Archive for category Uncategorized

Garbage in, Garbage out: Does AI have a role in clinical research?

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Uncategorized on October 22, 2024

I’ve seen a lot of talk recently on the possible roles of AI in clinical research. I say “roles” plural, because really it’s not a simple case of whether or not AI will enter the clinical research arena (it already has to some extent), but really how best can AI be utilized to actually improve the process.

In theory, an AI could be used in many of the roles that are currently human. With certain limitations and caveats, AI has been shown to be fast and effective at producing written content or organizing data – both things that are vitally important in the design and reporting of clinical trials. AI models can also be trained to identify and track signals in safety data or find patterns in protocol deviations that might otherwise be too subtle to see. An AI might find an efficient CRA scheduling pattern for site visits to maximize on-site time and minimize travel, and a predictive model based on social media posts and web searches might predict the next location for an infectious disease outbreak so that local study sites can be brought online quickly.

But those limitations and caveats I mentioned above are the weak link in all things AI-related, and I do not for second think that we’re at the point where AI can be considered anything other than yet another tool to draw upon when performing clinical research.

Google’s experiment with using Reddit as a data source for training its Gemini AI is a lesson in the absurdity of allowing an AI model to teach itself. Without human oversight, and lacking any kind of “common sense” to filter out clearly ridiculous text, the kind of answers that were generated to fairly mundane questions ranged from amusing to dangerous. In our context, using AI to perhaps assist in generating protocols, informed consent documents, or any kind of literature, by training it on a database of existing examples, would potentially have the same risks. Aside from the fact that the protocols are proprietary information for each sponsor, protocols are notorious for requiring amendments to fix errors or provide clarifications. They are inherently imperfect, as much as we all try to get them perfect! Even if the protocol doesn’t have errors as-written, there are often compromises based on limitations of time, pre-existing data, drug tolerability, subject preferences, or any of a myriad of reasons to choose a particular timeline or set of measurable outcomes. In fact, as research should build upon what has gone before, it makes no sense to simply use old examples in the hope of drafting a novel approach that might be easier, faster, or cheaper to execute.

My experiences in AI training over the last year have been eye-opening, because of the sheer number of people and hours required to properly try to craft and steer an AI towards even a semblance of mediocrity. It was amusing because there the “contamination” of data was at times in both directions – as an excess of incorrectly formatted math problems were offered up an examples, the model started producing solutions written using the same incorrect format, and as the humans were increasingly exposed to AI-generated content, their own human content began to look more and more AI-generated, such that it began to get flagged as such and rejected!

With regards to clinical trials in particular, one area that I found concerning was with medical knowledge and reasoning. It was very obvious that very few actual medical experts were contributing to the process, as it would have been prohibitively expensive to pay for them. With limited knowledge and experience, training examples were overly simplistic and incorrect, and often relied on basic pattern recognition without a logical understanding of why something is what it is. Historically, AI models have been very good at pretending to be smart, while actually falling way down on standard IQ assessments. If the people being used to guide and train the factual knowledge and logical reasoning of AI in these specialized areas aren’t themselves highly knowledgeable and intelligent, then the model truly is doomed. After all, we’ve already established that they do a very poor job of training themselves!

My point here is that, even if we are able to fund and task the experts to help train up AI models on the kind of specialized work required in clinical trials, it’s still going to require (knowledgeable, experienced, intelligent) human oversight to “check their work”. As such, AI might indeed save us a ton of time and typing, but I don’t think it’s going to be the case of asking “Hey Siri, draft me a phase 1 dose escalation study to find the maximum tolerated dose of generimab” and simply emailing it off to the FDA. There is a very real risk of the proponents of AI over-promising and under-delivering. In the specific area of medical monitoring and subject safety, I would not trust an AI to be able to apply the same clinical reasoning skills of a trained physician, no matter how capable they might appear in offering up diagnoses or treatment plans (to be fair, most AI training steers specifically away from this – but my concerns stem from specific attempts to address this niche). Although I have previously argued that safety monitoring is surprisingly specialty-agnostic, compared to protocol design and study start-up activities, one thing we all have in common is having had the same kind of experience-based training. We’re also at the end of the bell curve that has typically been separate from the AI models, where being able to logically reason and apply our knowledge is far more important than simply knowing facts.

Lastly, and this is a huge concern, is the phenomenon of “hallucination”. This is the situation where an AI model, faced with an inability to answer a question due to a lack of factual knowledge or an inability to logically reason its way through a problem, simply makes something up. Even when explicitly instructed NOT to do this, and to instead say something like “I’m sorry, I’m afraid I can’t do that…”, AI seems to be inherently a people-pleaser. This could result in false statements in investigator brochures or consent forms, in inaccurate study timelines as enrollment rates are hallucinated based on non-existent data, or in inaccurate medical coding or protocol deviations. AI-generated hallucinations are by their very nature IMPOSSIBLE to detect from an accurate outcome, unless you know more and better than the AI. And if that is the case, then why are you using the AI to do the work in the first place…?

With all of that said, do I think that we’ll see more AI in clinical research? Yes, I do. Most importantly, AI is quite simply getting better. Recently, and for the first time, an AI model demonstrated an IQ that was above 100 – suggesting some truly useful logical reasoning is being performed. As an industry, AI software companies can learn from the errors and hopefully train up their models on legitimate content with legitimate guidance, and if the tasks are highly specialized and limited then the advantage of an accurate, fast, tireless entity is obvious. Even in areas where human oversight is expected and required, there’s nothing to stop AI from being a useful screening tool and an assistant to tasks such as medical monitoring or safety signal detection.

I am leery of putting too much stock into the promises of AI just yet, but clearly several groups are working on trying to provide meaningful solutions to the clinical research world and things are likely to improve. One thing is for sure though, they won’t improve unless people are willing and able to put the work into refining and optimizing the AI models for these purposes. If you get the opportunity to contribute to this work in any way, I say go for it!

Powassan virus – an “uptick” in cases, or simply better awareness?

