. Cephalosporins? Gone. Beta-lactamase inhibitors? Useless. Carbapenems? Fat chance.

So you go to another class – quinolones, aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, sulfonamides – but none of them are especially active against staph and…wait for it….MRSA is often resistant to these drugs too.

The first place in which MRSA was discovered was in healthcare settings – long-term care facilities and hospitals. The overuse and abuse of antibiotics selected for strains of bacteria that had acquired all sorts of resistance genes. In fact, the gene for hospital-acquired MRSA is a multi-segment behemoth that carries with it all sorts of additional genes, so the whole lot are inherited together. MRSA infections were associated with severe, invasive disease and death, usually in adults already weakened by other diseases. Due to delays in starting the right treatment, and being forced to use second-line, less effective drugs like vancomycin, MRSA infections add to hospital stays and healthcare costs. Like to the tune of $60,000 apiece.

Just as the world was getting used to dealing with MRSA in hospitals, we started hearing about it in the community. People were showing up with skin abscesses, boils and other infections that were, in about half of cases, growing out MRSA. Worse, they didn’t seem to have any link to the typical risk factors of diabetes, renal failure, cancer, prolonged hospital stay etc. And even more scarily, this was being seen in kids.

But they’re different from the old hospital-acquired MRSA cases. The community MRSA gene cassette is far smaller, lacking the resistance genes of the hospital MRSA. We have a small, but reliable list of antibiotics to use to treat it. Invasive disease is unusual, skin infections are the norm. I have not, yet, seen a real hospital-acquired strain of MRSA in a child. I have seen a few kids pick up MRSA while in the hospital, but it’s always been the “community” strain brought in by visitors, family or other patients.

Diagram of MRSA gene cassettes – hospital (top, types I thru III) versus community (bottom, types IV thru VI)

Right now, I see a steady stream of kids with MRSA in my clinic and in the hospital. By far the vast majority are recurrent skin infections, often bouncing around various family members. Parents, reading up on MRSA online are understandably freaked out. Friends and relatives shun their kids, for fear of picking it up. Furnishings and furniture are steam-cleaned and thrown out, course after course of an antibiotic is given to treat each infection, but they never seem to go away. Even pets end up getting “swabbed” and tested in the lab, and yes, some are sent on their way as the presumed culprit.

None of this matters.

The truth of the matter is, while MRSA does indeed cause a good chunk of these kind of infections, it’s not got the hold on it. Just as many regular, sensitive staph (MSSA) cause these things. Fully one third of the population carries staph aureus on them – and clearly one third of the population is not suffering from recurrent skin infections. Carrying staph doesn’t mean you’ll get infections. And, annoyingly, you can test negative for staph from a swab (typically done from the nose) and still have infections elsewhere, such as the armpit, legs, or buttocks. We’re exposed to staph everywhere, all the time – and we mostly don’t even know it. That’s if we don’t have it already.

The reason why the skin infections keep happening is due to an entirely separate set of genes, related to immune evasion and skin invasion, which although more common in MRSA are also in some MSSA. (They are, interestingly, mostly absent in the hospital MRSA strains.) The way to get rid of it, if the levels are high enough for these infections to keep happening, is simply to decolonize the skin. That can be done with chlorhexidine washes and bactroban nasal ointment (a two week protocol), but you also have to prevent re-colonization, a more difficult proposition. Bathroom surfaces need to be bleached, towels washed daily (paper towels for hand washing) and EVERYONE in the household needs to have this done. There’s no point focusing on little Johnny with his butt abscesses if mommy and daddy, who are carriers, give him a hug and spread it back.

I never promise that with this approach staph will go away entirely. What we do know is that, if everything is done at once, you CAN eradicate staph at least temporarily from the skin. What we also know is that a third of the population carries staph….so wait long enough and you’ll get it again. I hope to merely reduce the frequency of outbreaks.

In my experience…this seems to work. Except in situations where kids have severe eczema or other skin issues, or where they’re not following EVERY step of the plan, I generally don’t see these kids back again.

