How safe vaccines led to the resurgence of pertussis

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Antivax, Children, Public Health, Vaccines on August 21, 2012

For those who haven’t been under a rock recently, several parts of the US have seen a surge in pertussis cases. Much of this has been (fairly) blamed on anti-vaccination efforts to reduce herd immunity and the cocooning of vulnerable infants. But that’s not the whole story.

Interestingly enough, it’s now clear that the DTaP vaccine (diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis) doesn’t provide long-lasting immunity. We had some clues with this as an awareness grew of pertussis in older teens and adults, fueled in part by vastly improved testing for pertussis (PCR versus ‘cough plates’ for culture) and a recognition that pertussis in older kids and adults didn’t look like the classic ‘whopping cough’ that youngsters got.

A booster dose of pertussis vaccine was recommended, included as part of the tetanus booster (the new Tdap vaccines). Recent outbreaks seemed to focus on the group of kids aged 10-11 years of age – when vaccine immunity was waning, but just before their Tdap booster – but the recent outbreak in Washington State has involved even 13-14 year olds, who did get their booster!

The question then should be – why does the NEW vaccine work LESS well? The answer is because it is SAFER.

The old DTP vaccine began to get a bad reputation for neurologic disease – in fact a contraindication still exists to withhold pertussis-containing vaccines in kids who develop neurologic issues after pertussis vaccination, even though the vaccine is different. The old DTP contain literally thousands of antigens, based as it was on a relatively impure cocktail of cell culture fragments that contained the pertussis bacteria. It caused a fair amount of immune reaction, and clearly was linked to febrile seizures.

Several high-profile cases of apparently neurologically damaged children (leading to the formation of some of the early modern anti-vaccine movement) pushed the vaccine manufacturers to create a cleaner vaccine, an ‘acellular’ pertussis vaccine, which is why we have DTP and DTaP. DTaP doesn’t have the same link of febrile seizures and no link to any neurologic issues (interestingly, as detailed in Paul Offit’s book on the history of antivaccine junk science, neither do any of the original DTP kids…it was all a big screwup). Tdap is even less immunogenic as it has slower concentration of antigens – you can tell this because it has a small “p” instead of a big “P”. True story.

The trouble of course is that by having a less inflammatory response, with far fewer antigens, the protection is less. The original DTP vaccine contained more antigens than the ENTIRE modern vaccine schedule does, several times over. Any statement about ‘too many too soon’ is pure bunk – our kids are exposed to fewer vaccine antigens in their entire schedule that we were in one vaccine.

This story highlights several points – firstly, contrary to antivax propaganda, not only are there mechanisms in place to detect and respond to potential vaccine side effects but there are CHANGES made to the vaccines in an attempt to keep people safe. (Probably the only positive thing to come out of the antivax movement is the establishment of the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, VAERS). Secondly, there are compromises to be made – more effective sometimes also means more side effects, so if you want to lower one you may end up lowering the other.

There is also data from Europe that as the vaccine strains of pertussis wane, there is strain replacement with potentially more virulent strains. So although we are seeing fewer cases, those cases we do see may be more serious (this finding hasn’t yet held true for the US…as far as I know).

Of course the antivax brigade have twisted the story yet again “Whooping Cough Epidemic Caused by Virulent New Pertussis Strain—And It’s the Result of Vaccine” shouted one headline. While technically true it doesn’t really go into the real explanation of WHY…even more impressive, but entirely unsurprisingly to me, the actual article the antivax site uses to support their claim starts with the words “Before childhood vaccination was introduced in the 1940s, pertussis was a major cause of infant death world- wide. Widespread vaccination of children succeeded in reducing illness and death.” which not only proves how disingenuous antivax proponents are, but how stupid they are. The first rule of selective quotation is to use sources that support your argument.

Sadly, those who believe antivax propaganda are not usually stupid – if anything they tend to be more educated than average, and well read. They just read the wrong things. Not everyone can go to medical school after all.

Then again, even that isn’t foolproof. One of the original antivax “Expert” witnesses from the UK trials that showed the DTP link with neurologic illness to be wrong went on to further his infamy with AIDS denialism.

Much of the details on the stories of the DTP and DTaP history are in Paul Offit’s book – Deadly Choices, which I highly recommend. In it he not only details how antivax proponents twist science and the facts to suit their case, but also how they nearly brought down the entire US vaccine industry through irresponsible and indefensible litigation. The vaccine WORKS to reduce serious illness from pertussis and undoubtedly saves lives. It’s not perfect, no one has ever said a vaccine was perfect – at least, not unless they were trying to make a point that it wasn’t…

Counterintuition – why neonatal herpes turns logic on its head

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Children, Guidelines, Infections on August 9, 2012

“No maternal history of herpes”

When dealing with a newborn baby with a fever, those are words that strike fear into my heart.

Wait, what? You said no maternal history? Yep, that’s right.

Neonatal herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a topic that is full of counterintuitive statements, and far too much confusion. The wrong people get tested, the wrong people get treated, the wrong babies get worked up aggressively. When other docs diligently rattle off the “pertinent” aspects of the maternal history and clinical examination of the baby, in my mind I’m mostly saying “Don’t care, don’t care, don’t care….” before I interject and ask about test results that often haven’t been ordered.

Based purely on a numbers game, thanks to things like vaccination and Group B Strep prophylaxis, many early onset infections in newborns have been reduced. There is simply less infectious disease hanging around. But as a result, viral infections like neonatal herpes are proportionately becoming larger players – in some hospitals it is as common as bacterial meningitis. And neonatal HSV is a killer.

HSV comes in three distinct flavors – the least lethal is skin-eye-mucus membrane (SEM) disease. This is how many people expect to see herpes – a rash, typically vesicular (clear fluid-filled little blebs) and maybe some eye discharge or mouth sores. Most pediatricians, if they see something like this, appropriately freak out a little bit. SEM disease by itself isn’t too dangerous, and if treated properly is almost never fatal. Herpes is tricky though – in babies it can mimic other rashes, so you really do need a low threshold to consider it. ANY neonatal rash that doesn’t fit a normal neonatal rash (so know your neonatal rashes!) deserves a workup. There is nothing more sobering than to run a case of a neonatal rash by an ID doc and to have them tell you with complete sincerity that “You can save this baby’s life. Get them to an ER. Now.” Untreated SEM disease can progress to infection of the brain.

The most obvious presentation is disseminated disease – which weirdly enough can occur before SEM disease…first week of life or so. The kids are sick – really sick. They can be in shock, bleeding, in liver failure and struggling to breath as the virus overwhelms pretty much every organ system. The problem here is that even faced with this situation bacterial infection is considered immediately, and herpes can still be overlooked or thrown into the mix as an afterthought. Again, good neonatologists and pediatricians will be all over this from the start, having experienced their share of disasters in the past. Disseminated herpes is mostly fatal without treatment – and even with therapy about a third will still die, many of the survivors left with significant disabilities.

