Archive for category Nick Bennett MD

Science should dictate policy, not the other way around.

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Antivax, Nick Bennett MD, Public Health, Vaccines on July 2, 2024

It’s taken me a little while to put virtual pen to paper in response to the appalling report from Reuters that revealed how an official US-government-sanctioned campaign set out to deliberately undermine COVID vaccination efforts in the Philippines.

Through phony internet accounts meant to impersonate Filipinos, the military’s propaganda efforts morphed into an anti-vax campaign. Social media posts decried the quality of face masks, test kits and the first vaccine that would become available in the Philippines – China’s Sinovac inoculation.

Reuters

The program, which apparently ran from 2020 through the end of the Trump administration and months into 2021, was a deliberate act of propaganda to undermine the influence of China on the global COVID vaccine stage (which the USA was not contributing to at all at the time). While Americans were “not targeted” by the misinformation, that specifically set out to disparage and undermine the Sinovac vaccine that was in widespread use in that region at the time, there cannot be any doubt that the lives of locals were placed at risk. As an infectious disease specialist who has dealt with antivaccine misinformation for all of their professional career, this is simply unacceptable to me. Regardless of the relative merits of one vaccine over another, or the petty machinations of the political regimes, during a global pandemic it is an abject failure of humanity to deliberately place other human beings in harm’s way.

This isn’t the first time that vaccines have been used as tactical tools – in the hunt for Bin Laden the CIA used a hepatitis vaccine program to collect DNA from children in an attempt to discover links to the terrorist in hiding. When the ruse became public, vaccine workers (even those with nothing to do with the program) were targeted and the polio eradication campaign stalled, with effects that have taken over a decade to even start to undo.

In response to the Pentagon’s efforts to undermine China, Filipino vaccine rates were woefully low, to the extent that the Government had to threaten jail for those who refused vaccination. When the US was approaching herd immunity at 65% coverage, in June 2021 the Philippines had only about 2% of their population immunized.

It takes a special kind of heartless disregard for science, and the welfare of other human beings, to promote this kind of act and go along with it. I suppose should we expect anything less, coming from a political leader who downplayed the seriousness and very existence of the problem and then politicized masking and social distancing, even as they sent protective equipment to their political allies. After vaccines became widely available, the anti-science mindset among Republicans was responsible for a 43% higher rate of excess deaths compared to Democrats in Florida and Ohio.

Arguably, deliberately undermining vaccine programs for political gain is tantamount to poisoning a water supply, which is literally a war crime. I cannot overstate how upset I am about this entire story – we as the experts have a hard enough time educating a scared and skeptical public about the measures that we are recommending to literally save them from themselves, without having our work attacked and undone by the powers that be.

Study Coordinators – why they matter so much.

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Clinical Trials, Nick Bennett MD on May 31, 2024

One of the first things I tell someone when they ask me about doing clinical research is to make sure they have a good study team, and a good study team starts with a good study coordinator.

The role of a study coordinator (also called a clinical research coordinator or CRC) can be highly varied or very specialized, depending on the site and how they have their research organized. I have worked in both settings, and in fact I cut my clinical trial teeth 20 years ago in the role of a CRC where I was responsible for basically every task in the execution of the clinical trial. Think I’m kidding? Here’s a list off the top of my head…

- Re-wrote the industry protocol for IRB submission.

- Drafted/edited ICF for IRB submission.

- Completed the IRB submission, answered IRB questions.

- Created all source documents for the visits.

- Pre-screened patients.

- Met patients in clinic, consented, screened.

- Ensured study drug/vaccine orders were placed properly.

- Collected blood and urine specimens.

- Processed blood and urine specimens (centrifuge, aliquoting).

- Packaged and shipped specimens.

- Met subjects for follow-up visits in clinic.

- Dealt with queries from the clinical monitor.

- Made calls to the medical monitor.

- Completed CRFs.

- Met with clinical monitor for monitoring visits.

- Called subjects for telephone follow-up, tracked subject schedules.

- Called external offices for medical records.

- Completed/communicated SAE reports.

- Trained other study staff (and non-study staff) on the clinical trial.

