Archive for category Guidelines

21 CFR 312.60 General responsibilities of investigators (and more)

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Clinical Trials, Guidelines, Research on March 21, 2024

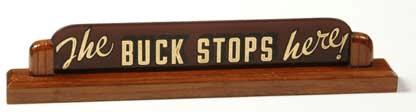

I chose this rather banal title firstly because it is descriptive, but secondly it draws attention to the seriousness of what it means to be an Investigator on a clinical trial. Following up from my first post on this topic, here I’m going to go into more detail on the role and responsibilities.

21 CFR 312.60 – An investigator is responsible for ensuring that an investigation is conducted according to the signed investigator statement, the investigational plan, and applicable regulations; for protecting the rights, safety, and welfare of subjects under the investigator’s care; and for the control of drugs under investigation. An investigator shall obtain the informed consent of each human subject to whom the drug is administered, in accordance with part 50 of this chapter. Additional specific responsibilities of clinical investigators are set forth in this part and in parts 50 and 56 of this chapter.

My first experiences as an Investigator actually stretch back to my earliest days in clinical research in 2004. I was in a kind of twilight zone for a little while, technically hired on as a study coordinator but, with my medical and PhD degrees, I was actually named and delegated responsibilities as a Sub-Investigator on several clinical trials. The training that we all have to do to undertake human subject research makes it very clear how serious and important the role of the Principal Investigator is. The preamble statement from the USA Federal law must be fully comprehended. “An Investigator is responsible for…” Do you really know what that means? If a study coordinator accesses medical records improperly for subject screening, the Investigator is responsible. If a nurse draws the wrong number of blood tests for a specific study visit, the Investigator is responsible. If a pharmacist dispenses the wrong dose of study drug for a subject, the Investigator is responsible. Investigators can (in fact, they must) delegate tasks to study site personnel who are properly trained and qualified to perform those tasks, but delegation does not absolve them of responsibility. This is a significant increase even from the supervisory role that many physicians are in, whether it’s teaching residents or fellows, or supervising Nurse Practitioners or Physician Assistants. As a Principal Investigator the Physician is held responsible even for tasks that they themselves might be incapable of doing (for example, study drug dispensing, or certain types of clinical testing).

This requires a seriousness of mind when a physician decides to undertake clinical research, and in addition it requires considerable support. Whenever I am asked about whether a physician should become an Investigator, my very first thought is “do they have enough support staff?” Having been a study coordinator, and having worked with study coordinators of my own, I have to say that regardless of how good a researcher might think they are, they will absolutely fail in running a clinical trial unless they have a good (if not great) study team. The administrative tasks associated with study start-up alone are Herculean – reviewing the Clinical Trial Agreement, Protocol, and Investigator’s Brochure, adapting the informed consent form (and in some cases, the protocol itself!) to local standards for IRB submission, completing the IRB submission (and any other review boards required), negotiating a budget, organizing sub-Investigators and collaborators, and ensuring adequate space and equipment exists to see subjects, perform procedures, and collect all the required specimens. All of that is before you even see a single subject. If you are able to get all that done, then a representative or two from the sponsor or contract research organization will visit to activate the site. A site initiation visit (SIV) is generally several hours of time for training, inspections, and administrative paperwork such as the delegation log, training logs, and FDA1572 “Statement of Investigator” form. Most physician Investigators are hard-pressed to even make it to an hour of the SIV – never mind attend the entire visit. I was fortunate to have excellent study staff to work with, and in fact a dedicated Clinical Trials Unit (with their own clinic space and lab) existed to help Investigators throughout the institution. My coordinators included a nurse, and I had a lab tech and study pharmacist team to use too. I was very well supported!