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Nick Bennett MD, Public Health, Uncategorized, viruses on May 9, 2024

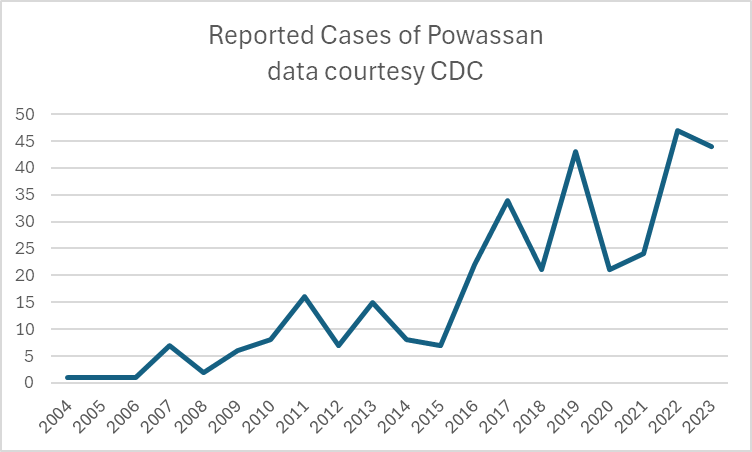

A recent headline caught my eye, discussing an increase in the annual reported cases of Powassan virus – a virus which (for reasons that will become obvious) is near and dear to me. I decided to take a look at the actual data in more detail, and discuss a bit of that here, because understanding viruses like Powassan has implications beyond just this one infection.

Let’s start with what Powassan virus really is – it’s an arbovirus, meaning transmitted by arthropods (in this case, Ixodes ticks), and has an ability to cause a form of encephalitis. It is in fact closely related to the Tick Borne Encephalitis (TBE) virus, but Powassan virus was actually named after the town in Ontario where it was first discovered. It’s highly likely that many (perhaps the majority) of infections don’t go on to cause very serious disease, but the actual risk of encephalitis from it is unknown because the total number of cases isn’t really known. Of the symptomatic cases, about half are quite serious and 10% are fatal. The CDC has made it a nationally reportable infection, but the tricky part is knowing when to even think about it…

I diagnosed the first ever case of Powassan in Connecticut in 2016. It really was a bit of a crazy story, and truly a perfect storm of being in the right place at the right time. A young infant boy was admitted to the ICU with seizures and a very clear story of a few hours of a tick being attached to his leg 2 weeks earlier. The tick was brought into the house on a family member’s clothing, and probably got onto the child during a feed while being held by this person. The medical team had quite correctly ruled out most tick-borne infections due to the very short attachment time, but I knew that there was one exception – at least in animal models, Powassan virus could be transmitted in as few as 15 minutes. So it was possible, but was it probable? The clincher was the MRI report, which had a very distinct pattern showing “restricted diffusion of the basal ganglia and rostral thalami, as well as the left pulvinar”. There was no sign of more widespread of diffuse signal changes as you might see with ADEM (acute disseminated encephalomyelitis) or cerebellar changes as you might see with enterovirus. No hemorrhagic changes, as with herpes simplex. The laterality and location of the damage matched the physical symptoms (motor dysfunction affecting the right more than left), but more importantly it was also similar to previous reported scans from patients with arthropod-borne flaviviruses, including Powassan. Choi and Taylor wrote in a 2012 case report “MRI images of the patient’s central nervous system (CNS) were unique, and when such images are encountered in the clinical setting, Powassan viral infection should be considered.” We were able to test the baby’s spinal fluid at the CDC for Powassan, and it came back positive.

The points to make about this case are several – firstly, the recurring comment from most (probably all) of my colleagues when I made the diagnosis was “What made you think of it?” Honestly, it was mostly the fact that I had training in a state where Powassan was well-known and we would consider it routinely. I simply added it to the differential and saw that not only could I not rule it out, I had some evidence to support it! But the issue here is that there were probably many cases of Powassan over the years that doctors had been seeing, but simply never thought of testing. Powassan was not on a routine viral encephalitis panel in Connecticut (it’s a send-out to the CDC), whereas some other State laboratories like New York test for it automatically on their own encephalitis panel, in addition to sending/reporting to the CDC. It is very much a case of out of sight, out of mind.

Secondly, even if some physicians had considered and tested for the virus somehow, Connecticut didn’t make Powassan a reportable disease until 2019 (more than 2 years after I made the first diagnosis in the state). It’s really hard to measure something if you’re not counting it…and of course even hard to count something if you’re not looking for it!

So this makes it really, really hard to know what to do with news that “Powassan cases are increasing.” Reports are increasing, but so is awareness, and testing availability – it doesn’t mean that actual infections with the virus are going up. It is possible that they are…but the case reports alone aren’t enough to make that conclusion. You really have to understand the reporting infrastructure and testing limitations in the context of a specific disease when trying to interpret the changes you might see in any sort of incidence or prevalence data.

There isn’t a vaccine yet for Powassan virus, although when I last checked research was ongoing (and there is a vaccine for TBE). The best way to prevent infection is to avoid any kind of tick exposure at all – cover skin, use DEET, avoid tramping through the wilderness in areas where the virus is known to be in ticks, and check your pets! Also – change your clothing when you get indoors from activities that might have exposed you to ticks…

Bonus if you’ve made it this far – you can check out my TV appearance on Monsters Inside Me below!

The importance of truly Informed Consent

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Uncategorized on April 21, 2024

I heard a little more recently on the contaminated blood scandal of the 1980s, where huge numbers of people with hemophilia were given treatments for their condition that were contaminated with viruses, including HIV and Hepatitis C.

Early on, there was little knowledge about the true risks of these viruses, and no proper testing available (certainly not widely available), but it turns out that some of this story is even worse than simply being given contaminated blood products.

An inquiry in the UK is currently focused on a specific series of infections that occurred at one particular school, which had a hemophilia treatment center on-site and which, it turned out, was also conducting research into novel treatments for the disease. At a superficial level the research seemed sound – it was asking the question: would a new heat-treated version of the clotting factors needed to treat hemophilia be safer than the standard treatments? Unfortunately, the heat-treatment wasn’t sufficient to completely inactivate the viruses – but the story is much worse than just that.