So that’s prevention – what about cure? How should we treat these kinds of infections when they do show up? One drug that has seen a resurgence of late is bactrim – trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. A combination drug that is designed to inhibit the bacteria’s use of a chemical called folate which is a key component of DNA creation. It sounds good on paper, stop the bacteria from growing and it’ll die. In the lab, staph is often 99% sensitive or more (good odds when your risk of resistance to other staph drugs is around 50%!). The trouble is, in an abscess there is pus. And pus is basically dead and dying cells and bacteria. That’s a lot of DNA hanging around. Using bactrim in that setting is a lot like telling a farmer he can’t grow any more food, but putting him in a grocery store. He ain’t gonna starve any time soon. Bactrim also ignores the risk of strep, which are the other cause of skin infections and which are inherently resistant to bactrim. As such, deliberately targeting MRSA with this kind of approach actually results in MORE treatment failures than using a simple staph drug like cephalexin, even though that shouldn’t work with MRSA! You WILL get treatment failures with cephalexin too of course, and some with the other drugs like clindamycin, doxycycline etc. But it’s as if one should ignore the MRSA when planning your treatment. Drain abscesses (you usually don’t even need antibiotics if you do that) and then use a regular “skin infection” drug to minimize side effects and maximize your chances of success. These days we have NO ideal drug for empiric therapy of skin infections – but we certainly do worse if we panic about MRSA and try to tackle that first. Weird.

Of course sick patients are a different matter – even though the risk of severe invasive disease is low, the consequences are dire. You should ALWAYS cover a very sick patient with vancomycin or other MRSA drug until you know what you’re dealing with.

So I don’t panic about MRSA. I see it all the time. It’s annoying. It’s rarely dangerous. I know that if you focus on it to the detriment of the regular staph and strep you do worse. If someone is a carrier or has an active infection, good hand washing and covering any draining sites is enough to keep it at bay. No need to decontaminate entire schools just because a kid has been found to have MRSA. No need to put everyone on vancomycin if they’re not sick. And if they ARE sick, please don’t use vancomycin by itself, cos its a crappy drug and we only use it because we have to. Don’t bother swabbing just to check for carriage – positive results aren’t worth acting on unless the patient is sick (or, perhaps, due for surgery soon…that’s a whole other issue), and negative results are useless if the patient is actively infected. Deal with the infections, attempt decolonization, move on. Repeat if necessary.

MRSA – it’s a pain in the butt. And not just for the patients.

At the bleeding edge – the brave new world of EMRs

Posted in EMR, Patient-Centered Care on November 1, 2012

Today I had the privilege of being the very first doctor at my hospital to see a patient, document the visit (including a history and exam), write a note to the referring doctor, and complete my billing, using our new electronic medical record.

The build up to our new system has been over many months. Behind the scenes our IT dept has done its leg work, negotiations, analyses, and picked out what it hopes will be the best solution for us moving forward.

To be fair, we’ve had a semi-EMR already – a hodge-podge of software systems that barely talk to each other and seemed to have near-daily issues or crashes. My dictated visit notes were in one system, labs were in another, x rays in yet a third – and paper charts to top it off.

Not any more.

The new system will, eventually, replace all of this – and more. Our scheduling software is integrated, billing is integrated, all results are there alongside (indeed linked to) the visit they were ordered at, and every subspecialty will see what every other speciality does, including inpatient wards and the ER. Prescriptions will be faxed to pharmacies. Patients will be able to access their records online. It will be awesome.

There is, however, a learning curve. It’s not only a new software package after all, in many respects it’s an entirely new way of thinking and operating. For some Docs their work flow will be significantly altered, but it’s a fairly flexible system. It can handle point-and-click note creation, semi-structured “smart texts” which pull in data from the record, free-text typing, dictation – or even a mix of everything. As with most new roll-outs, our patient flow has been cut by 50% during the initial phase to cope with this learning curve. And I’ll freely admit that my first couple of appointments probably took about double the time I would have taken normally.

But let’s step back for a second. Really double the time? Really? What did I accomplish in that time? I completed my normal encounter (ignoring the computer except where necessary – I’m a patient-centered doc after all…) and then caught up with the software afterwards, transferring my scribbled notes into legible text and button toggles. I wrote my note. I wrote a prescription. I sent myself a reminder to call the family with the results of a lab test. I printed off a visit summary to give to the parents. Under the guidance of one of the “Super User” support staff I created a “new communication” to the kid’s pediatrician, linked my visit note, and faxed off a reply to the consultation. I selected a diagnosis and level of service, and with a click closed the encounter down.

I didn’t have to dictate a note.

I didn’t have to edit a note.

The pediatrician didn’t have to wait for me to dictate and edit a note – they had a copy of my recommendations at the office before the patient had left the building.

I didn’t have to flick through billing sheets, sign off on “problems lists” or “medication reconciliation logs”. I was all done with a click of a mouse.

It wasn’t extra time, it was reallocated time, time invested up front that saved me a ton of hassle later on. And as my learning curve moves up and I get faster at pulling down labs, creating smarttexts, macros and shortcuts this little beauty will truly save me time, AND provide better care for the patient.