Aside from needing the appropriate mindset to conduct research seriously, and a solid team, there are several areas where Investigators can let their site down, even with the best intentions to heart. Perhaps the most frequent way in which Investigators can get into trouble is agreeing to perform a study that they cannot properly execute. When an investigator is initially approached for a study, they should perform a genuine, reality-based assessment of the feasibility of the protocol. If the blood tests require a -80C freezer, and they don’t have a -80C freezer, then they can’t agree to do the study until they buy one. If the study requires that subjects stay for 8 hours getting pharmacokinetic blood tests done, but their clinical trial unit closes at 4pm, then they can’t agree to do the study. If they only see 1 patient with that specific diagnosis every few months, then they shouldn’t commit to enroll 10 patients in a year. That last issue occurs again and again…I think in a (very) misguided approach to convince the sponsor to allow them to sign-up because they’ll be a “good site”. In truth this is a bad idea, for several reasons. Firstly, site budgets are often written based on the expectation that a certain number of subjects will enroll, and some overhead costs are averaged out over the entire patient mix. Obviously the specifics vary by institution and study budget, but I have certainly heard of sites getting into financial trouble because the investigators would consistently over-promise and under-deliver. Secondly, it makes the investigator look bad – because as much as they can promise the moon, when reality hits they can’t hide it. The CRO and Clin Ops teams will be pushing hard for enrollment, because they in turn are getting pushed by the sponsor for enrollment, and you can bet your bottom dollar that the sponsor is pushing because their Board of Directors and shareholders are pushing for enrollment! Do. Not. Over-promise. Thirdly, and this is a fun little factoid – but the average and typical enrollment data is publicly available. We can tell if a site looks like they’re over-promising, because their enrollment projections will be vastly different from those seen elsewhere in similar studies. I have absolutely seen research sites and Investigators removed from potential study site lists because they were not thought to be realistic.

Investigators can also negatively impact a study by managing their subjects too much like a treating physician. I have heard over and over again something like “Oh, yeah we identified 3 eligible subjects, but they’re not due back in clinic for 3 months.” What? No! So in 3 months you might talk to them about the study, you might give them the consent to review, and maybe they’ll bring it back and sign it in another 3 months? Talk to them over the phone, now, tell them there is a study they might be eligible for – give them any websites or other information (IRB-approved, of course), and you can even email them the consent to read over ahead of time. Bring them in EARLY for a screening visit, separate from their next official medical appointment, go over the consent in person and answer any questions, and if you’re lucky they’ll sign up next week! There is a sense of urgency in clinical trials that simply doesn’t exist in routine medical care. Do not wait to discuss research with your potentially eligible patients and families.

After enrollment, do not manage clinical trial visits and procedures as you would medical care – blood tests might be timed down to the nearest minute, study visits often have allowable windows of only a few days early or late (big tip to schedule study visits early in the window, in case anything happens and you have to delay). You have to be very well organized, and again this goes back to a diligent study staff team. For one clinical trial I was a coordinator on, I created a spreadsheet for all 191 subjects with built-in math to figure out all the required telephone calls and visits that had to be scheduled. A lot of studies these days have similar tools built into the electronic data capture systems to assist site staff with this, but I started back in the day of paper records for clinical trials… In any case, find a system that works and is reliable, and use it! The risks of a lack of diligence and organization are, at the least, protocol deviations and poor data. At the worst, the site can be shut down and the Investigator may be prohibited from conducting research. I have personally seen sites that were put on hold due to serious breaches in Good Clinical Practice (GCP – the rules regarding subject safety and clinical trial execution) that placed subjects at potential risk of harm, all due to a lack of diligence from the Investigator (remember “Clinical” in this context refers to medical research and clinical trials, not standard medical care).