The last type of herpes infection is of the brain. Typically presenting later in the neonatal period (3-4 weeks of age, rarely later) herpes encephalitis of the newborn is devastating. Herpes causes a hemorrhagic encephalitis, meaning that it chews your neurons up into a bloody pulp. To a brain that has barely begun its developmental process, this is a disaster. Even if the baby survives they may be blind, deaf, paralyzed or have significant developmental delays.

From how I describe it above you might assume it would be easy to spot these kids. Well, it is – once it’s too late. The success of treating HSV depends to a large extent on how quickly you can start acyclovir – one of the few medicines we have that can treat viral infections (it’s pretty much only used for HSV). Acyclovir can shut down virus replication, but does nothing for those cells already infected. The difficulty with HSV lies in the nuances of the medical history.

Let’s try some armchair science for a bit. Would you, as a baby, rather get HSV from a mother who is having a recurrent outbreak of HSV, with low-levels of virus, and have her give you antibody protection through the placenta…or would you prefer to catch HSV from a mother who is having her FIRST outbreak (which may be without symptoms) with high-levels of virus and no antibody protection? Well, you may ask, how likely is that? The answer is Very. About 90% of all neonatal HSV cases come from mothers with no history of HSV. If your mom DOES have HSV and has a recurrent outbreak, the risk of transmission is about 5%. For a new case – its closer to 50%. Maternal history of HSV is relatively PROTECTIVE for the baby.

But the focus is on the mothers who test positive for HSV during pregnancy. They get put on valtrex (an oral version of acyclovir which is well absorbed), when it has not been shown to sufficiently reduce transmission. They may get a C-section, when that hasn’t been shown to help either (except maybe in the case of active lesions at the time of delivery…and even then it’s unreliable). The mothers who are HSV-negative are ignored, when they are those at highest risk of passing HSV to their babies. In an ideal world, their sexual partners should be tested and if THEY are positive THEY should be put on valtrex to reduce outbreaks and educated about the risks. But the fathers aren’t the patient….so nobody does that.

A big myth about HSV is that all babies with it look sick. Well, they do eventually – but to start with they look pretty normal. I have heard docs say that a baby looked “too good to tap” – meaning they didn’t perform a spinal tap to check for meningitis or HSV encephalitis. Or they don’t test sufficiently for HSV, or don’t start treatment with acyclovir while test results come back (these same babies are almost universally started on antibiotics for presumed bacterial infection). Published case series of proven HSV cases shown over and over again that babies with HSV present with relatively innocuous symptoms. “poor feeding” “fever” “sleepiness” before the more obvious symptoms of “shock” “seizure” or “respiratory distress”. Remember, by the time the baby is sick from HSV the damage has already been done, and you can only try to stop it from getting worse and hope the kid recovers. With bacterial infections we can kill them directly with antibiotics and the damage is usually secondary to the infection, and not because the bacteria are literally eating up your cells and blowing them apart as HSV does. Even with successful treatment, symptomatic HSV in babies has a slow recovery.

So how do you deal with this uncertainty? You can’t trust the mothers history, you can’t trust the baby’s physical examination or symptoms…what do you do?

My approach is to have a low threshold for suspecting HSV in neonates. ANY baby getting worked up for a possible bacterial infection needs to have a workup and empiric treatment for HSV as well. Babies with weird symptoms (especially rashes or neurologic symptoms) need to have HSV considered FIRST, before bacterial causes. HSV is not only potentially devastating – its treatable, and therefore the bad outcomes are preventable.

Fortunately the Committee of Infectious Diseases of the American Academy of Pediatrics has published recommendations – albeit in a rather inaccessible set of paragraphs. I can summarize them here though:

Spinal tap for HSV PCR of spinal fluid.

Liver enzyme testing for disseminated disease – chest x ray if respiratory symptoms.

Surface cultures from eye, mouth, rectum and any skin lesions.Start acyclovir – do not stop until all tests are negative.

Do ALL of this this for EVERY BABY with suspected HSV.

Repeat spinal tap on kids with positive CSF to ensure clearance after 21 days – continue therapy if still positive.

A big mistake I see people making is in testing the spinal fluid to “rule out HSV” but do not doing the rest of the workup. Spinal fluid testing for HSV no more rules out SEM or disseminated disease than a urine culture can diagnose meningitis. I have seen cases missed (or nearly missed) because someone didn’t do the whole thing. You NEED the liver enzyme testing to rule out disseminated disease, and it matters. Treatment for simple SEM is 14 days – treatment for disseminated or CSF disease is 21 days. I have seen a handful of kids with positive CSF tests but with totally normal looking spinal fluid (eg no white cells, normal protein levels etc).

The trouble is HSV, as bad as it is, isn’t all that common among the hundreds of kids you will see with suspected neonatal infection. And many of THEM will be obviously HSV. So many kids get a semi-workup and we get away with it because “whoops, the CSF is positive!” and you treat for 21 days even though you didn’t check the liver enzymes.

But I’ve also seen the opposite – kids who were partially worked up and the diagnosis was missed, or delayed, or the severity was under-appreciated. All too often the “standard of care” let’s these kids slip through the cracks – which is inexcusable in my mind when there are experts who put it down in writing exactly how to work up these cases.

So let’s raise the standard.

Totally useless history:

Mom has no history of HSV

Mom got Valtrex

Mom got a C-section

Baby looks well

REAL risk factors for neonatal HSV:

Prolonged rupture of membranes

Active lesions at time of delivery

NO maternal history of HSV

Prematurity

Age less than 21 days

Unusual rash

Seizures or lethargy

“Sepsis” not responding to antibiotics (oops! too late! – better call your lawyer…)

Testing

CSF PCR

PCR/Culture of skin lesions, eyes, mouth, rectum

Liver enzyme testing

Chest X ray (if symptomatic)

Treatment

Acyclovir 20mg/kg/dose IV every 8 hours

Until all tests are negative (typically 2-3 days empirically)

14 days for proven SEM disease

21 days for disseminated or CNS disease

And if you’re not sure…get a consult…

Consult or curbside?

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in EBM on June 21, 2012

As a consultant my expertise is sought out in largely two ways – a formal consultation (a request to see a patient, obtain a history and perform a physical examination, review laboratory tests and recommend further evaluation or treatment), or a curbside question (a quick hypothetical or general question with the expectation of a simple answer).