Several people have come forward who not only were infected with the viruses anyway, but possibly didn’t need treatment for their hemophilia at the time they were given the experimental treatments and, worse, neither they nor their parents were properly consented for the research. When the true risks of infection were obvious, subjects weren’t told, and some weren’t even informed of their infections for a year or more. One doctor involved in the study, a Dr Samual Machin (now deceased) is quoted during the inquiry:

“This would have been discussed with his mother, although I acknowledge that standards of consent in the 1980’s was quite different to what it is now,”

At the time, the subjects were all children, and several of the parents denied being properly told about the research, and that they would not have consented had they been told. Further documents showed that untreated patients were highly sought after, and that trying out the new heat-treated therapy may have been prioritized over the patients actual medical needs.

There are several core principles of research at stake here – beneficence (doing good), non-maleficence (do not do anything bad) and autonomy (being able to make your own decisions). Even a cursory look over the stories of this case show that none of those principles were upheld in this research, and of course the fact that the heat-treatment didn’t work to inactivate the viruses makes it all the worse (arguably if the research was a stunning success there wouldn’t be an inquiry into any of this…but that’s a whole other topic for discussion).

While there are regulatory rules for ensuring proper scientific conduct of research, there are also ethical rules. The two have some overlap, but they really are distinct frameworks, within which researchers have to function. The sad fact is that many of the rules and protections that we now take for granted were imposed as a direct consequence of past unethical human experimentation (which leads to another discussion about how what is considered “ethical” changes over time). From the perspective of human subjects and safety in particular, these are reflected primarily in the document we know as the ICF – the Informed Consent Form.

While it’s true that many aspects of subject safety, rights, and welfare are contained within the research protocol, the protocol itself is a highly technical description of the research and as more of a scientific justification and research plan. The ICF on the other hand is intended to be seen and understood by the study subject themselves, and includes a discussion on the research protocol (visits, procedures, timeline, risks etc.) in addition to making them aware of certain other rights afforded to them, including the right to leave the study at any time and any other treatment options available. The research site’s institutional review board (IRB) would have reviewed and edited the ICF to ensure that it accurately reflected the research risks and benefits prior to being seen by a potential subject. IRBs include subject-matter experts as well as members of the lay public to ensure clarity and understanding. Not only are potential study participants supposed to be given the opportunity to ask questions before signing the ICF, but they receive a copy and a copy remains in their medical record.

The fact that no such process occurred in these contaminated blood product studies is obvious.

Unfortunately, stories like this from research done decades ago, and which clearly doesn’t meet current standards, color everybody’s opinion of medical research. I have had parents refuse to consent for a study because “The sponsor is [insert drug company with research scandal] and I don’t trust them,” even though the drug in the study had nothing to do with the risks from the older scandal. I heard about one parent who turned down a study because of a poorly written ICF, that ironically overstated the risks in a summary paragraph that implied the drug had never been given to anyone before – some people might have continued reading, but this parent did not (they did however provide that feedback to the investigator, so we were able to modify the ICF to make it more clear). One time I had a sponsor try to avoid explaining all the risks (for the control therapy, not the study drug) in the ICF and instead provide a patient hand-out or “your doctor will explain this to you” verbiage. Despite our warning that the IRB would reject this ICF, they insisted on submitting it and of course wasted a whole IRB review cycle as they were forced to revise and resubmit the document with our recommended wording. This wasn’t an intentional thought to mislead, they genuinely thought it was a more efficient process and would avoid scaring the subject unnecessarily, but we knew that the ICF should be a stand-alone record of the subject being truly informed before consenting.

One of my experiences with obtaining consent sticks out to me – it was a slowly-recruiting antibiotic study and I was hoping to not have another screen-failure at my site. I had found a possible subject and was discussing the study with his mother and my study nurse. The mother was asking careful questions, clearly a little nervous (her son was in hospital after all!) and I was thinking that she probably wasn’t going to sign him up when she suddenly said “You know what, you’re the doctor and you know best, I’ll do whatever you say.” Massive red flag to me, as an investigator. Research isn’t the same as medical care – if “I knew what was best” we wouldn’t be having a conversation about a clinical trial! Also, if something were to happen during the study and she had rescinded the decision to me, then she as a mother would feel far worse than if she had made the decision truly believing she had made the best call. So I called “Investigator fiat” and screen-failed them. Every set of inclusion/exclusion criteria includes a line about “any other condition which, in the opinion of the Investigator. would interfere with the conduct of the study” and at that point I’m not sure that she fully understands the risks and benefits.

While we might celebrate some of these stories as holding ourselves to a high standard, the sad truth is the current standards of oversight and training that we have in medical research are much better than they were in the past mostly because of how poor they were in the past. Personally, I find it shocking that some of this occurred within my lifetime, and I think it behooves us to be mindful every day about how we conduct our research, placing the rights and welfare of our participants first.

Regional Medical Monitors – does location really matter?

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Uncategorized on April 5, 2024

In my ongoing saga series on clinical research, I thought I’d share my thoughts on the advantages and disadvantages of requiring regional medical monitors be located in specific countries.

One of the points raised during the planning stages of a clinical trial is often the geographic location of the team members. The Clinical team in particular pretty much has to be based locally because they will be performing site visits and interacting very closely with the staff and investigators, but it’s not unusual for other team members to be based around the globe. Data management team members for example are frequently located in Asia due to a large population of skilled talent available at more economic salaries than if they were based in Western Europe or the USA, and the fact that their work can readily be performed remotely and asynchronously with the rest of the project. But what about the Medical team?