Every Investigator should have undertaken training in the principles of GCP, in fact it is one thing that is repeated for every clinical trial training regardless of whether or not an Investigator has done it before! This training is not entertaining – it is snooze-worthy – but it is very important. The physicians who don’t pay attention to it are the very same ones who are immediately asking for permission for protocol deviations or to skip certain study procedures or visits “because they’re not needed”. If it’s in the protocol, it’s needed. I absolutely urge Investigators, whether would-be, newbie, or seasoned veterans, to pay attention when it is being done. Clinical research certainly isn’t something that should be done in a haphazard or half-hearted way. There is also no room for ego – Investigators and other study staff will make mistakes, Protocol Deviations will occur, misunderstandings will happen. The extremely high standards and rigorous oversight that are required for clinical trials is something that most physicians aren’t used to in their day-to-day practice of medicine, and it can often be misinterpreted as a personal attack or insult to their intelligence. The fact is, we’re really all on the same page, trying to get the best possible data, and keep the subjects as safe as possible.

On that note, the Investigators are responsible for the safety of their subjects. In that regard the opinions and actions of the Investigator matter a great deal. If an Investigator deems that a subject should be withdrawn from a study, they can do that. If an Investigator grades a particular adverse event as mild, moderate, or severe, then we generally rely on their assessment as the clinician who saw the subject (there are exceptions for specific laboratory results or protocol-defined criteria). Investigators assess whether an adverse event is related to the study drug or not. While the Medical Monitor and sponsor can (and often do) request clarification or confirmation of a specific finding, and sometimes even disagree with the Investigator, the Investigator’s assessments are still reported and are incredibly important. Some types of adverse event require very rapid (7 day) reporting to regulatory agencies, and that all hinges on the Investigator’s assessments. It is not unusual for Investigators to reach out to Medical Monitors for clarification or advice, but the Medical Monitors cannot provide patient care and cannot really direct an Investigator to do one thing or another. We can provide information and clarity on the protocol, insight into what the sponsor might think on a particular decision, and discuss any potential protocol deviations that might occur, but ultimately it is the Investigator that makes the final call. I have completed many telephone conversations with the line “I support your decision”.

In that regard I will discuss one final thing that Investigators do that causes issues, albeit rarely – subject unblinding. In randomized clinical trials, the subjects and often Investigators (even the Clin Ops teams and Medical Monitors) are all blinded and unaware of treatment assignment. This is so that no-one contaminates or biases the data from assumptions made of the treatment being given. However, it also happens that subjects occasionally get adverse events that may or may not be study-drug related. There is generally a clause in the protocol that allows for emergency unblinding under certain specific circumstances. That last bit is crucial – because unless it is genuinely thought that (a) the event is linked to the study drug and (b) knowing the treatment assignment will affect the medical management of the subject’s adverse event, there is no reason to unblind the subject! If on month 4 of a vaccine study the subject has a severe stroke, what would you possibly do differently with them, knowing what vaccine they got 4 months prior? Would you use a different brand of tPA? Would you shorten their rehab knowing that they “only” got placebo? No, it wouldn’t matter one iota. Trust me – the subject will be unblinded as part of the final analysis – and often studies have unblinded safety monitoring teams who will look at these type of events separately from everybody else on the study (I have sat on both blinded and unblinded safety monitoring committees for various clinical trials). There is very rarely any rush to unblind as an emergency, and if that is done it actually risks contaminating the data and losing that subject from the final analysis. By all means use emergency unblinding when necessary, but think clearly on whether or not it would actually change the management of the subject or whether it would “just be nice to know”. Do not risk the entire drug approval process just to appease your personal curiosity. It is perfectly reasonable to have a discussion with the Medical Monitor and the sponsor as to whether or not an unblinding should occur, and that can wait until the dust has settled and more information is at hand. Remember, an Investigator can withdraw a subject from a study at any time, and there are allowable reasons to stop study drug while still continuing in the study for safety follow-up. Neither of those options requires unblinding.

Those are highlights of the much broader and more nuanced role of a clinical trial Investigator than I can cover in a single blog post. What I hope I have imparted though, is a sense of how seriously the role should be taken. Investigators are literally the beating heart of clinical research, hugely important, with a great deal of trust given to them, and I found the role to be an incredibly rewarding aspect of medicine, both personally and professionally. I’ll cover how you actually become an Investigator in another post.