An example of a curbside question might be “How many pneumococcal serotype responses would you expect to be normal in an immune evaluation..?”. The answer is 5-10 depending on the age and immunization status of the child, but in reality the correct response is “why the heck are you ordering an immune evaluation on a kid that I know nothing about…?”. The indications for performing an immune evaluation (frequent or unusual infections) are generally the sort of thing an Infectious Disease specialist should have been consulted on!

People often start a curbside question with “This isn’t a consult, but…” as if a consult is a bad thing. It isn’t. A consultation isn’t an inconvenience, it’s what I get paid to do (salaried or not, divisional revenues ARE based on the consults I get called to see). It’s what I ENJOY doing – if it wasn’t I wouldn’t be in the job in the first place. And even if I AM busy, tied up in clinic, or off-site taking call from home, it’s in the patient’s best interest.

No matter how well you quiz someone over the phone, there is no way they can adequately convey the entire medical history and physical exam, the concerns of the patient and family, trends in lab values, recent antibiotics and other meds, and the simple gut vibe of a case… A complete consult, done properly, can take up to an hour and may involve field trips to radiology and the micro lab to check things out for yourself. That is a considerable chunk of time (certainly more than a curbside question) but the value of having a subspecialist see the whole picture cannot be overstated.

The dangers of answering a curbside about a specific patient are legion – you may miss drug allergies or interactions, co-existing diseases or subtle clues in the history or exam that would point towards a specific diagnosis, you will tend to overtreat “just in case”, lacking the reassurance of seeing the patient for yourself, but may just as easily undertreat an infection that had been missed or misdiagnosed. Worse, for the consultant, chances are good that their name will end up in the chart “case discussed with ID”, which medico-legally puts us in a bit of a spot. Then the onus is on you to show that you had no medical obligation or responsibility to the patient should something bad happen…a hassle and horrific waste of time at best.

The other issue is “added value”. Even when I’m called to answer a specific question, I almost always end up offering something else. If I’m asked about best treatment options, I will offer alternative diagnoses. If the question is what this disease could be, I will recommend empiric therapy as well. Every consult is a teaching opportunity, whether about a specific disease or a general bit of advice on ID. For THAT patient I want the docs who consult me to know as much about the disease as I do.

That’s all in theory – what about the evidence? One study of mandatory ID consultation for outpatient IV antibiotic therapy found that 39 of 44 patients had a change of therapy (!), meaning that 88% of the time the current plan was not ideal. 39% of the patients were sent home on oral instead of IV antibiotics, 13 patients (30%) changed medications, 5 patients changed dose, 3 changed planned duration, and 1 patient was stopped entirely. Cost savings were $500 per patient EVEN TAKING INTO ACCOUNT THE CONSULT FEE. In Germany and the US, ID consults have been linked to significantly reduced mortality from staph infections. In Italy, formal ID consultation on ICU patients reduced cost, mortality, ICU stay, length of mechanical ventilation – all due to improvements in antibiotic usage. A financial analysis of curbside consultations suggested that close to $94,000 in revenues were lost in a year by giving advice over the phone without performing (and billing for) an appropriate level of consult. With antibiotic cost savings and increased revenues to the hospital, consults really are a win/win situation.

So what’s really happening when you say “This isn’t a consult, but…”? You’re putting your patient at risk of being treated for the wrong diagnosis, or being wrongly treated for the right diagnosis, you’re increasing hospital costs and increasing patient mortality, and you’re passing up the opportunity to learn something yourself. It’s not good medicine – it’s not good for anyone.

Say it after me: “I’ve got a consult for you…”

This post may or may not have been inspired by the fact that I have had an inordinate number of consults this week which started out as curbsides that would have led to inappropriate care….

Learning your lines

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Bacteria, Guidelines, Infections on May 28, 2012

I was recently asked “what is a line infection?” and I realized that it would take more than 140 characters to explain everything about it. I also figured it would be a good topic to educate on, since as a whole line infections are very badly managed.

Briefly, a line infection refers to a bacterial (or fungal) infection of a central line, usually in a vein but an arterial line could get infected too. The classic case is a catheter tip infection with bacteria in the bloodstream. The patient may have a fever, and may be quite sick indeed.

One might ask; “How the heck does that happen??!!”. Actually, surprisingly easily.

Lines can be infected from two ends – the outside end is open to the air and is accessed every time a medication or IV nutrition is put through it. If sterile technique is not used bacteria can get into the line. Heck, even with sterile technique bad luck plays a part too. These bugs are often skin bacteria that are normally fairly wimpy or considered “contaminants” when grown in blood cultures (meaning they were picked up from the skin as the needle went in, not that the lab contaminated them!). The inner end is safely inside a blood vessel, which is sterile, but if bacteria get into the bloodstream for other reasons they can stick to the plastic line, since bacteria as a rule LURVE to stick to non-biologic stuff. These can be any kind of bug, but are more likely to be bacteria from the gut who wandered off accidentally in the bloodstream and find a home there before the immune system can kill them off.

Once a line infection is established, we have a problem. Plastic lines have no bloodstream and no immune system. Bacteria can produce slimely stuff (called a biofilm) that coats the infection and acts as a barrier to the immune system, and some antibiotics. Imagine smearing peanut butter on a table, then trying to get it off with your finger. Even after a good swipe you’ll leave a smear behind. Now imagine trying to clean it off by dripping detergent onto it. That’s what it’s like trying to clear a line of a line infection. The only way to guarantee clearing a line is to pull it out and put a new one in.

Pulling a line is not a lightly-undertaken job though. If someone has a line they probably have a reason for it – long-term nutrition, chemotherapy, antibiotics etc. If you pull that line you may interrupt their usual doses, for days at a time. Line sites get scarred and if you do this enough you can run out of new sites to use! So it’s paramount to diagnose a line infection properly.

Imagine the following: a kid with a line gets a fever. They come to the hospital and blood cultures are drawn from the line. They grow a staph aureus. OH NO! He has a staph aureus line infection right? Not necessarily. Blood drawn from the line is just blood – this could be any other staph bacterial bloodstream infection, such as from a bone or joint infection, endocarditis (infection in the heart) or something else. We need to know whether the line has more bacteria than the rest of the blood stream.

This is where most people go wrong – you MUST MUST MUST draw multiple cultures, including a culture from some place else (and yes, this means sticking a needle in someone – suck it up). Ideally you need quantitative cultures, where you draw a fixed volume of blood then plate it out and count the colonies. If the line cultures grow significantly more than the periphery, it’s a line infection. If it’s the same, it is a bacterial bloodstream infection, but not a line infection. BIG difference. If you can’t do “quants” you can time how long the cultures take to turn positive in the lab. Most experts consider a difference of a few hours to be significant.

