Archive for category viruses

Powassan virus – an “uptick” in cases, or simply better awareness?

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Nick Bennett MD, Public Health, Uncategorized, viruses on May 9, 2024

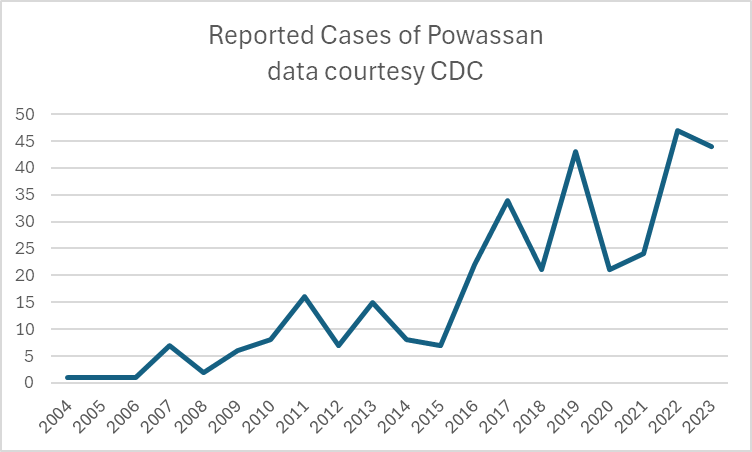

A recent headline caught my eye, discussing an increase in the annual reported cases of Powassan virus – a virus which (for reasons that will become obvious) is near and dear to me. I decided to take a look at the actual data in more detail, and discuss a bit of that here, because understanding viruses like Powassan has implications beyond just this one infection.

Let’s start with what Powassan virus really is – it’s an arbovirus, meaning transmitted by arthropods (in this case, Ixodes ticks), and has an ability to cause a form of encephalitis. It is in fact closely related to the Tick Borne Encephalitis (TBE) virus, but Powassan virus was actually named after the town in Ontario where it was first discovered. It’s highly likely that many (perhaps the majority) of infections don’t go on to cause very serious disease, but the actual risk of encephalitis from it is unknown because the total number of cases isn’t really known. Of the symptomatic cases, about half are quite serious and 10% are fatal. The CDC has made it a nationally reportable infection, but the tricky part is knowing when to even think about it…

I diagnosed the first ever case of Powassan in Connecticut in 2016. It really was a bit of a crazy story, and truly a perfect storm of being in the right place at the right time. A young infant boy was admitted to the ICU with seizures and a very clear story of a few hours of a tick being attached to his leg 2 weeks earlier. The tick was brought into the house on a family member’s clothing, and probably got onto the child during a feed while being held by this person. The medical team had quite correctly ruled out most tick-borne infections due to the very short attachment time, but I knew that there was one exception – at least in animal models, Powassan virus could be transmitted in as few as 15 minutes. So it was possible, but was it probable? The clincher was the MRI report, which had a very distinct pattern showing “restricted diffusion of the basal ganglia and rostral thalami, as well as the left pulvinar”. There was no sign of more widespread of diffuse signal changes as you might see with ADEM (acute disseminated encephalomyelitis) or cerebellar changes as you might see with enterovirus. No hemorrhagic changes, as with herpes simplex. The laterality and location of the damage matched the physical symptoms (motor dysfunction affecting the right more than left), but more importantly it was also similar to previous reported scans from patients with arthropod-borne flaviviruses, including Powassan. Choi and Taylor wrote in a 2012 case report “MRI images of the patient’s central nervous system (CNS) were unique, and when such images are encountered in the clinical setting, Powassan viral infection should be considered.” We were able to test the baby’s spinal fluid at the CDC for Powassan, and it came back positive.

The points to make about this case are several – firstly, the recurring comment from most (probably all) of my colleagues when I made the diagnosis was “What made you think of it?” Honestly, it was mostly the fact that I had training in a state where Powassan was well-known and we would consider it routinely. I simply added it to the differential and saw that not only could I not rule it out, I had some evidence to support it! But the issue here is that there were probably many cases of Powassan over the years that doctors had been seeing, but simply never thought of testing. Powassan was not on a routine viral encephalitis panel in Connecticut (it’s a send-out to the CDC), whereas some other State laboratories like New York test for it automatically on their own encephalitis panel, in addition to sending/reporting to the CDC. It is very much a case of out of sight, out of mind.