The Medical Monitors are typically physicians with at least some experience in clinical practice (although the actual time people have spent varies considerably), and many have some degree of subspecialty training. The interesting thing is that a very large part of the job is subspeciality agnostic – the safety data we review all looks the same, and it’s largely a case of lining up the findings with the study-specific protocol to weed out the more detailed anomalies. Whether the study drug is being given for one thing or another is largely a moot point. When looking at things like protocol design and study planning and execution, there is absolutely an element of subspeciality knowledge required, but it isn’t that unusual for a physician trained in one area to find themselves working on a clinical trial in another. Furthermore, clinical trials are often global in nature and may have sites not just in different time-zones, but on different continents, and the Medical Monitoring work itself is readily performed remotely. For this and other reasons, the physical location of the Medical Monitor may not be considered relevant, but I would argue that there are very good reasons to keep the Medical team regional and optimized for the study, beyond the simple consideration of time-zones.

In the early planning stages, similar to being a subject matter expert from the disease/treatment perspective, it can be critical to have the insight of a local physician when considering things like screening failure rates, ease of enrollment, site and investigator selection, and even country-specific nuances on treatment guidelines or standards of care. For example, if a protocol requires that a specific comparator drug be used, but that drug isn’t approved or recommended in some countries, then it would be a mistake to try to conduct the study in those countries. Certain medical conditions are more or less common around the world, whether due to genetic or environmental factors, and these can dramatically impact enrollment rates and timelines. While it is true that a lot of this information can be obtained and understood by any physician, I think it’s still prudent to consult someone with that knowledge from a medical perspective.

During one large project I was on, we received feedback that a particular medical test was likely under-budgeted, which might lead to sites refusing the take the study on if it were not reimbursed properly. It was something that was highly unusual in routine medical care, but which I happened to have knowledge of and an awareness of the complexity of the procedure. Having an awareness also of the way the American healthcare system tracked and billed for these tests, I was able to direct the budget analysts to the correct amount to cover which impacted not just the proposal I was currently working on, but any others that used the same test. Someone without that knowledge of how the system worked might not have even known that there was an answer out there to find, never mind find it.

One area that is also important, although it’s often not realized until it’s needed, is clear communication with the sites and Investigators. While it’s true that English is widely used and understood, and tends to be the “lingua franca” of the research world, it’s also true that English is a second language for most. It seems prudent, if not simply polite, to be able to converse with site staff and investigators in their native language, and furthermore to have the social cues and etiquette familiar to them. I can speak French fairly well, but I know I cannot communicate the nuances in French that I can in English. At best, this can slow down communication if a third-party is required on a phone call to interpret in real time – at worst, it can lead to miscommunication and inadvertent offense. I have found that the issues are compounded if a person who natively speaks one language converses in English with someone who natively speaks another, and because clarity and attention to detail are SO important, I think it does behoove us to consider this aspect of study execution when assigning Medical Monitors. I don’t think this necessarily requires physicians geographically local to the sites, but doing so definitely decreases the odds of miscommunication.

Having already said that geographic location is irrelevant when considering the basic data and safety review tasks (with the exception of nuances in country/region specific regulatory reporting of urgent cases), there is other reasons for appointing Medical Monitors in alternative locations to the main study sites, especially if the time-zones at least line up. For one, it may be economically advantageous to hire on physicians from certain countries, or the volume of work may simply require multiple people with the team members scattered. There is also the very real possibility that the most experienced or suitable physician for that study isn’t local, or the sponsor may have a specific preference based on past experience with that person, so obviously a number of factors need to be considered.

Importantly, because the needs are different for project development versus execution, It may be the case that the subject-matter expert assigned to the initial proposal team isn’t assigned as the Medical Monitor. In that situation, it’s crucial for a comprehensive hand-off/kick-off meeting to occur to make sure that any issues or risks identified during the initial work are communicated over to the main team.

From the perspective of the sponsor, I would consider all of these issues when looking at the Medical Monitor assigned to your study – what aspects are most important to you, and what tasks are they most likely to be performing? I would say that if site communication and insights are important, then advocating for a local assignment would be a good idea. If you consider that subject-matter or clinical trial design expertise is more important, then you may want to be targeted in your selection regardless of geographic location. I am also a huge advocate for remote working for Medical Monitors, especially when considering all the factors above: there is a finite pool of experienced experts and if you happen to find someone with the right mix of clinical and research time, covering the right subject-matter, and with the personality and work-ethic to excel in clinical research, you absolutely should not limit your recruitment to physicians who are willing to relocate. Most physicians who are at the stage in their careers where a move to industry is feasible are in their middle years, settled with children and houses, and in many cases burned out with the time and demands of clinical care. Being told they have to uproot their family and commute through traffic to a desk job in an office is not appealing at all. I have seen several companies, both in the CRO world and in big Pharma (less so in Biotech interestingly enough), require their Medical Monitors to relocate and work on-site. I simply do not think there is a need for that in this line of work, especially in the post-pandemic era where work-from-home infrastructure is so well developed. If you’re requiring your talent to relocate you’re effectively giving the talent away to your competitors…

What’s been your experiences working as, or with, a regional medical monitor? I’d love to hear about the advantages and challenges you’ve experienced.

Should I get the COVID vaccine?

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Uncategorized on November 22, 2020

TL:DR – Yes.

*Tap tap* – is this thing still on? It’s been a while.

The recent slew of data coming out from Pfizer and Moderna about their respective COVID vaccines has prompted a LOT of discussion about their utility, safety, and efficacy. I’ve had friends and family hit me up for my opinion through social media, private messages, and phone calls, and the truth of the matter is there’s a 50% chance I’ve already got a vaccine, and if I haven’t the company is looking to provide it to those in the placebo arm. Yes, I’m in a COVID vaccine clinical trial – the science and need is compelling.