Once you know it is a line infection, you can think about what you’re doing. Most people get started on broad-spectrum antibiotics to cover all the likely bacteria. Once you know your bug though, you can tailor therapy. Non-Aureus staph for example may actually be cleared using a couple of weeks of antibiotics. Enterococcus or staph aureus are tougher, gram-negative bacteria from the gut are even worse. Pseudomonas or candida/other fungi are practically impossible to clear, don’t even try.

What’s the harm in trying? Time. You waste time. You have a kid sitting in the hospital getting IV antibiotics. You may send them home…and you may be able to show that the blood cultures turn negative….but you stop those antibiotics and WHAM the peanut butter smear you didn’t quite clean off has grown back into a big old dollop of yuck again. You’ve wasted 2 weeks at least, several days of hospital time AND now you’re back at square one and you have to pull the line you should have pulled two weeks ago.

The two biggest errors I see people try with line infections are: not correctly testing for line infection with sufficient blood cultures; trying to salvage an unsalvageable line. People are fooled into thinking they have cleared a line infection, when in fact they may have been treating a bacteremia from another source and just THOUGHT they were treating a line infection. This reinforces the incorrect belief that clearing line infections is easy…

I get consulted on these kids. I can rarely offer specific guidance unless the correct workup has been done. I have seen kids get lines out that I am sure were not infected, and I have seen kids treated for weeks for an infection that could have been cured with a 30 minute procedure to pull the line out. There are evidenced-based guidelines on this issue published by the Infectious Disease Society of America – ID docs KNOW how to manage line infections – and yet our guidelines, and our specific advice, is often ignored.

Best reason I was ever given for not removing an infected line? “We can’t take it out, we’re using it for the dopamine”. Yeah, well maybe if you stopped using it the patient wouldn’t be in shock any more…

Screenshot of the most critical table from the IDSA guidelines.

The redundancy of being called a “Medical Educator”

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Career, Medical Education on April 20, 2012

Incredibly, since I have been in my new position for over 6 months, this morning was my first lecture (but I use the term loosely) to the residents here. It was ostensibly on “infectious rashes and infestations” – but I entitled it “Nasty skin infections – cos there really aren’t any nice ones”.

It was apparently well received.

I have a knack for teaching. I’m not saying that because I think I have a knack – other people have told me so. I have various awards to show for it. I have people ask me to teach, and I assume it’s not just to hear my awesome accent. It has a history going back to high-school where my friends would ask for help with their homework. I had the annoying habit of not giving them the answers – rather I would try to help them figure it out for themselves – responding to their questions with questions of my own. I don’t remember whether I did this out of a sense of mentorship – the benign guidance of a sage helping them to reach their potential – or out of sheer bloody-mindedness and for my own amusement. I do know I simply didn’t think it was “fair” that I had to figure it out for myself but they wanted the answer simply given to them. I can’t blame them – we all want that at some point.

In medical school I found myself struggling in a competitive, highly academic and esoteric system which I was pretty unprepared for. I remember writing a scathing review of the teaching I had received there for my college magazine. I “dropped out” of one tutorial class to do self-study instead, and brought my grade up two points as a result (on a 4 point scale, that’s not bad…). I laid down the mental framework for how I wanted to be taught, and applied that to others where I could. I was lucky to be asked to supervise (teach, in Cambridge lingo) genetics and virology to two of the university colleges for two years. Ironically I found myself as a flawed part of the very system I had complained about – flawed in that I was teaching without any training in how to teach!

It was in my residency however where I really found a role for myself in teaching. My wife tells me that I “like telling people how it is”. She may be right. In any case, there are ample opportunities for teaching medical students, junior residents, peers and colleagues during the years that you yourself are getting educated and trained in medicine. I developed my own style – honed through trial and error, practice and observation. My research years had taught me a lot about how to teach and how NOT to teach effectively – and also removed whatever fears of public speaking I might have harbored. We all know that “teachers teach how they were taught, not how they were taught to teach”, but I made a conscious effort to TRY to teach using techniques that I knew to be effective, even if I hadn’t experienced them directly. I cherry-picked those I liked and adapted them to my own personality.

The techniques weren’t all that became developed – my repertoire of content grew and was refined. For most of the topics I was asked to teach about I got to the point where I could grab a pen and paper, or whiteboard, and put together an interactive case-based 1-hour teaching session with no notice.

After today’s success I thought a little about my role as a medical educator, and I remembered something.

Doctor. We all know what it means. Or do we?

It means “Teacher“.

The word “Doctor” has been hijacked by the medical profession (and other related careers), where in fact it was intended to mean someone with sufficient learning in a subject area to teach others. Technically in fact, most medical degrees aren’t “Doctorate” level at all, since they are “first degrees” in medicine, regardless of whatever degrees a person may have in another subject. My own medical degree reflects that: MBBChir, Medicinae Baccalaureus, Baccalaureus Chirurgiae – Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery. An MD in the UK (and almost everywhere except the US) is a true post-graduate degree with a research dissertation.

Ironically the medical profession seems to have forgotten that. Medical education in the US is an oft-neglected role, poorly reimbursed, run by those with a passion for teaching while feeding off the table scraps that their procedure-driven peers feed to them through the teaching hospital income. Until recently, there were few real incentives to teach or contribute to medical education – promotion and bonuses were linked to clinical revenues and research grant dollars. I am fortunate to work in one of the (apparently) few places that does place a value on medical education such that I can use it for career advancement rather than a hobby in my spare time. People go into medicine for all sorts of reasons – to help people, to heal, to make money, to do cool procedures and surgeries – but I doubt very many go into medicine to teach.

And yet they carry the title of “Teacher”. My own career track is that of a “medical educator” – which seems to me to be a redundant phrase, if you think about it. The fact that we have to label medical educators as something special shows how we have drifted away from the true meaning of “Doctor”.

To go back to our roots, we should ALL be educators. Every year there is a wave of students leaving their education and entering training, and a wave of residents leaving training and entering the real world. These men and women need guidance. Beyond the academics and pearls of wisdom, they need mentoring, career and business advice, insight into work-life balance and their options beyond the ivory towers. They need to know how to recognize meningococcemia, but they also need to know how to get a parent to recognize it over the telephone. They need to know when to admit a patient, but also how to bill for that admission. They need to know how to convince a skeptical teenager of a treatment plan, and how to negotiate a partnership contract.

Physicians don’t have to work at a medical school to teach – they can contribute to career fairs, social media, newsletters, take on elective students in their practice…anything is possible. There are literally hundreds of thousands of years’ of experience out there waiting to be tapped…

So I urge my medical colleagues – reflect on this. Remember your title, your role in history and the potential you have for leaving a legacy of medical practice in your wake, in the form of the next generation of Medical Doctors.