Now, not every study coordinator can do all of those tasks, but as a Principal Investigator a lot of those are practically impossible tasks to fit into their existing schedule. For this reason a study team often consists of people with diverse skills and roles – for example a study nurse for procedures and assessments, and a data manager for CRF data entry and query responses. It should be clear though that a lot of the front-line work that’s required for running a study site requires having a reliable and smart person on the study team as the study-coordinator. Because clinical research is so tightly regulated, you can’t afford to have someone who isn’t careful and thorough on the team. You can also see the advantages of having experienced and well-trained individuals in that role, so it’s perhaps unfortunate that the role of CRC is one that is notorious for being relatively underpaid (compared to the tasks and responsibilities expected of them…) and for having high turnover (about twice the national average, at 30%) and COVID made this worse, with rates as high as 60% for some research sites in recent years.

The salary ranges for a CRC are as low as 37k/year, but can get up to a little over 80k. Many CRCs have medical backgrounds and they tend to be the ones paid at the higher end (for example, nurses, nurse practitioners, or even physicians who perhaps are new to the US and looking for a way to get started). Some of them though are wanting to get started on their careers, and the CRC role is really just seen as a stepping-stone. The turnover therefore isn’t because it’s a bad job (it’s actually a really fun job in my opinion!) but simply because being a CRC is not usually anybody’s career goal! People move on to the clinical monitoring role for a pharmaceutical company or CRO, or start their medical career training, or simply move up the ladder at their specific institution. The skillset and experience that is gained from working as a CRC are in demand all over the world of clinical research. The trouble with this turnover is that there are study-specific things to know, which might be due to the protocol, or the drug, or the sponsor, or the workflow at the specific institution, and losing study staff who have been trained up and who are SO crucial to the study execution means that the new CRC who picks up the mantle has to be trained all over again.

It’s very important therefore to properly mentor and support the CRCs at a site. If they are overwhelmed, mistakes are more likely. The already high rate of turnover will only be made worse, which will in turn impact the other CRCs and ongoing research at that site. I have been informed on several occasions that sites have slowed down enrollment, or even paused their research entirely, because of a staff shortage in the CRC role. It’s absolutely a worthwhile investment to have enough staff on the team to provide backup coverage and support where needed, and to have a succession plan in place for when a CRC moves on. Careful documentation of study-specific needs are crucial, as is effective and regular study team meetings with all the staff. Even if you’re not working on a particular protocol, you never know when you’ll be expected to do the work because someone is out sick, or starts their new CRO job.

As an Investigator or site manager, it would be important to bake in this salary support to things like budget negotiations with sponsors, or FTE requests and expectations with an institution, and to support ongoing training and education for the CRCs so they feel valued and can advance in their chosen career. It really is a great way to enter the area of clinical trials, whether investigator-initiated or sponsored studies and I have zero regrets from my time on the frontlines.

I could probably write a short post (maybe even a long one!) on any one of the tasks performed by a CRC in their day to day job, but for now I hope this brief insight is enough to make people realized how important they are.

Powassan virus – an “uptick” in cases, or simply better awareness?

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Nick Bennett MD, Public Health, Uncategorized, viruses on May 9, 2024

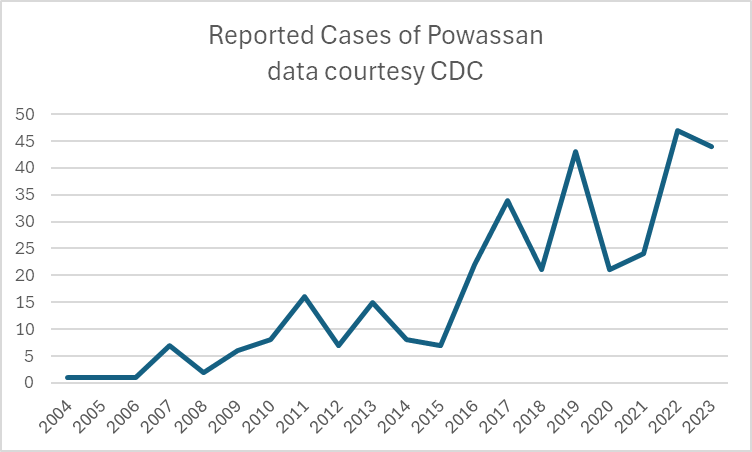

A recent headline caught my eye, discussing an increase in the annual reported cases of Powassan virus – a virus which (for reasons that will become obvious) is near and dear to me. I decided to take a look at the actual data in more detail, and discuss a bit of that here, because understanding viruses like Powassan has implications beyond just this one infection.