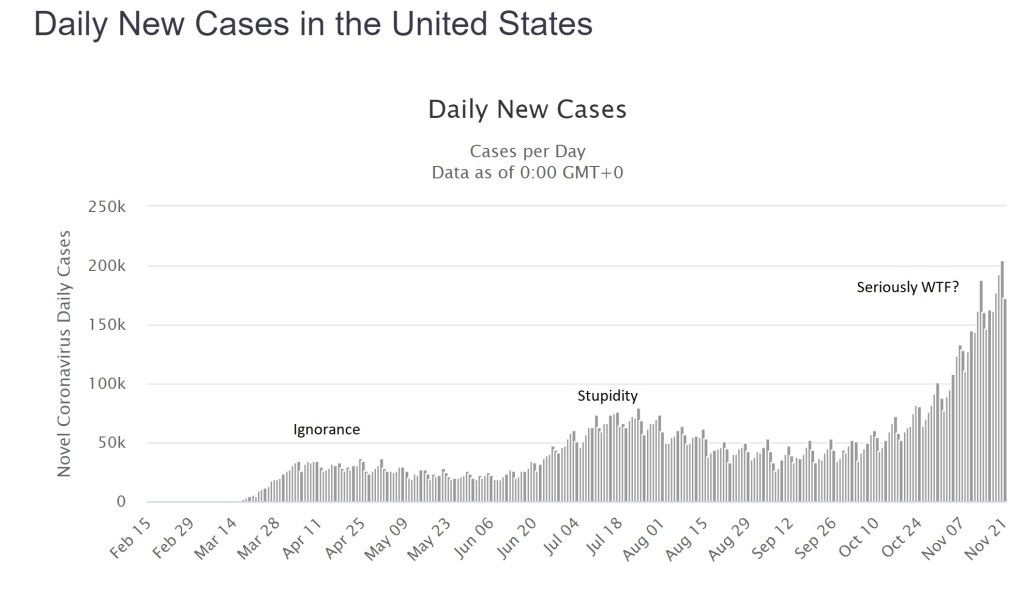

The global cases of COVID continue to climb with over 58 million worldwide as of today, of which about 12.5 million are in the US. Facing an accelerating “third wave” of cases of around 200,000 new reports and 2,000 deaths from COVID every day, there is no end in sight. This isn’t a hoax, it isn’t a “plandemic” or some other bizarre conspiracy theory, and it didn’t go away after the election – what we are dealing with is a predictable novel infection, likely zoonotic, the effects of which have been made worse by a series of abject failures in public health and education. I’m not going to debate that – it’s a matter of fact. Trolls will have their comments happily deleted, because I don’t argue with people who are wrong.

Having failed miserably to prevent the spread of this infection through such simple measures as staying home and covering faces, we now appear to have little option but to have faith in a vaccine of some kind. Herd immunity will otherwise cost millions of lives and probably trillions of dollars in lost productivity and economic output. The “low” mortality of 2-3% for COVID-19 is not low at all (the risk of death from a car crash is half of one percent, yet no-one in their right mind would recommend deliberately crashing their car…), and in any case the long-term effects of the infection on peoples’ health is likely to impact society for years to come. The fastest, safest way to stop the virus is through vaccination.

There are two vaccine candidates that have made headlines recently, both with similar technologies and claims of effectiveness, so for the sake of simplicity I’m going to talk about them generically. It seems likely that one or both of them will be approved by the FDA.

The vaccines use a “new” technology called “messenger RNA” or “mRNA”. The concept of an mRNA vaccine is not in fact new, and they have been researched for years. mRNA is entirely natural – every cell in your body contains some – very simply it is used as a go-between (a messenger…) from the genes coded within your DNA to the ribosomes where proteins are made. mRNA has a very specific structure – a linear molecule consisting of a mixture of 4 different nucleotides (adenine, cytosine, guanine and uracil) with a cap and a tail to ensure that the code is translated correctly and that other bits of RNA aren’t used accidentally. After the mRNA molecule is translated it is simply degraded and the individual nucleotides are recycled.

In theory, and apparently in practice, the use of an mRNA molecule as a vaccine would have several advantages. Most vaccines can be divided into one of two types: killed (or subunit) and live-attenuated. mRNA vaccines manage to combine the positive aspects of BOTH kinds, but the negative aspects of NEITHER. Allow me to explain.

In a normal viral infection the virus has to invade the body and evade the immune response, then infect a host cell. Viruses cannot replicate without a host cell, but in many instances the virus infection damages the cell function such that the host is affected and becomes sick. A virus that successfully infects a cell can take over the cellular functions, produce viral mRNA molecules, and force the cell to produce viral proteins. Cells though have several lines of defense, from producing chemicals called “interferons” that combat viral infection, to presenting viral antigens on their surface to the immune system (specifically, CD8+ T lymphocytes). Whether through the “innate” immune response like interferons, or through the “adaptive” immune response like T cells, nearly all of the time the host is able to successfully contain and clear a viral infection.

With a live-attenuated vaccine the goal is to mimic the natural infection, but without putting the host at risk of getting sick. The vaccine is usually made in such a way that the virus is defective and some aspect of its life-cycle is damaged – this means that the virus will still infect a cell and will still present its proteins to the host T cells, but the host simply won’t get as sick as they would with a wild-type infection. The result is often a VERY effective immune response that can last a lifetime after a single dose of vaccine, although sometimes boosters are given a few years later. Examples are measles, mumps, rubella, yellow fever, and oral polio vaccine.

Killed vaccines on the other hand use only “bits” of the virus, usually proteins that make up the capsid or outer membranes that are targets of the host immune response in natural infection. The hope is that by showing the host the purified proteins the immune system will produce a response that will recognize the virus should it try to infect the host in the future. The downside of these vaccines is that the type of immune response is slightly different, as the proteins are not presented from *inside* the cell. As such, the T cell responses are typically less, but instead there is a strong antibody response. Antibodies are very good at recognizing and neutralizing infections outside of cells, but of course since viruses replicate inside cells the real immunity actually depends on those CD8+ T cells. As such, killed vaccines often need multiple doses to be effective, and may not provide as much protection as the live vaccines would. Their advantage though is safety – there is literally no way for a killed vaccine to give the host an infection, whereas live-attenuated vaccines CAN cause disease if the host has an immune deficiency or if the virus mutates.