As Hippocrates himself said:

“…I will impart a knowledge of this art to my own sons, and to my teacher’s sons, and to disciples bound by an indenture and oath according to the medical laws…”

Healthcare as a Right?

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Uncategorized on January 31, 2012

Firstly I want to preamble this with the fact that I’m obviously biased. I was trained in a national health service and I’ve spent my entire medical career in an academic medical center, somewhat sheltered from the pressures of medicine as a business and surrounded by Docs who certainly didn’t go into medicine for the money. No-one in Pediatrics does it for the money… So my impression of how a Doc should think about medicine and patients may not jive with everyone else’s. That’s fine. But I did want to put down my thoughts on healthcare as a part of society – how we should think of it, and therefore how we should pay for it. My opinions at least have a lot of facts to back them up, in fact I have these opinions BECAUSE of these facts – there is simply no other way I can interpret them.

One of the most contentious parts of the United States Affordable Care Act (healthcare reform, the misnomer “Obamacare” or whatever you want to call it) is the “Mandate” – the requirement that everyone needs to purchase some form of healthcare insurance, or pay an additional amount on their income tax return. What this does is bring the US in line with every other developed nation in having universal healthcare (coverage for all its citizens). The existing systems of Medicare (for the Elderly) and Medicaid (for the Destitute – the only way I could keep them straight as an outsider) have huge coverage gaps, and healthcare costs are the leading cause of bankruptcy in the US. This is embarrassing. Or at least, it should be.

Instead, there is a prevailing view among many that “The US has the best Goddarn Healthcare System in the World!” and any attempt to change it will drag it down.

Hardly.

The US is 38th in the world ranking for life expectancy. Cuba is 37th. EVERY other major industrialized nation ranks higher. And they all have universal healthcare. Childhood mortality in the US is also at the bottom of the pile. The WHO rates the US as 1st in terms of in cost, 1st in responsiveness, 37th in overall performance, and 72nd by overall level of health.

Despite these mediocre results, the US pays more than anyone else. In fact the healthcare spending in the US is almost TWICE that of anywhere else, with the exception of the island nation of Bermuda where it’s about the same.

So something dramatic has to be done, of that all sides agree. But why are there even sides? What are the arguments for and against universal healthcare, or in other words to consider healthcare as a right?

The Golden Rule

“Treat people as you would like to be treated.” Since I love the fact that I don’t have to worry about catastrophic medical costs, and my employer pays for most of my medical insurance, I think it would be awesome if everyone had that. It has made headline news for years, how many millions of Americans are uninsured and as a result decline healthcare (or leave it too late) since they can’t afford it. The issue is compounded since those who are in good jobs (and could afford to live without insurance) already have health insurance, typically heavily subsidized by their employer – so they may only see 10-25% of the actual premiums. For those without this luxury, or those who were in a job but lost it and had to pay COBRA to extend coverage, the true price of healthcare premiums is shocking. This simply exacerbates the healthcare divide. Medicaid will pick up the pieces for the very bottom of the pile, but there is a big chunk in the middle who don’t fit. It is only humane that everyone gets the same opportunity, regardless of income or employment status.

If you disagree with that, then you’re basically saying that some people don’t deserve to have access to good healthcare. That’s mean, and probably morally indefensible. Who actually WANTS another human being to be sick?

The insurance companies

Oops, was that bad word placement? No, not really, but sometimes it does seem that way. I have lost count of the number of times I have had to fight with insurance companies to get approval for a test (!) or treatment for a life-altering or life-threatening diagnosis. Insurance companies are not there to pay for your healthcare – their agenda is profit, and they will do anything they can to deny payment since it hurts their bottom line. If their agenda was patient care, they wouldn’t fight these fights. The documentation that goes into justifying reimbursements is crazy. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was targeted primarily AT the insurance companies, since Congress effectively gutted the ability of the bill to do anything else more meaningful. What it basically said was “You can’t ‘Not cover’ someone because they’re sick, you can’t stop paying because people get sick, preventative healthcare should be 100% covered, and you have to allow kids on their parent’s plans until 26”. This targeted the most vulnerable people – those with serious or pre-existing illnesses who would be excluded from plans (to help the bottom line) and young adults who weren’t in jobs with healthcare benefits. However, there was an issue here. If you add all these people onto the list, you WILL increase payouts. That is inevitable. Little Sally’s chemo for her leukemia doesn’t some cheap… You need a large number of non-claimants in the system to keep things reasonable, and this is where the Mandate comes in (my initials, for emphasis). If everyone is on board, revenues can keep up better with the payouts. Simple math. Since it is only humane and humanistic to want everyone to be healthy, everyone has to be in the game. Everyone needs to be covered.

The Mandate

The Mandate is nothing new – Govt has imposed mandates on all sorts of things – they’re called “Laws” – for hundreds of years. There have been efforts to Mandate healthcare coverage going back to the Founding fathers, from the Left and the Right. This should be an issue that has no party lines – and yet here it does. Why? The biggest criticism is individual choice. There is no choice about it – well, there is, but you then have to pay more on your tax return. Hey, that seems unfair…what if they can’t afford it…? Well the ACA establishes insurance markets to help individuals purchase plans more fairly, it sets up a special plan for patients with pre-existing conditions, AND if you’re low-income the plans are subsidized AND the penalty is reduced, or even waived. Bottom line – no-one should be on the hook, at least no more than they are now! However, this is a hodge-podge approach. People can still opt-out, and pay the fine (which incidentally, is used to reimburse the healthcare system when they DO use it as an uninsured patient…) and religous-political restrictions have been placed on certain plans in the exchanges carrying abortion coverage. (Wait, wasn’t there a separation of Church and State in the US…never mind).

But the funny thing to me is that either (A) You already have coverage and aren’t affected by the mandate, or (B) you don’t have coverage and WILL GET HELP GETTING IT. It’s a win-win. Who DOESN’T want healthcare coverage? Do you really want to exercise that right, put yourself (and your family) at risk of massive financial losses AND put the rest of society on the hook for your bills when you can’t pay up? Hardly fair. There is an element of social responsibility here. The Mandate isn’t the Government forcing you to do something that is solely about individual choice, it’s helping you do something that is frankly irresponsible of you NOT to do. Personal choice is only ok so long as it doesn’t impact others, whether you intend it to or not. At some point, personal choice is NOT ok – and as a society we decide where that line is drawn (see next section).

Some (myself included) have argued than a mandate to purchase some kind of insurance is nothing new – think of car insurance after all. Others have countered that not everyone has a car, and they don’t have to purchase insurance. Yeah, but since everyone needs healthcare, doesn’t that help the “Healthcare should be a right” argument? Since we all need it, we should all get it, and we all have a responsibility to maintain it.