Secondly, even if some physicians had considered and tested for the virus somehow, Connecticut didn’t make Powassan a reportable disease until 2019 (more than 2 years after I made the first diagnosis in the state). It’s really hard to measure something if you’re not counting it…and of course even hard to count something if you’re not looking for it!

So this makes it really, really hard to know what to do with news that “Powassan cases are increasing.” Reports are increasing, but so is awareness, and testing availability – it doesn’t mean that actual infections with the virus are going up. It is possible that they are…but the case reports alone aren’t enough to make that conclusion. You really have to understand the reporting infrastructure and testing limitations in the context of a specific disease when trying to interpret the changes you might see in any sort of incidence or prevalence data.

There isn’t a vaccine yet for Powassan virus, although when I last checked research was ongoing (and there is a vaccine for TBE). The best way to prevent infection is to avoid any kind of tick exposure at all – cover skin, use DEET, avoid tramping through the wilderness in areas where the virus is known to be in ticks, and check your pets! Also – change your clothing when you get indoors from activities that might have exposed you to ticks…

Bonus if you’ve made it this far – you can check out my TV appearance on Monsters Inside Me below!

Stressed about Strains

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Research, viruses on December 20, 2020

Many of my friends live in the UK, and have now been put under a “Tier 4” lockdown in response to rising case numbers, particularly in London and the South-East of England. Along with this news is the reporting of a “new strain” of the SARS-CoV2 virus thought to be responsible for this surge. The Interwebs are now aflame with doom and gloom scenarios of vaccine futility, global spread, and the basic fear that new = bad. Now, this is still 2020 so of course people can be forgiven for feeling that way, but if anything the facts are reassuring.

The simple truth is, the UK would have to enact harder lockdown efforts based purely on the rise in cases recently, regardless of whether or not a new strain was identified genetically. It is a total misrepresentation to suggest that the UK is locking down BECAUSE of a new strain – they are locking down because of a rise in cases. New strains have been reported throughout the pandemic, most notably the 614G mutation that arose in the spring but is now the predominant strain worldwide. In many ways the panic surrounding THIS particular strain is due to awareness rather than any hard data.