Looking now at mRNA vaccines it would seem as if they have the benefits of live-attenuated (internal protein production and presentation to T cells) AND the benefits of killed vaccines (no risk of causing infection in the host). In addition, despite the conspiracy theories you may read about online, there is no risk that the vaccine “becomes part of you” since there isn’t a mechanism for it to do so. Furthermore, a COVID-19 mRNA vaccine is an even better deal. The virus that causes COVID-19 has two very problematic aspects to it – firstly, it directly and significantly decreases that innate interferon response that is intended to stop the virus becoming established. This is likely because it evolved in bats, which have inherently high levels of interferon. In a human host, this virus is able to suppress our immune system very effectively, so that an otherwise mild infection is far more serious. Secondly, the adaptive immune responses (especially the T cell responses) in patients with COVID are also suppressed. Very early on it was obvious that the sickest patients with COVID had low number of lymphocytes, and over time we have come to realize that this also led to decreased adaptive immune responses against the virus. It seems that without the normal early response to infection, the host immune system is led awry, causing a dramatic, abnormal immune response that misses the target entirely and leads to the characteristic lung inflammation that has become a hallmark of the infection. What this means in practical terms, is that people who suffer wild-type infection often don’t mount great immune responses to the virus (reviewed here), and those responses seem to drop away with time. In other words, there may not ever be a population of truly immune people from this infection.

The only way to get immunity may be through an effective vaccine.

Both of the mRNA vaccine candidates, and other vaccines in development, have already worked to address this concern by demonstrating not only the typical antibody responses measured in most vaccine trials, but also effective T cell responses. This means that, on paper at least, we already have some reassurance that the immune response to this vaccine approach is meaningful and robust. In recent days, we have also learned that there is evidence of real-world protection for those who received the vaccine.

Both vaccine manufacturers have claimed around 95% “vaccine efficacy” from their vaccines. Now, this term has led to a lot of confusion, even among physicians, about what it really means. It does NOT mean that 95% of the subjects were protected. It also doesn’t mean that 95% of the subjects didn’t get the infection. It means that the risk of getting the infection was REDUCED by 95% compared to those who didn’t get the vaccine.

In real terms, the Pfizer numbers are a good example. Among the unvaccinated group, during the timeframe of followup (a minimum of 2 months) 162 patients were diagnosed with COVID. Among the group of vaccinated individuals over the same timeframe, there were only 8 infections.

The groups were randomized 1 to 1, meaning that approximately equal numbers of subjects should be in each group, and because the vaccine was randomly assigned the mix of ages, male/female, exposure risks etc ought to also be approximately equal between the two groups. So…one would also have expected around 162 infections in the vaccinated group, if the vaccine was not effective. Having only 8 infections is a huge decrease, which is where the “95% vaccine effectiveness” comes from.

What are the real world implications? There were over 43,000 patients enrolled, so approximately 21,500 would be in each group. 162/21500 is a rough guess of 0.75% of the population getting infected (although of course those people were enrolled over several months of time so the math is only a crude calculation). Those numbers mean that even without a vaccine, 99.25% of the placebo group didn’t catch COVID! I have heard arguments that the type of people who would enroll in a clinical trial like this may be more likely to wear masks and practice social distancing, which may be true, but if anything this would make it harder to detect a difference between the two groups, not easier – and the calculation of vaccine effectiveness doesn’t rely on knowing that. Nationally over the summer the average number of new cases in the US was about 50,000 a day. Over two months (approximately the average length of followup for the study participants, and the minimum required for safety data) that works out to 300,000, or about 0.9% of the total US population. This number is reassuring for two reasons – firstly it fits with the theory that the study participants were perhaps at a slightly lower risk of catching COVID compared to the national average, BUT the difference isn’t so great that it immediately calls the results into question. If the national rate was more like 10% and the study placebo rate was the 0.75% observed, it would look very suspicious. In theory, if the US population had been immunized over the summer instead of 50,000 cases a day, we would have had only 2,500 cases a day.

In addition, the safety data look great – significant fatigue and headache in 2-3% of the Pfizer participants after the second dose (I couldn’t find good data on the larger Moderna study, but the dose used in the Phase III study appeared to be well tolerated in earlier Phase II work). Now, admittedly we don’t have long term followup for several years because these vaccines are new, but intuitively and biologically we shouldn’t really expect any nasty surprises based on how the vaccine works in the body. One concern raised by some scientists and physicians is the possibility that the vaccine will induce an immune response that will make future infections worse – honestly, if that were the case we would have seen it in these clinical trial results. Among the “severe” COVID infections, in the Moderna study 0 of 11 cases were in the vaccinated group, and in the Pfizer study only 1 of 10.

So what do we have overall? We have a vaccine technology that induces biologically relevant immune responses that should be better than those of the real infection, with minimal risk. We have two clinical trials demonstrating dramatic differences between the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups that support highly protective vaccines. We have at best blunting of the epidemic from social distancing and masking, and an abject failure at containing it. Honestly, getting a COVID vaccine ought to be a no-brainer – it’s literally our last, best hope of getting back to something like normal, and it’s going to save millions of lives.

At the time of writing Dr Bennett has no financial conflicts of interest in any COVID vaccine product or company. He is a participant in a COVID vaccine study. Several of his friends have caught COVID (one was hospitalized), along with two non-immediate family members. Wear a damn mask.

Healthcare as a Right?

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Uncategorized on January 31, 2012

Firstly I want to preamble this with the fact that I’m obviously biased. I was trained in a national health service and I’ve spent my entire medical career in an academic medical center, somewhat sheltered from the pressures of medicine as a business and surrounded by Docs who certainly didn’t go into medicine for the money. No-one in Pediatrics does it for the money… So my impression of how a Doc should think about medicine and patients may not jive with everyone else’s. That’s fine. But I did want to put down my thoughts on healthcare as a part of society – how we should think of it, and therefore how we should pay for it. My opinions at least have a lot of facts to back them up, in fact I have these opinions BECAUSE of these facts – there is simply no other way I can interpret them.

One of the most contentious parts of the United States Affordable Care Act (healthcare reform, the misnomer “Obamacare” or whatever you want to call it) is the “Mandate” – the requirement that everyone needs to purchase some form of healthcare insurance, or pay an additional amount on their income tax return. What this does is bring the US in line with every other developed nation in having universal healthcare (coverage for all its citizens). The existing systems of Medicare (for the Elderly) and Medicaid (for the Destitute – the only way I could keep them straight as an outsider) have huge coverage gaps, and healthcare costs are the leading cause of bankruptcy in the US. This is embarrassing. Or at least, it should be.