Let’s start with what Powassan virus really is – it’s an arbovirus, meaning transmitted by arthropods (in this case, Ixodes ticks), and has an ability to cause a form of encephalitis. It is in fact closely related to the Tick Borne Encephalitis (TBE) virus, but Powassan virus was actually named after the town in Ontario where it was first discovered. It’s highly likely that many (perhaps the majority) of infections don’t go on to cause very serious disease, but the actual risk of encephalitis from it is unknown because the total number of cases isn’t really known. Of the symptomatic cases, about half are quite serious and 10% are fatal. The CDC has made it a nationally reportable infection, but the tricky part is knowing when to even think about it…

I diagnosed the first ever case of Powassan in Connecticut in 2016. It really was a bit of a crazy story, and truly a perfect storm of being in the right place at the right time. A young infant boy was admitted to the ICU with seizures and a very clear story of a few hours of a tick being attached to his leg 2 weeks earlier. The tick was brought into the house on a family member’s clothing, and probably got onto the child during a feed while being held by this person. The medical team had quite correctly ruled out most tick-borne infections due to the very short attachment time, but I knew that there was one exception – at least in animal models, Powassan virus could be transmitted in as few as 15 minutes. So it was possible, but was it probable? The clincher was the MRI report, which had a very distinct pattern showing “restricted diffusion of the basal ganglia and rostral thalami, as well as the left pulvinar”. There was no sign of more widespread of diffuse signal changes as you might see with ADEM (acute disseminated encephalomyelitis) or cerebellar changes as you might see with enterovirus. No hemorrhagic changes, as with herpes simplex. The laterality and location of the damage matched the physical symptoms (motor dysfunction affecting the right more than left), but more importantly it was also similar to previous reported scans from patients with arthropod-borne flaviviruses, including Powassan. Choi and Taylor wrote in a 2012 case report “MRI images of the patient’s central nervous system (CNS) were unique, and when such images are encountered in the clinical setting, Powassan viral infection should be considered.” We were able to test the baby’s spinal fluid at the CDC for Powassan, and it came back positive.

The points to make about this case are several – firstly, the recurring comment from most (probably all) of my colleagues when I made the diagnosis was “What made you think of it?” Honestly, it was mostly the fact that I had training in a state where Powassan was well-known and we would consider it routinely. I simply added it to the differential and saw that not only could I not rule it out, I had some evidence to support it! But the issue here is that there were probably many cases of Powassan over the years that doctors had been seeing, but simply never thought of testing. Powassan was not on a routine viral encephalitis panel in Connecticut (it’s a send-out to the CDC), whereas some other State laboratories like New York test for it automatically on their own encephalitis panel, in addition to sending/reporting to the CDC. It is very much a case of out of sight, out of mind.

Secondly, even if some physicians had considered and tested for the virus somehow, Connecticut didn’t make Powassan a reportable disease until 2019 (more than 2 years after I made the first diagnosis in the state). It’s really hard to measure something if you’re not counting it…and of course even hard to count something if you’re not looking for it!

So this makes it really, really hard to know what to do with news that “Powassan cases are increasing.” Reports are increasing, but so is awareness, and testing availability – it doesn’t mean that actual infections with the virus are going up. It is possible that they are…but the case reports alone aren’t enough to make that conclusion. You really have to understand the reporting infrastructure and testing limitations in the context of a specific disease when trying to interpret the changes you might see in any sort of incidence or prevalence data.

There isn’t a vaccine yet for Powassan virus, although when I last checked research was ongoing (and there is a vaccine for TBE). The best way to prevent infection is to avoid any kind of tick exposure at all – cover skin, use DEET, avoid tramping through the wilderness in areas where the virus is known to be in ticks, and check your pets! Also – change your clothing when you get indoors from activities that might have exposed you to ticks…

Bonus if you’ve made it this far – you can check out my TV appearance on Monsters Inside Me below!