What do I do exactly…?

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Bacteria, EBM, Guidelines on November 3, 2013

I saw a very disheartening quote in a patient chart recently:

“…consider curbsiding ID for antibiotic recommendations…” Followed a few pages later by “Follow ID recs…”

It was disheartening in several ways: firstly that although someone had obviously thought us worthy of asking for advice they hadn’t actually called me about the patient; and secondly that they thought this question was worthy only of a “curbside”.

Regular readers and followers will already know my thoughts on curbsides – but I didn’t really delineate what I actually do. I addition, what should I expect of a consult and what should a consulter expect of the consultant?

A consult is triggered, at least on the inpatient side, when a physician asks a question of a colleague in another speciality. Now this happens informally all the time – we live in a learning environment after all – but a question along the lines of “I have a patient…” generally means that there are healthcare decisions being made on a real patient, and these are the real issue.

Most of the time a consult requires a specific question – I have had colleagues in fact pause for thought and tell me “I’m not really sure what question I have for you…” and then not bother formally consulting. In my mind, it’s very simple – if you are concerned or uncertain enough to seek out a subspecialty colleague for advice on a specific patient, that by itself is valid grounds for a consult. I have done more than my share of consults for “please assist with antibiotic management or further workup”. It’s not failure or weakness, nor a waste of my time – it’s what I do and it’s in the best interests of the patient.

I do expect a somewhat valid reason – a specific question is ideal, but even if I’m asked about antibiotic treatment I will usually try to go beyond that and include alternative diagnoses, testing, followup recommendations etc. I also expect timeliness – a consult should be called early, both early in the disease course and early in the day! I prefer to avoid problems than have to dig people out of them. I also like time to go to the lab before seeing the patient…and recently I had to fish culture plates out of the trash in order to help a colleague with antibiotic recommendations. Had they waited another day we would have had to use unnecessary antibiotics to treat more broadly than we needed to. Calling a consult prior to knowing all the information is ideal – I can often get preliminary results faster than the lab will report them and add on additional workup days ahead of time.

When I get asked a “simple” question like what antibiotics are recommended I go through the following steps:

Initial shoot-from-the-hip thoughts – what info do we have so far? How sick is this kid, risk factors, early lab results and prelim microbiology workup. I will ask for CBC (with diff, always with diff), CRP and sometimes ESR, renal and hepatic function as appropriate. Urinalysis results, and CSF findings if an LP was done. Empiric bugs will depend on likely source of infection and likely site of infection – the two might be quite different! Then I ask what drugs the kid is on and line up the likely antimicrobial activity of those drugs against the likely bugs and see if there are holes in coverage. I do this last step mentally over the course of a few seconds (usually) but I do it every time. Typically when I do the same process with residents or students it’s a several-minute slog through the bug/drug matchup table. Just because it’s easy for me doesn’t make it worthless though, it just makes me efficient. If the kid is “safe” then I tell them to stay put, if not I suggest additional empiric coverage before I even see the patient.

Second stage – chart review. I read the chart. Yeah, I really try to read it. ER records, admission note, progress notes, operative notes and even resident signout notes… I will scroll through every lab in the computer even if I don’t transcribe every one into the chart. Every microbiology lab, positive, negative or pending is recorded. I personally looks at x rays, scans, even ultrasounds (although my ability to read those things is pretty near useless). I always review the scans myself and THEN read the radiology report. Sometimes I’ll go down to radiology and review it with the radiologist.