Social Justice

We all live in a society – be it a tent village in the Amazon or a metropolis like Los Angeles. In that society there are certain rights, and responsibilities. We expect people to treat each other a certain way. As a whole we don’t steal from, rape or kill each other and can go about our lives in a reasonably predictable and productive manner. We expect people to stop at red lights, and we in turn are expected to stop. So how does this fit into healthcare? Well, since it’s morally indefensible to argue that some people are more deserving of healthcare than others, and that in order to provide protection for everyone we have to have everyone on board, THIS is where social justice comes in. If you want to benefit from the system, you have to be part of the system. Since you CANNOT avoid being part of the system (short of moving out of the country), you have to contribute. The only difference between a mandated health insurance bill and a mandated tax is the lettering on the bill. It is money going from you to somewhere else for a service (protection from healthcare costs).

The US needs to think of healthcare differently, since we know that everyone needs it, as part of our social fabric as much as clean water and clean air are. If they are part of the social fabric, we should expect government help to get it, and that means we should be expected to contribute to support it. The US has, mostly, moved out from the days of the Wild West – healthcare seems to be the last frontier to go.

Let’s look at another aspect of American society – we all expect to be able to dial 911 when we’re being burgled, or our house is burning down, and the police and fire department will show up, free of charge to help. The ambulance will show up too if you dial 911…but they’ll send you a bill afterwards. Why doesn’t that strike anyone as odd?

Single payer – the Public Option

This, in most reasonable people’s minds, is really what “Obamacare” was all about. A government health insurer for all. It doesn’t exist. It was stripped from the ACA in order to get the insurance reforms through, so although the ACA went through it lost the most important part of it. Why do I consider this important? What are the advantages of single payer? Well, for starters instead of dealing with the HUNDREDS of insurance companies there would be one. The plethora of billing staff who exist solely to shuffle paper around and sort through this mess wouldn’t exist. Fully 30% of private healthcare dollars is wasted on administration (ie doesn’t reimburse for the actual medical care) whereas for Medicare, one of the US Govt plans, it is closer to 3%. That’s quite a difference. In addition, the public option would streamline the whole “Mandate” thing, avoiding the situation where we are now with a Govt mandate to purchase a private company’s product.

This wouldn’t be Govt-run healthcare, it would be Govt-financed healthcare. Same Docs, same hospitals and labs, much easier reimbursement system. Insurance companies were terrified that a Government-sponsored plan would put them out of business, with its improved efficiency, larger insurer based and no need to kow-tow to CEO’s and shareholders for profits. This is why they lobbied so hard to strip it out of the ACA. That alone should tell you something about the Status Quo and how messed up it is.

Reimbursements

This is where many of the physician complaints are coming from. It is well known that Govt reimbursements are lower than insurance companies’ reimbursements. There is a concern that a single-payer plan from the Govt would hurt Doc’s salaries. It might. But if you can fire all your billing staff that is a smaller overhead to pay for 😀 There are also the issues of Doc’s incomes going to unimportant things like, y’know, massive student loans and malpractice premiums. The fact is, there may not be a great solution here. Short of asking medical schools to stop charging so much, and asking patients not to sue so much, those things are going to remain. Doc’s salaries are high in the US, but aren’t even the biggest part of the problem – drug costs and institutions take a huge chunk too. The pharmaceutical companies and hospitals have their part to play in fleecing the consumer and driving up healthcare costs, which ends up hurting everyone in the long run. One solution is to scrap it all and start again. Another is to tackle one piece at a time, like insurance companies abuses, and work towards a better system. This is what the ACA is all about – one step in the right direction.

My personal opinion is that salaried Docs would help a bit – remove the incentives to prescribe and test inappropriately (you know docs can actually bill more for doing that, even if it’s unnecessary…?). Lower salaries would mean the Docs who were in medicine were less likely to be doing it for profit (instead of for the patients). If we can change the entire mindset of medicine towards it being a public service, and Docs as public servants (rather than a for-profit enterprise) it might help. But this would need massive overhaul from the ground up…and what to do with all those newly graduated docs with loans to pay etc? So much to fix….

Rationing

The “R” word, the big scary “Death Panel” myth, the fear of some nameless bureaucrat controlling your healthcare. Well, it’s already here. Insurers dictate what does and does not get covered, which in turn dictates what your Doc will or will not provide to you. Medical judgment is often not a part of the decision it seems to me – at least, every time I have spoken to a real medical director of an insurer to fight my case they have agreed with me. Every time – which implies they either weren’t involved with the case or didn’t understand it until then. With a finite pot of resources though SOME form of rationing is inevitable. The difference to me is intent – do you want a public service rationing resources so the most needy can access them when they need to, or a private company rationing them to help their bottom line? Do you want a system where the billing requirements of various plans dictate who gets what care, or the same system for everyone?

There will always be a role for private medical care, but basic, life-saving and emergency healthcare should be free. We’re not talking facelifts and tummy tucks on the public purse here…!

The Constitution

Finally I have something to say on whether or not the ACA is Constitutional. Some people have dragged up various aspects of the Constitution (or rather, its Amendments since it needed fixing along the way…) against the Mandate. In the Declaration of Independence (the document through which Abe Lincoln said the Constitution should be interpreted) the following is said:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

It is hard to pursue happiness, be truly free, and ultimately live, without good health. It’s hard to be healthy without healthcare.

That is all.

Links to facts quoted above:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Health_care_in_the_United_States (wiki)

How the Performance of the U.S. Health Care System Compares Internationally, 2010 Update

Insuring America’s Health – Principles and Recommendations (Institute of Medicine)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_health_care_expenditures

I didn’t get the job I wanted…

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Career, Medical Education on September 11, 2011

I didn’t get the job I wanted.

And it rocks.

When I was three years old, I told my family I wanted to be a doctor. My grandparents gave me one of those plastic doctor’s kits – the kind with the flimsy plastic stethoscope in a little white bag with a red cross on it. I’ve told people I wanted to be doctor for as long as I can remember. Aside from brief flirtations with the idea of a killer music career and dabbling in astrophysics (!) it would seem as though it’s been a straight line for me.

But, as any medical student or resident can tell you, it’s not quite that simple. What is classified as “a doctor” varies tremendously. I used to think it meant the doctor I saw for my regular childhood checkups, but then I discovered the exciting TV ER dramas and saw a different side to things. My first “specialty” decision was to be “a heart doctor” – and by that I meant a cardiac surgeon I suppose. My rationale for that was simply that while neurosurgery was more complicated there wasn’t much you could actually fix doing that. It was just cutting things out after all 😛

Then I went on a medical student career conference….and loved the idea of pathology. Sorting through disease causes, an intimate understanding of pathophysiology and anatomy…and really yucky cases. Yeah, that sounded cool.