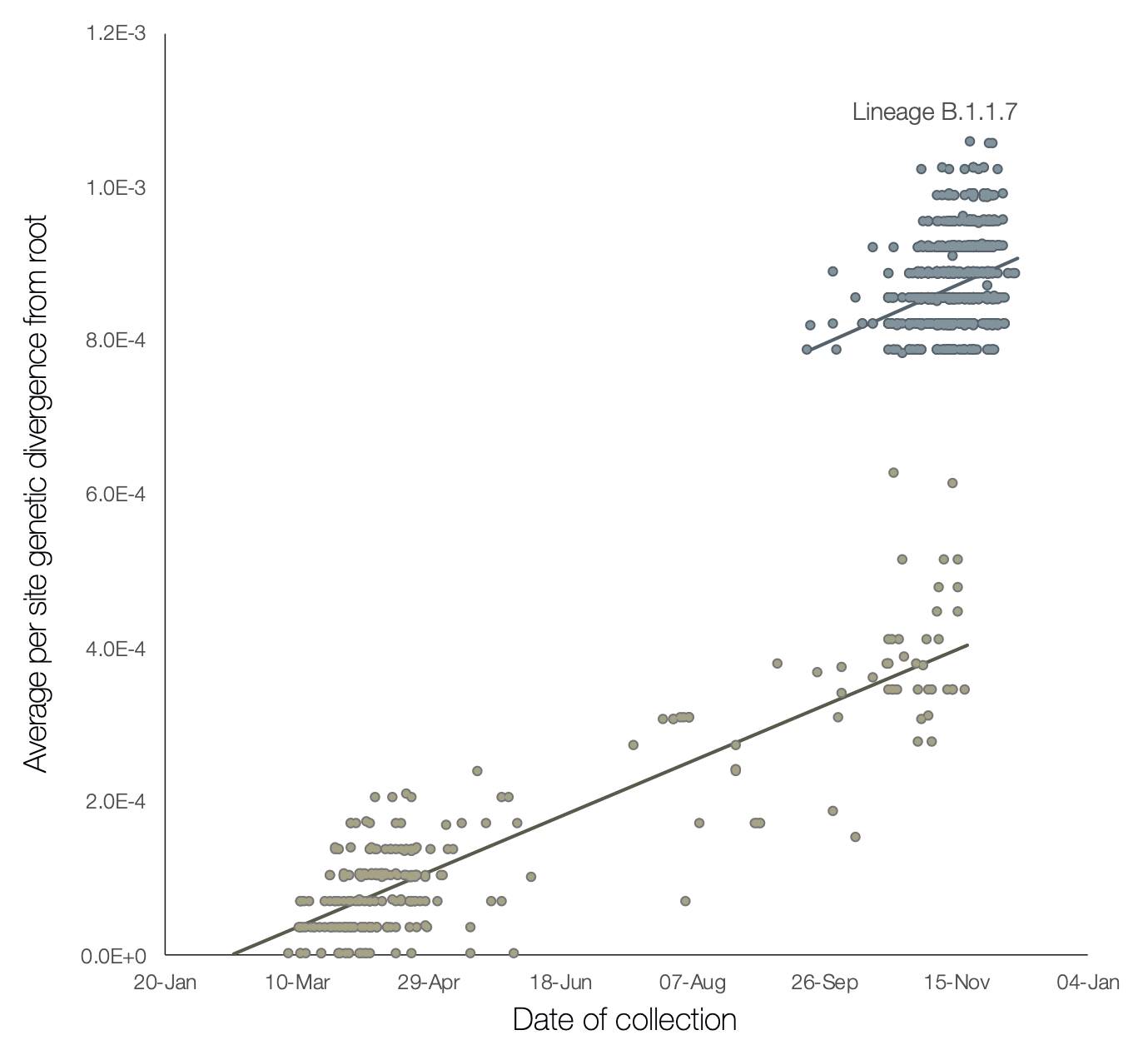

There is no doubt that the UK has failed at containing COVID-19, but not only is there a second wave of infections starting from September, there is a sharp 3rd spike over the last few weeks. This is truly an unusual graph, and not one that I’ve seen quite so dramatically elsewhere. A report in the British Medical Journal, and further outlined elsewhere tells more of the story, and perhaps explains that new surge in cases. A graph from that last paper by Rambaut et al shows the frequency of detection over time, and the genetic divergence, of SARS-CoV2 isolates in the UK.

Firstly, if you look at the lower cluster, it shows a slow increase in genetic diversity over time, as expected with this virus anyway (1-2 mutations per month). You can’t really compare disease incidence with this graph because only a subset of isolates are going to get sequenced, but you still get the sense that there was a peak in the spring and less over the summer. The cluster in the top-right is entirely distinct – firstly the diversity is way off from the trendline of the previous infections (which are still ongoing) but also the proportion of current isolates coming from this new cluster seems to be high.

The obvious worry is that the new strain is more infectious – but the evidence for that is still circumstantial. Just because more cases are occurring doesn’t mean the new strain is responsible – after all, it also true that more widespread infection will make the appearance of significant mutations more likely. There are several mutations identified in this strain within the spike protein that could, in theory, render it more infectious by altering it’s receptor-binding properties (after all, that’s thought to be why SARS-CoV2 is more infectious that the original SARS). The affected sites DO appear to alter receptor-binding and entry locations, and so there is a little more of a “smoking gun” regarding infectivity than merely seeing high numbers of cases – see the section “Potential biological significance of mutations” in the Rambaut paper.

Importantly, there is apparently not sufficient change in the S protein to affect the likely vaccination targets…although honestly we will have to see how the real world data looks with that. The Pfizer vaccine is a whole-protein target with many more places for the immune response to target than just the receptor-binding area at the top. Worries that this “new strain” will render the entire vaccination effort meaningless are not founded in any fact at this point, since all this virus really is, is a slightly different strain of the same virus, to which it remains about 99% the same (8 mutations in a protein that is over 1200 amino acids long…)

And lastly, there is the intriguing finding that some of this new lineage of virus contains a series of mutations in a gene called “ORF8” (simply, open-reading frame 8). This gene is thought to be involved in hiding from the host immune response, by downregulating the protective antiviral system called MHC-1. Similar mutations have been reported before, and not surprisingly the virus is less dangerous. In a small series from Singapore, 28% of patients with wild-type COVID required oxygen, compared to 0% of those with the ORF8 deletion. Rambaut et al hypothesize that this UK strain arose from prolonged infection in an immune-compromised host, perhaps having been treated with multiple antiviral therapies. This would explain the cluster of mutations all appearing together, as well as the potential loss of ORF8 (since it would pose no advantage to the virus to keep it).