At this stage if there are questions or additional workup obviously needed I will call the lab or let the team know, and if I get the chance I will physically walk over to the lab to look at the cultures myself. What’s the value in that you might ask? Well more than once has an initial “gram positive” gram stain turned out to be a gram-negative bug, and in some cases a gram stain alone can, with the right eyes and expertise, result in a diagnosis all by itself. On the culture plates, bugs like proteus, klebsiella, strep viridans, listeria, E. coli and pseudomonas have a characteristic appearance (and smell!) that may jump start the management a day before the Microscan or Vitek machine gives you the formal identification. A visual peek at a urine plate reported out as “flora” might reveal a predominant organism that you can point to and ask to get worked up.

Lastly – the patient. Go to the bedside, lay on eyes and hands. Talk to the parents and patient and find out the little nuances in the story that others missed – the dog bite in a kid with fever, the recent dental visit in a kid with bacteremia, the rash in a mom that started the day after delivering her baby… Test hypotheses, confirm or refute suspicions.

Sometimes with all of this I rethink my initial plan – which only goes to show how unreliable the shoot-from-the-hip curbside is. I may back off from my broad empiric coverage, or I may rethink a diagnosis completely and expand both therapy and workup. It’s not unusual for me to be consulted on disease X and have to tell the team that it’s really disease Y all along. A curbside cannot possibly do that. Any result requires a conversation with residents, students, nurses and colleagues – all of it educational and a two-way process.

So if you add all this up, what does it mean? It usually means, at minimum, a level four inpatient consult. Consults come in five levels – short of a life-threatening condition this is about as high as you can realistically go.

Let that sink in for a bit. A simple question of “what antibiotic should I use?” is justifiably as difficult as a decision to do elective surgery. In fact, based purely on asking me to review the evidence running up to the decision, there’s enough work to bill at that level even if I say “you’re doing a fine job, I recommend no changes or further workup”.

Yes, Infectious Disease specialists do all sort of other cool stuff too – we diagnose rare diseases, can help with resistant organisms or diagnostic dilemmas – but fundamentally we’re trained in how to best manage all the routine stuff as well. That’s not to say we need to get called on every pneumonia, meningitis or urinary tract infection – but if you get stuck with a question or concern with any of these it’s ok to ask for help.

And if you’re going to ask for help, don’t, just don’t, assume it’s not worth anything. No-one would dare ask a surgeon to operate for free…why treat your ID colleagues any differently?

Counterintuition – why neonatal herpes turns logic on its head

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Children, Guidelines, Infections on August 9, 2012

“No maternal history of herpes”

When dealing with a newborn baby with a fever, those are words that strike fear into my heart.

Wait, what? You said no maternal history? Yep, that’s right.

Neonatal herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a topic that is full of counterintuitive statements, and far too much confusion. The wrong people get tested, the wrong people get treated, the wrong babies get worked up aggressively. When other docs diligently rattle off the “pertinent” aspects of the maternal history and clinical examination of the baby, in my mind I’m mostly saying “Don’t care, don’t care, don’t care….” before I interject and ask about test results that often haven’t been ordered.

Based purely on a numbers game, thanks to things like vaccination and Group B Strep prophylaxis, many early onset infections in newborns have been reduced. There is simply less infectious disease hanging around. But as a result, viral infections like neonatal herpes are proportionately becoming larger players – in some hospitals it is as common as bacterial meningitis. And neonatal HSV is a killer.

HSV comes in three distinct flavors – the least lethal is skin-eye-mucus membrane (SEM) disease. This is how many people expect to see herpes – a rash, typically vesicular (clear fluid-filled little blebs) and maybe some eye discharge or mouth sores. Most pediatricians, if they see something like this, appropriately freak out a little bit. SEM disease by itself isn’t too dangerous, and if treated properly is almost never fatal. Herpes is tricky though – in babies it can mimic other rashes, so you really do need a low threshold to consider it. ANY neonatal rash that doesn’t fit a normal neonatal rash (so know your neonatal rashes!) deserves a workup. There is nothing more sobering than to run a case of a neonatal rash by an ID doc and to have them tell you with complete sincerity that “You can save this baby’s life. Get them to an ER. Now.” Untreated SEM disease can progress to infection of the brain.