Instead, there is a prevailing view among many that “The US has the best Goddarn Healthcare System in the World!” and any attempt to change it will drag it down.

Hardly.

The US is 38th in the world ranking for life expectancy. Cuba is 37th. EVERY other major industrialized nation ranks higher. And they all have universal healthcare. Childhood mortality in the US is also at the bottom of the pile. The WHO rates the US as 1st in terms of in cost, 1st in responsiveness, 37th in overall performance, and 72nd by overall level of health.

Despite these mediocre results, the US pays more than anyone else. In fact the healthcare spending in the US is almost TWICE that of anywhere else, with the exception of the island nation of Bermuda where it’s about the same.

So something dramatic has to be done, of that all sides agree. But why are there even sides? What are the arguments for and against universal healthcare, or in other words to consider healthcare as a right?

The Golden Rule

“Treat people as you would like to be treated.” Since I love the fact that I don’t have to worry about catastrophic medical costs, and my employer pays for most of my medical insurance, I think it would be awesome if everyone had that. It has made headline news for years, how many millions of Americans are uninsured and as a result decline healthcare (or leave it too late) since they can’t afford it. The issue is compounded since those who are in good jobs (and could afford to live without insurance) already have health insurance, typically heavily subsidized by their employer – so they may only see 10-25% of the actual premiums. For those without this luxury, or those who were in a job but lost it and had to pay COBRA to extend coverage, the true price of healthcare premiums is shocking. This simply exacerbates the healthcare divide. Medicaid will pick up the pieces for the very bottom of the pile, but there is a big chunk in the middle who don’t fit. It is only humane that everyone gets the same opportunity, regardless of income or employment status.

If you disagree with that, then you’re basically saying that some people don’t deserve to have access to good healthcare. That’s mean, and probably morally indefensible. Who actually WANTS another human being to be sick?

The insurance companies

Oops, was that bad word placement? No, not really, but sometimes it does seem that way. I have lost count of the number of times I have had to fight with insurance companies to get approval for a test (!) or treatment for a life-altering or life-threatening diagnosis. Insurance companies are not there to pay for your healthcare – their agenda is profit, and they will do anything they can to deny payment since it hurts their bottom line. If their agenda was patient care, they wouldn’t fight these fights. The documentation that goes into justifying reimbursements is crazy. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was targeted primarily AT the insurance companies, since Congress effectively gutted the ability of the bill to do anything else more meaningful. What it basically said was “You can’t ‘Not cover’ someone because they’re sick, you can’t stop paying because people get sick, preventative healthcare should be 100% covered, and you have to allow kids on their parent’s plans until 26”. This targeted the most vulnerable people – those with serious or pre-existing illnesses who would be excluded from plans (to help the bottom line) and young adults who weren’t in jobs with healthcare benefits. However, there was an issue here. If you add all these people onto the list, you WILL increase payouts. That is inevitable. Little Sally’s chemo for her leukemia doesn’t some cheap… You need a large number of non-claimants in the system to keep things reasonable, and this is where the Mandate comes in (my initials, for emphasis). If everyone is on board, revenues can keep up better with the payouts. Simple math. Since it is only humane and humanistic to want everyone to be healthy, everyone has to be in the game. Everyone needs to be covered.

The Mandate

The Mandate is nothing new – Govt has imposed mandates on all sorts of things – they’re called “Laws” – for hundreds of years. There have been efforts to Mandate healthcare coverage going back to the Founding fathers, from the Left and the Right. This should be an issue that has no party lines – and yet here it does. Why? The biggest criticism is individual choice. There is no choice about it – well, there is, but you then have to pay more on your tax return. Hey, that seems unfair…what if they can’t afford it…? Well the ACA establishes insurance markets to help individuals purchase plans more fairly, it sets up a special plan for patients with pre-existing conditions, AND if you’re low-income the plans are subsidized AND the penalty is reduced, or even waived. Bottom line – no-one should be on the hook, at least no more than they are now! However, this is a hodge-podge approach. People can still opt-out, and pay the fine (which incidentally, is used to reimburse the healthcare system when they DO use it as an uninsured patient…) and religous-political restrictions have been placed on certain plans in the exchanges carrying abortion coverage. (Wait, wasn’t there a separation of Church and State in the US…never mind).

But the funny thing to me is that either (A) You already have coverage and aren’t affected by the mandate, or (B) you don’t have coverage and WILL GET HELP GETTING IT. It’s a win-win. Who DOESN’T want healthcare coverage? Do you really want to exercise that right, put yourself (and your family) at risk of massive financial losses AND put the rest of society on the hook for your bills when you can’t pay up? Hardly fair. There is an element of social responsibility here. The Mandate isn’t the Government forcing you to do something that is solely about individual choice, it’s helping you do something that is frankly irresponsible of you NOT to do. Personal choice is only ok so long as it doesn’t impact others, whether you intend it to or not. At some point, personal choice is NOT ok – and as a society we decide where that line is drawn (see next section).

Some (myself included) have argued than a mandate to purchase some kind of insurance is nothing new – think of car insurance after all. Others have countered that not everyone has a car, and they don’t have to purchase insurance. Yeah, but since everyone needs healthcare, doesn’t that help the “Healthcare should be a right” argument? Since we all need it, we should all get it, and we all have a responsibility to maintain it.

Social Justice

We all live in a society – be it a tent village in the Amazon or a metropolis like Los Angeles. In that society there are certain rights, and responsibilities. We expect people to treat each other a certain way. As a whole we don’t steal from, rape or kill each other and can go about our lives in a reasonably predictable and productive manner. We expect people to stop at red lights, and we in turn are expected to stop. So how does this fit into healthcare? Well, since it’s morally indefensible to argue that some people are more deserving of healthcare than others, and that in order to provide protection for everyone we have to have everyone on board, THIS is where social justice comes in. If you want to benefit from the system, you have to be part of the system. Since you CANNOT avoid being part of the system (short of moving out of the country), you have to contribute. The only difference between a mandated health insurance bill and a mandated tax is the lettering on the bill. It is money going from you to somewhere else for a service (protection from healthcare costs).