And let’s have a quick look at the daily deaths from the UK. While the daily cases are 5-times higher than back in the spring (25,000/day versus 5000/day), the daily deaths are half as high (500/day versus 1000/day). While this reflects a mix of improved management of cases, perhaps different age demographics, it also begs the question as to whether the virus itself is simply less dangerous than it was before.

Looking at this information, I see it that while this may indeed be a new strain, it is not a reason to panic. We have no real reason to suspect that it’s going to affect the vaccine efforts, and absolutely no reason to suspect that it’s any more dangerous than before. In fact, there is a suggestion that it may be LESS dangerous than earlier circulating strains. We should be thankful that scientists are tracking and reporting this data, and remember that any new mutations that do render the current vaccine ineffective can be engineered into a new mRNA vaccine extremely quickly. The important thing is that in order to contain this virus we do exactly what we’ve been doing already – isolating, masking, and continuing our vaccine program.

Something old, something new…

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Infections, Public Health, Vaccines, viruses on May 13, 2014

Unless you’ve been living under a rock (and even if you have) you can’t help but have noticed the headlines about all the viruses we’re seeing lately. Measles in Ohio – the largest outbreak in the US since 1996. Polio in Syria and Iraq – a resurgence of a once eradicated virus as war leads to a breakdown in the vaccination efforts. MERS – a second case reported in the US of a “new” zoonotic infection from the Middle-East.

There was a whole session devoted to these “emerging” infections at the recent Pediatric Academic Societies meeting in Vancouver. There are many lessons that we can take away from these events. Firstly, that the well-fought victories we have won against vaccine-preventable infections are actually more of a fragile truce. Given enough of a susceptible population many of these viruses are ready to recur. Measles is an obvious example: probably the most infectious disease known to man, and a plane ride away from ongoing outbreaks in Europe and Africa. One of the most embarrassing exports from my homeland of England has to be the disgraced Andrew Wakefield (I won’t do him the honor of calling him a “doctor”) who pedaled fabricated data to support his efforts to sell a “safe” measles vaccine to a fearful British public. But what about polio? For the first time in years we have seen a significant increase in cases worldwide, as the safety of those administering the vaccinations has been threatened by war. Even as India can now claim itself Polio-free for the first time, I’m starting to wonder if and when we might expect our first case of imported polio to the US from the northern African countries or the Middle East, as the vaccine delayers and refusers leave us with an increasingly vulnerable population.

Secondly, that the pathogens just keep on coming! The Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome virus is a coronavirus, only the sixth known to infect humans. It is entirely distinct from the SARS coronavirus, and we’re still trying to piece together exactly how humans are catching and spreading it. Thankfully human-to-human transmission seems to be inefficient, which is just as well as asymptomatic infection seems to be rare, and the mortality rate is about 40%! It’s just as well it has absolutely nothing in common with a virus that causes the common cold that could mean its transmission might become easier…oh, wait….never mind….

The third lesson I took away from the PAS meeting was just how adept we have become at chasing these infections down. Modern sequencing technologies allow us to send patient specimens from an outbreak of an unknown infection, and within a few days we can have a full-length genome sequence and a phylogenetic tree of its nearest and dearest. MERS was isolated in good old fashioned virus culture by a doctor in Saudi Arabia, then confirmed through collaborative efforts in the UK and Netherlands, and reported publicly through global mailing lists prior to publication. Infectious Disease doctors and epidemiologists are recognizing the ease of global spread of infection, especially novel infections, and the need to work together if we are to stay ahead of them.

But it’s not just exotic imports we have to worry about. The epidemiology of infections in the Americas is changing too. Florida has already become a place where Dengue fever can be picked up without the need for a passport, and as our climate changes that may change too. I saw three cases of imported Dengue in Connecticut last year, and all we need is the Aedes aegypti mosquito to set up shop here and our imported cases can become local! (Chronic Dengue in Connecticut, anyone?)

Just about the only positive thing to come out all of this, is that it’s pretty much guaranteed that my job will stay interesting for years to come.