The most obvious presentation is disseminated disease – which weirdly enough can occur before SEM disease…first week of life or so. The kids are sick – really sick. They can be in shock, bleeding, in liver failure and struggling to breath as the virus overwhelms pretty much every organ system. The problem here is that even faced with this situation bacterial infection is considered immediately, and herpes can still be overlooked or thrown into the mix as an afterthought. Again, good neonatologists and pediatricians will be all over this from the start, having experienced their share of disasters in the past. Disseminated herpes is mostly fatal without treatment – and even with therapy about a third will still die, many of the survivors left with significant disabilities.

The last type of herpes infection is of the brain. Typically presenting later in the neonatal period (3-4 weeks of age, rarely later) herpes encephalitis of the newborn is devastating. Herpes causes a hemorrhagic encephalitis, meaning that it chews your neurons up into a bloody pulp. To a brain that has barely begun its developmental process, this is a disaster. Even if the baby survives they may be blind, deaf, paralyzed or have significant developmental delays.

From how I describe it above you might assume it would be easy to spot these kids. Well, it is – once it’s too late. The success of treating HSV depends to a large extent on how quickly you can start acyclovir – one of the few medicines we have that can treat viral infections (it’s pretty much only used for HSV). Acyclovir can shut down virus replication, but does nothing for those cells already infected. The difficulty with HSV lies in the nuances of the medical history.

Let’s try some armchair science for a bit. Would you, as a baby, rather get HSV from a mother who is having a recurrent outbreak of HSV, with low-levels of virus, and have her give you antibody protection through the placenta…or would you prefer to catch HSV from a mother who is having her FIRST outbreak (which may be without symptoms) with high-levels of virus and no antibody protection? Well, you may ask, how likely is that? The answer is Very. About 90% of all neonatal HSV cases come from mothers with no history of HSV. If your mom DOES have HSV and has a recurrent outbreak, the risk of transmission is about 5%. For a new case – its closer to 50%. Maternal history of HSV is relatively PROTECTIVE for the baby.

But the focus is on the mothers who test positive for HSV during pregnancy. They get put on valtrex (an oral version of acyclovir which is well absorbed), when it has not been shown to sufficiently reduce transmission. They may get a C-section, when that hasn’t been shown to help either (except maybe in the case of active lesions at the time of delivery…and even then it’s unreliable). The mothers who are HSV-negative are ignored, when they are those at highest risk of passing HSV to their babies. In an ideal world, their sexual partners should be tested and if THEY are positive THEY should be put on valtrex to reduce outbreaks and educated about the risks. But the fathers aren’t the patient….so nobody does that.

A big myth about HSV is that all babies with it look sick. Well, they do eventually – but to start with they look pretty normal. I have heard docs say that a baby looked “too good to tap” – meaning they didn’t perform a spinal tap to check for meningitis or HSV encephalitis. Or they don’t test sufficiently for HSV, or don’t start treatment with acyclovir while test results come back (these same babies are almost universally started on antibiotics for presumed bacterial infection). Published case series of proven HSV cases shown over and over again that babies with HSV present with relatively innocuous symptoms. “poor feeding” “fever” “sleepiness” before the more obvious symptoms of “shock” “seizure” or “respiratory distress”. Remember, by the time the baby is sick from HSV the damage has already been done, and you can only try to stop it from getting worse and hope the kid recovers. With bacterial infections we can kill them directly with antibiotics and the damage is usually secondary to the infection, and not because the bacteria are literally eating up your cells and blowing them apart as HSV does. Even with successful treatment, symptomatic HSV in babies has a slow recovery.

So how do you deal with this uncertainty? You can’t trust the mothers history, you can’t trust the baby’s physical examination or symptoms…what do you do?