The US needs to think of healthcare differently, since we know that everyone needs it, as part of our social fabric as much as clean water and clean air are. If they are part of the social fabric, we should expect government help to get it, and that means we should be expected to contribute to support it. The US has, mostly, moved out from the days of the Wild West – healthcare seems to be the last frontier to go.

Let’s look at another aspect of American society – we all expect to be able to dial 911 when we’re being burgled, or our house is burning down, and the police and fire department will show up, free of charge to help. The ambulance will show up too if you dial 911…but they’ll send you a bill afterwards. Why doesn’t that strike anyone as odd?

Single payer – the Public Option

This, in most reasonable people’s minds, is really what “Obamacare” was all about. A government health insurer for all. It doesn’t exist. It was stripped from the ACA in order to get the insurance reforms through, so although the ACA went through it lost the most important part of it. Why do I consider this important? What are the advantages of single payer? Well, for starters instead of dealing with the HUNDREDS of insurance companies there would be one. The plethora of billing staff who exist solely to shuffle paper around and sort through this mess wouldn’t exist. Fully 30% of private healthcare dollars is wasted on administration (ie doesn’t reimburse for the actual medical care) whereas for Medicare, one of the US Govt plans, it is closer to 3%. That’s quite a difference. In addition, the public option would streamline the whole “Mandate” thing, avoiding the situation where we are now with a Govt mandate to purchase a private company’s product.

This wouldn’t be Govt-run healthcare, it would be Govt-financed healthcare. Same Docs, same hospitals and labs, much easier reimbursement system. Insurance companies were terrified that a Government-sponsored plan would put them out of business, with its improved efficiency, larger insurer based and no need to kow-tow to CEO’s and shareholders for profits. This is why they lobbied so hard to strip it out of the ACA. That alone should tell you something about the Status Quo and how messed up it is.

Reimbursements

This is where many of the physician complaints are coming from. It is well known that Govt reimbursements are lower than insurance companies’ reimbursements. There is a concern that a single-payer plan from the Govt would hurt Doc’s salaries. It might. But if you can fire all your billing staff that is a smaller overhead to pay for 😀 There are also the issues of Doc’s incomes going to unimportant things like, y’know, massive student loans and malpractice premiums. The fact is, there may not be a great solution here. Short of asking medical schools to stop charging so much, and asking patients not to sue so much, those things are going to remain. Doc’s salaries are high in the US, but aren’t even the biggest part of the problem – drug costs and institutions take a huge chunk too. The pharmaceutical companies and hospitals have their part to play in fleecing the consumer and driving up healthcare costs, which ends up hurting everyone in the long run. One solution is to scrap it all and start again. Another is to tackle one piece at a time, like insurance companies abuses, and work towards a better system. This is what the ACA is all about – one step in the right direction.

My personal opinion is that salaried Docs would help a bit – remove the incentives to prescribe and test inappropriately (you know docs can actually bill more for doing that, even if it’s unnecessary…?). Lower salaries would mean the Docs who were in medicine were less likely to be doing it for profit (instead of for the patients). If we can change the entire mindset of medicine towards it being a public service, and Docs as public servants (rather than a for-profit enterprise) it might help. But this would need massive overhaul from the ground up…and what to do with all those newly graduated docs with loans to pay etc? So much to fix….

Rationing

The “R” word, the big scary “Death Panel” myth, the fear of some nameless bureaucrat controlling your healthcare. Well, it’s already here. Insurers dictate what does and does not get covered, which in turn dictates what your Doc will or will not provide to you. Medical judgment is often not a part of the decision it seems to me – at least, every time I have spoken to a real medical director of an insurer to fight my case they have agreed with me. Every time – which implies they either weren’t involved with the case or didn’t understand it until then. With a finite pot of resources though SOME form of rationing is inevitable. The difference to me is intent – do you want a public service rationing resources so the most needy can access them when they need to, or a private company rationing them to help their bottom line? Do you want a system where the billing requirements of various plans dictate who gets what care, or the same system for everyone?

There will always be a role for private medical care, but basic, life-saving and emergency healthcare should be free. We’re not talking facelifts and tummy tucks on the public purse here…!

The Constitution

Finally I have something to say on whether or not the ACA is Constitutional. Some people have dragged up various aspects of the Constitution (or rather, its Amendments since it needed fixing along the way…) against the Mandate. In the Declaration of Independence (the document through which Abe Lincoln said the Constitution should be interpreted) the following is said:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

It is hard to pursue happiness, be truly free, and ultimately live, without good health. It’s hard to be healthy without healthcare.

That is all.

Links to facts quoted above:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Health_care_in_the_United_States (wiki)

How the Performance of the U.S. Health Care System Compares Internationally, 2010 Update

Insuring America’s Health – Principles and Recommendations (Institute of Medicine)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_health_care_expenditures

An explanation

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Uncategorized on August 6, 2011

After a long hiatus, I guess I’m back to blogging. Why? You may ask. Or you may not, but I’m going to tell you anyway.

After spending a good portion of the past year or more on Twitter, I have found that (a) some people actually are interested in what I have to say and (b) Twitter has it’s limitations in how I get to say it. Sometimes nothing beats a good old fashioned diary entry.

That’s why I’m here. But why not just resurrect the old site, aidsmyth.blogspot.com? I guess because it had a limited remit, and I’ve wandered off from that track a bit. I’ll still throw up anti-AIDS-denialist stuff, but the anti-vaccine movement is rather closer to home for me right now as well as my other professional interests in antibiotic overuse.

The other thing I spend my time doing is practicing and teaching patient-centred care – the idea that medicine should take into account patient fears, ideas and expectations. Now I can pass comment more fully on what are often complex issues, that a simple re-tweet or Twitter-rant can’t fully do justice to.

Hence the title of the blog, a double-meaning combining aspects of both infectious disease and patient-centered care. Culture. Sensitivity. Geddit?