Were there hiccups today? Of course, it’s a new system, but they had allocated sufficient personnel, expertise, resources and training into minimizing the problems and rapidly producing solutions.

A EMR is a tool – we still need our hands, our eyes, ears, stethoscopes and brains (and hearts…) to practice medicine effectively, but used properly something like this will only enhance what we can accomplish.

We entered a brave new world today, and I was the one to plant my feet in the sand before anyone else. It felt a little crunchy between the toes, but you know – I’ll have time to paddle in the surf later on.

Why I practice patient-centered care – and why you should too.

Posted in EBM, Medical Education, Patient-Centered Care on September 1, 2012

The simple reason why I practice patient-centered care is that it’s better for the patient. But before I go into the details of that, we need to step back a bit.

Firstly, I’ll clarify what patient-centered care isn’t. It isn’t pandering to a patient’s or parent’s wishes and doing whatever they want, as a mere provider of healthcare. That is patient-LED care. I don’t think that’s always a good idea – most people after all have NOT gone through medical school and several years of practical training (something like 20,000 hours of supervised patient-care in my case) in order to make informed decisions on their health. Even though the Internet has leveled the information playing field considerably, you still have to know how to interpret that information in the appropriate context and with the correct background knowledge. There are places where patient-led care does play a role, but it is quite distinct from patient-centered care.

I define patient-centered care as “practicing medicine taking into account the patient’s concerns, expectations and understanding.” You may not find that definition anywhere else put quite like that, but to me it makes sense. It also follows a three-step process of “discover, validate, address” that I iterate through an encounter so that by the end we’re all on the same page.

When I was in medical school I was lucky enough to be asked to pilot a new curriculum element called Preparing for Patients (my sole legacy to Cambridge University is that I was the first to coin the abbreviation PfP – which obviously was no great intellectual feat, but I think worthy of a footnote in the annals of history). I was not yet seeing patients on the wards, and felt quite unprepared having spent much of my work experience during high school in various labs – examining things like different plant species, fiber glass tensile strength and drug purity.

PfP was an intensive program back then, a couple of weeks of daily sessions where we explored our own fears and thoughts on medicine and patients, then got to experience and practice actually talking to patients about their illnesses. The real beauty was in the use of standardized patients: actors and actresses who could give a consistent experience to everyone and respond to questions, even off-line, in character. I got to tell someone they had cancer with a 50% mortality several times before I actually HAD to tell someone they had cancer (which as it happens was at 2am one morning on call as an intern, by myself – that’s deserving of a blog post all for itself…). The experience was invaluable, and provided a toolset of behaviors, questions and actions (71 skills all told) that I could bring into play when I needed them during an encounter. I got to try out this new-fangled curriculum and provide feedback to the course creators on the process and content.

The course itself still stands, albeit in a greatly modified form. It is now a fully integrated part of the Cambridge curriculum, from the first year of pre-clinical science, and those 71 skills are the benchmark by which all Family Medicine (aka General Practice) docs in the UK are assessed for their board exams.

What I learned from that was invaluable – it turns out that talking to patients is a lot more than simply asking questions about their symptoms. Patients are people – they have preconceived ideas about their illness, they have worries, they have ideas on what needs to be done. Sometimes they’re wrong, in which case our job is to educate and reassure (or sometimes not…), but often they’re right and our job is to help get things done. I learned that illness (what a patient experiences) is different from disease (what a doctor treats). A tension headache is an awful illness, but a minor disease that the doc can do little about beyond over the counter pain meds. High blood pressure on the other hand usually has no symptoms whatsoever but serious effects on the body so that we want to treat it. The question was posed – how do you convince someone to treat something that isn’t making them sick right now?

What I also learned was that there was actually research to back up this approach – patient complaints and concerns about medical care (including well over half of all malpractice lawsuits) usually stem from communication failures or unresolved issues. Issues often were unresolved because the doc either didn’t allow the patient to bring it up, or didn’t explain things fully. Patients do not tend to bring up what medics would consider the most important issues first – for all sorts of reasons – and yet they are often cut off early in the rush to get them out the door and see the next one. Something as simple as asking “What are you concerned about?” early on in the encounter can save a ton of time, as you can focus in on what they’re most worried about right away. (Of note, you’ll get different answers asking that than if you ask “what are you worried about?”, which I find fascinating…) Making someone feel at ease is one way to encourage them to talk about embarrassing symptoms or scary possibilities, and there’s an entire skillset devoted to building rapport and trust for precisely this reason.