My approach is to have a low threshold for suspecting HSV in neonates. ANY baby getting worked up for a possible bacterial infection needs to have a workup and empiric treatment for HSV as well. Babies with weird symptoms (especially rashes or neurologic symptoms) need to have HSV considered FIRST, before bacterial causes. HSV is not only potentially devastating – its treatable, and therefore the bad outcomes are preventable.

Fortunately the Committee of Infectious Diseases of the American Academy of Pediatrics has published recommendations – albeit in a rather inaccessible set of paragraphs. I can summarize them here though:

Spinal tap for HSV PCR of spinal fluid.

Liver enzyme testing for disseminated disease – chest x ray if respiratory symptoms.

Surface cultures from eye, mouth, rectum and any skin lesions.Start acyclovir – do not stop until all tests are negative.

Do ALL of this this for EVERY BABY with suspected HSV.

Repeat spinal tap on kids with positive CSF to ensure clearance after 21 days – continue therapy if still positive.

A big mistake I see people making is in testing the spinal fluid to “rule out HSV” but do not doing the rest of the workup. Spinal fluid testing for HSV no more rules out SEM or disseminated disease than a urine culture can diagnose meningitis. I have seen cases missed (or nearly missed) because someone didn’t do the whole thing. You NEED the liver enzyme testing to rule out disseminated disease, and it matters. Treatment for simple SEM is 14 days – treatment for disseminated or CSF disease is 21 days. I have seen a handful of kids with positive CSF tests but with totally normal looking spinal fluid (eg no white cells, normal protein levels etc).

The trouble is HSV, as bad as it is, isn’t all that common among the hundreds of kids you will see with suspected neonatal infection. And many of THEM will be obviously HSV. So many kids get a semi-workup and we get away with it because “whoops, the CSF is positive!” and you treat for 21 days even though you didn’t check the liver enzymes.

But I’ve also seen the opposite – kids who were partially worked up and the diagnosis was missed, or delayed, or the severity was under-appreciated. All too often the “standard of care” let’s these kids slip through the cracks – which is inexcusable in my mind when there are experts who put it down in writing exactly how to work up these cases.

So let’s raise the standard.

Totally useless history:

Mom has no history of HSV

Mom got Valtrex

Mom got a C-section

Baby looks well

REAL risk factors for neonatal HSV:

Prolonged rupture of membranes

Active lesions at time of delivery

NO maternal history of HSV

Prematurity

Age less than 21 days

Unusual rash

Seizures or lethargy

“Sepsis” not responding to antibiotics (oops! too late! – better call your lawyer…)

Testing

CSF PCR

PCR/Culture of skin lesions, eyes, mouth, rectum

Liver enzyme testing

Chest X ray (if symptomatic)

Treatment

Acyclovir 20mg/kg/dose IV every 8 hours

Until all tests are negative (typically 2-3 days empirically)

14 days for proven SEM disease

21 days for disseminated or CNS disease

And if you’re not sure…get a consult…

Learning your lines

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Bacteria, Guidelines, Infections on May 28, 2012

I was recently asked “what is a line infection?” and I realized that it would take more than 140 characters to explain everything about it. I also figured it would be a good topic to educate on, since as a whole line infections are very badly managed.

Briefly, a line infection refers to a bacterial (or fungal) infection of a central line, usually in a vein but an arterial line could get infected too. The classic case is a catheter tip infection with bacteria in the bloodstream. The patient may have a fever, and may be quite sick indeed.

One might ask; “How the heck does that happen??!!”. Actually, surprisingly easily.

Lines can be infected from two ends – the outside end is open to the air and is accessed every time a medication or IV nutrition is put through it. If sterile technique is not used bacteria can get into the line. Heck, even with sterile technique bad luck plays a part too. These bugs are often skin bacteria that are normally fairly wimpy or considered “contaminants” when grown in blood cultures (meaning they were picked up from the skin as the needle went in, not that the lab contaminated them!). The inner end is safely inside a blood vessel, which is sterile, but if bacteria get into the bloodstream for other reasons they can stick to the plastic line, since bacteria as a rule LURVE to stick to non-biologic stuff. These can be any kind of bug, but are more likely to be bacteria from the gut who wandered off accidentally in the bloodstream and find a home there before the immune system can kill them off.