And then I hit medical school, and somewhere along the way I fell in love with viruses. Bacteria were ok, I guess, but I had a real problem remembering all the damn antibiotics and what they did. My categorization for the cephalosporins consisted of “Cephalo-kill-a-lot”, “Cephalo-cost-a-lot” and Ceph-du-jour”. It was pretty pathetic. I also realized that while surgery was indeed incredibly technical and cool…it consisted of a lot of standing up or running around…and I liked to sit down. I also had difficulty putting things back together after I had taken them apart, something which I understand is a prerequisite to being a competent surgeon. So…medicine it was for me.

But then what kind? Kids didn’t like me – I would walk down the street and make them cry. Maybe I had some kind of weird expression on my face – I never figured it out. But old people didn’t get better, at least in the hospital. Each admission added another diagnosis to the list, and the slow downward spiral was a constant reminder of my own mortality. A selfish thought perhaps, but a valid one when it comes to job happiness. I was in a bit of a quandary.

And then what about teaching and research? Well, I did like teaching, so that would be nice. I had some practice at that during my PhD years. But I had been told that “Those who can, do – those who can’t, teach.” I wasn’t sure I wanted to get lumped in with that.

And as for research – well, I really like bench research. Don’t ever call it “basic science”. It’s not “basic” – it’s actually quite complicated 😉 I remember several people telling me that with the mix of PhD and MB I could go into clinical trials. I pooh-poohed the idea, since I didn’t want to work for the evil money-grubbing pharmaceutical companies. I wanted pure science.

I gradually found myself gravitating to an outpatient office-based way of life. General Practice or Psychiatry interested me – treating the patient instead of the disease (but wait, didn’t I like pathology…? How did that happen..?) Maybe I just liked to talk a lot. I dunno. In any case, at some point when I was planning on moving to the US I sent an email to a pediatrician here – a contact of my wife’s family. He replied that he couldn’t help me with psychiatry or family medicine (as it is called in the US) but I could come over for an elective.

I rather cunningly selected Pediatric Infectious Disease as my rotation, since I would get to work with him. It turned out well. At the end of it I was offered a research job with him for a year, while I worked on the USMLE exams. His boss, the division chief, asked me if I wanted to do clinical trials work. Torn between my thoughts about Big Pharma and my future job prospects…I said yes.

Fast forward 7 years. What did the medical student who didn’t get on with kids, hated antibiotics, didn’t want to do clinical trials and who loved bench research end up doing?

Here I am, an Attending in Pediatric Infectious Disease. In charge of, of all things, an antibiotic stewardship program. I have taken part in over a dozen clinical trials for pharmaceutical companies, and not done any real bench research since I left the UK. I have created a new curriculum and won awards for teaching. My first week on service as “the real thing” has been at times stressful, busy, fun frustrating, but at every step of the way IT FEELS RIGHT. This is what I feel I am meant to be doing.

The bottom line is that whatever you think you want to be, you never can tell where life will take you. Keep your options open and give things a try. Even a couple of years ago the idea of heading up a stewardship program wasn’t on my radar. Who knows what the next 5 years will bring…

Oh yeah, and kids smile and wave at me in the street now. I still don’t know why.

Nearly done

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Career, Children, Medical Education on September 5, 2011

I’m awake.

It’s early.

I don’t have to be awake, but I can’t sleep. You see, this is my last day of service.

Not my last day of work – no, I have that tomorrow – but for whatever reason my mind is aglow with whirling transient nodes of thought (Blazing Saddles reference for you) and I can’t get back to sleep. I’ve just caught up with some outstanding dictations (outstanding in that they are late, not that they are in any way good) and so I thought I’d reflect a bit.

I’ve been at Upstate for the past 7 1/2 years. I showed up here as a medical student, post-PhD, not yet done with my medical training and not yet certain about even doing Pediatrics as a career. I had set up a month-long elective in Pediatric Infectious Disease because (A) my one and only US medical contact was a Peds ID faculty member and, er, that was it. I figured I should brown-nose a bit.

No seriously, that was it.

At the end of that month I had somehow got the next 7 years all planned out… This guy hired me to work for him doing research and clinical trials for a year. I took my USMLE exams. I applied for residency (Upstate was the only place I applied to). It was taken for granted that I would transition into the ID Fellowship, which I did, so I have just been part of the furniture here for all that time.

I have seen the new Children’s Hospital grow from a mythical idea to scaffolding to wonderful newly equipped spacious rooms. I have supervised medical students, watched them grow as Residents and young people, and seen them graduate and start work as Faculty. I have made mistakes, learned a lot, learned that I have a lot still to learn, and I like to think that somewhere along the way I saved a few lives. I’m not sure I’ve actually achieved anything quite so grand – but I’m pretty sure I had a positive impact on an awful lot of kids.

I certainly can’t claim to be the world’s best resident – I have had plenty of peers and colleagues who were better doctors than me: more knowledgeable, more intuitive, harder working, better at getting IV’s started…but I have found that I am good at what I do. I am good with patients and families, I actively practice patient-centered care, I can teach effectively and I can do research. Give me a database and a few hours to code and I can churn out some cool stuff.

It’s a weird feeling to move on – to a job where there are things to get done, where I won’t have the kind of supervisory backup that I’ve enjoyed as a trainee, but where I’ll also have the freedom to practice medicine and work more along my own path. The light at the end of the tunnel has turned out to be an oncoming express train…and I don’t think it truly hit me (pardon the expression) until the past few days. My last 2 weeks of service have been too busy to think about it! Now suddenly, here I am, wrapping up my last dictations and preparing my last lecture. I need to bring boxes to my office to empty it: how weird is that? There are an awful lot of really, really cool people I’m going to miss at Upstate. Nurses, lab techs, pharmacists, Docs – so many people who I’ve worked with over the past few years and got to know. They shaped how I practice medicine. I think that may be the most intimidating thing about having to move – having to re-learn all the ways and intricacies of a new system, a new place. I’ll be flying blind for a bit. I figure it’s worth it.

The thing to remember, and this is a crucial thing for any aspiring doctors to realize, is that I really enjoy what I do. Whatever fluke of fate brought me to Upstate and Peds ID, I can truly say that I don’t think I’d be happier doing something else. Pediatrics wins over any adult care for me, every time. And Infectious Disease…? There’s just something about finding a cause for a disease and killing it. You can’t do that for hypertension, or asthma, or obesity, or diabetes – “You’ve got the bugs, we’ve got the drugs” became my catchphrase.

Confucius said “If you love your job, you’ll never work a day in your life.” He was right.