My general approach is the “discover, validate, address” thing I mentioned earlier. Discovering concerns may be as simple as asking them what they are, but there may also be subtle hints – a family history of cancer, a perseverance on a particular topic or symptom, facial expressions and other body language. You may focus in on something you notice, or use open-ended questions to hear things in their own words. It may be an ongoing process through the encounter, but ideally you get most of it done early on to avoid the “by the way Doc…” question as you’re wrapping up.

Validation isn’t simply agreeing with them – after all, people often get misled or misunderstand things. Validation is acknowledging that from their perspective what they’re feeling about something is entirely appropriate. They may be angry that their prior Doc didn’t treat symptom XYZ, but if, medically, it didn’t need treatment, then their Doc did nothing wrong. But if I can commiserate with them, ask about how it’s affecting their daily life, explain that this kind of symptom isn’t one we can treat – this often goes a long way to fixing the issue.

Addressing a concern may be already covered by just acknowledging its existence, but may require an explanation of why treatment or testing isn’t necessary, or it may require convincing someone to undergo a treatment plan that they’re really not all that keen on! It’s important to offer options – there is always the *option of doing nothing*, even though that’s not necessarily the best option. It’s critical to explain YOUR thinking about something – admit your biases, your own concerns about the patient – they’re more likely to follow through on your recommendations if they know why you’re sending them for blood work, x rays or a cardiac stress test – or asking them to pop a pill every day for the rest of their lives!

What this approach does is help the patient have more control over their medical care than an old-school paternalistic approach, but with more education and understanding than a patient-led approach. If you train doctors to talk to patients this way an amazing thing happens – the patients do better. Improved communication can improve management of diabetes and blood pressure, but also reduce followup visits and tests, lower reported pain levels, and some surprising things like reduced costs in the ICU. Others have already listed the main references. To me this proves two things.

Firstly – there are clearly deficits with doctor-patient communication that need to be and CAN BE addressed.

Secondly – YOU CAN TEACH COMMUNICATION SKILLS. I cannot overemphasize this enough. One of the largest myths in medicine is that you either have a good ‘bedside manner’ or you do not, and if you don’t you’re stuck with it. That simply isn’t true. You CAN teach medics of all levels – from medical students to consultants – new skills and demonstrate changes not just in their behavior, but in their PATIENTS’ behaviors. This is an astonishing finding, and the skills can persist for years. The only thing more astonishing than this finding is that we’ve known about it for decades. Communication skills are being given greater emphasis in medical school these days, finally, but testing is haphazard and unhelpful a lot of the time (feedback 3 weeks after a standardized encounter is nowhere near as helpful as an immediate conversation and a chance to do-over the visit) and training is often limited to lectures rather than structured practice sessions. It is difficult to teach it properly, and it is certainly difficult in an area traditionally taught through lecture format, and which is increasingly moving towards online self-directed educational formats. Carving out a 1-2 hour block of time every week to sit down in small groups with a trained facilitator and one or two trained standardized patients is what’s probably necessary, but I doubt many course organizers think that they’re able to do that – my argument would be that we need to find a way to make it happen, not that we avoid trying because it’s difficult. I am living proof that you can take someone who honestly was pretty socially inept and turn them into someone who can not only practice patient-centered care, but teach it to others. Throughout my residency and fellowship I led a group of child-life specialists, Residents and Attendings in weekly sessions with the pediatric clerkship students teaching a modification of the Calgary Cambridge Guide.

One common criticism about teaching patient centered care or communication skills is that it somehow detracts from the teaching of “real” medicine – the mass of signs, symptoms, risk factors, tests and treatment options that we basically have to rote memorize, as well as the practical application of all that knowledge with real, sick patients. My counter to that is: who says the two are mutually exclusive? You can learn medical facts during the practice sessions, you don’t need to know them beforehand. You can integrate the two aspects of medicine – and in fact you probably need to integrate them or else risk maintaining the mental block between “real” medicine and “communication skills”. Real medicine relies on communication skills to elicit a history and convey a plan – how else do you think this can be achieved? Telepathy? Flash cards? Who says you can’t run a code in a simulation then afterwards have the “breaking bad news” simulation with the manikin’s “relatives”?

And finally, doctors that have a disease-focused approach are more likely to experience patients as “difficult”, and those patients are more likely to have additional (unnecessary?) visits, than if the doctor had a more patient-centered approach. Patient-centered docs are happier docs.

So, to me, effective communication skills are an absolutely integral aspect of patient-centered care, and patient-centered care is a way to dramatically improve patient outcomes. These skills can be taught, and I argue they should be taught if we truly want the best for our patients.

If any readers of this actually do rotate through ID with me, remind me to discuss the process of an encounter as much as the content…I tend to forget!