Once a line infection is established, we have a problem. Plastic lines have no bloodstream and no immune system. Bacteria can produce slimely stuff (called a biofilm) that coats the infection and acts as a barrier to the immune system, and some antibiotics. Imagine smearing peanut butter on a table, then trying to get it off with your finger. Even after a good swipe you’ll leave a smear behind. Now imagine trying to clean it off by dripping detergent onto it. That’s what it’s like trying to clear a line of a line infection. The only way to guarantee clearing a line is to pull it out and put a new one in.

Pulling a line is not a lightly-undertaken job though. If someone has a line they probably have a reason for it – long-term nutrition, chemotherapy, antibiotics etc. If you pull that line you may interrupt their usual doses, for days at a time. Line sites get scarred and if you do this enough you can run out of new sites to use! So it’s paramount to diagnose a line infection properly.

Imagine the following: a kid with a line gets a fever. They come to the hospital and blood cultures are drawn from the line. They grow a staph aureus. OH NO! He has a staph aureus line infection right? Not necessarily. Blood drawn from the line is just blood – this could be any other staph bacterial bloodstream infection, such as from a bone or joint infection, endocarditis (infection in the heart) or something else. We need to know whether the line has more bacteria than the rest of the blood stream.

This is where most people go wrong – you MUST MUST MUST draw multiple cultures, including a culture from some place else (and yes, this means sticking a needle in someone – suck it up). Ideally you need quantitative cultures, where you draw a fixed volume of blood then plate it out and count the colonies. If the line cultures grow significantly more than the periphery, it’s a line infection. If it’s the same, it is a bacterial bloodstream infection, but not a line infection. BIG difference. If you can’t do “quants” you can time how long the cultures take to turn positive in the lab. Most experts consider a difference of a few hours to be significant.

Once you know it is a line infection, you can think about what you’re doing. Most people get started on broad-spectrum antibiotics to cover all the likely bacteria. Once you know your bug though, you can tailor therapy. Non-Aureus staph for example may actually be cleared using a couple of weeks of antibiotics. Enterococcus or staph aureus are tougher, gram-negative bacteria from the gut are even worse. Pseudomonas or candida/other fungi are practically impossible to clear, don’t even try.

What’s the harm in trying? Time. You waste time. You have a kid sitting in the hospital getting IV antibiotics. You may send them home…and you may be able to show that the blood cultures turn negative….but you stop those antibiotics and WHAM the peanut butter smear you didn’t quite clean off has grown back into a big old dollop of yuck again. You’ve wasted 2 weeks at least, several days of hospital time AND now you’re back at square one and you have to pull the line you should have pulled two weeks ago.

The two biggest errors I see people try with line infections are: not correctly testing for line infection with sufficient blood cultures; trying to salvage an unsalvageable line. People are fooled into thinking they have cleared a line infection, when in fact they may have been treating a bacteremia from another source and just THOUGHT they were treating a line infection. This reinforces the incorrect belief that clearing line infections is easy…

I get consulted on these kids. I can rarely offer specific guidance unless the correct workup has been done. I have seen kids get lines out that I am sure were not infected, and I have seen kids treated for weeks for an infection that could have been cured with a 30 minute procedure to pull the line out. There are evidenced-based guidelines on this issue published by the Infectious Disease Society of America – ID docs KNOW how to manage line infections – and yet our guidelines, and our specific advice, is often ignored.

Best reason I was ever given for not removing an infected line? “We can’t take it out, we’re using it for the dopamine”. Yeah, well maybe if you stopped using it the patient wouldn’t be in shock any more…

Screenshot of the most critical table from the IDSA guidelines.