The art of fighting without fighting

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Patient-Centered Care on August 20, 2011

At a recent ethics conference, where we were debating whether or not to treat a particular patient (medically indicated and life-saving, but against their wishes) a concept came up as one argument to treat. I’m paraphrasing but it went something like this:

“We’re Doctors, and we’ve been trained to treat, so surely we have to do something?”

Now I’m someone who generally abhors people who don’t do their job (or worse, make me do it for them). One of my mantras is JFDI – Just Frickin’ Do It. But this concept was to me a little extreme, and maybe went to the core of several issues in modern medicine. I think it also gives an insight into how Docs think about what they do.

We HAVE been trained to treat. We learn about a disease, how to diagnose it, how to treat it. Wash, rinse and repeat. Graduate. But that is only one part of medicine. As with many things in life, the real art is in knowing when NOT to do anything.

Tsukahara Bokuden was a great Japanese sword master who was challenged to a fight by a drunken youth while on a ferry ride. When asked, the old warrior said that his style was the “No Fight Style”, and when pushed to demonstrate his style he suggested they go to an island to fight, so as not to injure the other passengers. Both men jumped into a boat and rowed over to the island, but when the youth leapt out to fight, Tsukahara rowed the boat back to the ferry, leaving the irate young man on the beach – and in the process saving him from certain death at the hands of the superior swordsman.

Bruce Lee reenacted this scene in his immortal film “Enter the Dragon”. To those mindful enough to appreciate it, this scene was not one of humor, but a deliberate attempt to show that avoidance of conflict is better than beating someone by force.

In medicine the same concept can be applied. “Primum non nocere” – first do no harm – is the idea that a medical intervention may hurt the patient, and we should at the beginning (first) consider whether an intervention may be harmful. We do harm all the time of course, chemotherapy for cancer is the best example where the benefits usually outweigh the cost, but we should always be aware of that premise. In one of my medical exams the marking was such that an incorrect answer cost you marks, whereas doing nothing didn’t affect the score either way. This penalized students who acted without fully knowing what was going on – the same idea.

Of course the decision to not intervene is just that – still a decision – and not always one to be taken lightly. It is different from simply doing nothing. Often the decision to not intervene involves a calculated risk that nothing will go wrong, and one argument for excessive testing and treatment is defensive medicine. Another feature is that patients often expect, either implicitly or explicitly, that something will get done. But that something doesn’t always have to mean a prescription or a lab test. Actually performing a test may do harm – radiation from CT scans may cause future cancer for example, colonoscopy can cause perforation, the discovery of “incidentalomas” (a incidental finding on a scan used to look for something else) can lead to additional testing just to rule out cancer or something else. In addition the psychological impact of an “abnormal” result should not be underestimated. In the US we spend twice as much per capita on healthcare than other Developed countries and yet have worse health outcomes (US Life expectancy is 38th in the world, slightly worse than Cuba). Excessive testing is one part of that overspending.

It may well be that patients ask for tests for some of the same reasons that Docs do – they may not trust their clinical skills of history taking or physical exam. Truth be told, a good H&P will give you the answer (either a diagnosis or reassurance) the vast majority of the time. And if that information is properly communicated to the patient they may well be happy with fewer interventions. A recent study from Israel supports the idea that CT scans are only helpful in a third of cases when they are used, and physicians were accurate without them 80-85% of the time. This supports the notion that clinical skills are impressively accurate even for hidden injuries, and that better guidelines are needed for when to scan people’s heads! One study from a family practice clinic showed that if better communication skills were used, the patients had fewer tests and referrals.

A key point of this is the effort one must put into convincing someone that a test isn’t needed. Even with “obvious” examples, performing a thorough physical examination will not only cement your own thoughts as a medic but will also demonstrate to the patient or parent that you are thorough! Show a little empathy or concern, make sure you explain everything and have a backup plan or safety net for them (eg a followup visit or phone call). When a patient trusts a machine or lab test above their physician there’s a problem…and these are skills and behaviors that can help build trust. Clearly this is a lot different than just “doing nothing”. The English medics have a phrase for this – MICO. Masterly Inactivity and Catlike Observation. It nicely sums up the concept of knowing what you’re doing, non-intervention, and keeping an eye out for changes. (If someone is sick you always have the option of MICOS – Masterly Inactivity, Catlike Observation, and Steroids.)

I do wonder sometimes, as I watch the techs and phlebotomists scurry about the hospital, if the doctors actually had to DO these additional tests themselves would they order them so much? In that setting, investing a few minutes of your time to talk might be preferable to doing the test.

Then there are the drugs and treatments we use – misuse of antibiotics for viral infections, medications to treat the side effects of medications, quantity of life sometimes is considered more valuable than quality of life. Even in the ICU setting, I have often seen kids on the ventilator who just need to be extubated so we can “get out of their way”, and let them breathe on their own. Sometimes an “information prescription”, some good advice, reassurance, is just what the patient is after rather than a pill. The “quick-fix” mentality is the enemy here, and we have to be wary of believing that a magic pill exists to fix a problem that good old fashioned hard work could help far more easily. Direct to consumer advertising doesn’t help…but that’s a rant for another time.

It seems to me that practicing medicine without doing tests all the time, or prescribing treatments all the time, is a perfectly valid way to go. Test when you need to, treat when you need to – but more judicious practice will, in the end, serve us all well. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that when I took my Pediatric board exams I kept feeling as if the questions were pushing me towards non-intervention/reassurance a lot of the time. I guess I was mostly right when I chose those answers since I passed the boards 🙂

The bottom line is that when discussing treatment options with your patient (you DO discuss the options, right?) non-intervention is often an option even if it’s not recommended or the best course of action, it’s still an option. Remember that.

Gardasil hysteria plays into hands of pediatricians

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Antivax, Children, Public Health, Vaccines on August 13, 2011

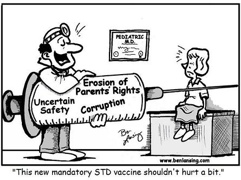

Cartoon by Ben Lansing – from Age of Autism website

Cartoon by Ben Lansing – from Age of Autism website

Stories like this one at anti vaccine sites are unfortunately typical in their misinformation and use of hyperbole and sound bites rather than informing the reader in a non-biased manner. What I found amusing is that the specific approach used in this article actually plays into the hands of pediatricians…

Let’s ignore the rhetoric of the “dangerous” HPV vaccine (it is not) or the claim that it has caused “as many as twelve deaths in the US alone” (it has not) and focus on the headline of the piece.

“California mulls giving 12-year-olds STD vaccine Gardasil without parental consent”

While being technically correct that Gardasil does indeed protect against a sexually transmitted virus, the implications here are clear – anything involving 12 years olds and STDs is immoral, and anything where the parents have no say is unethical. Putting the two together is an order of magnitude worse!

Far from implying that 12 year olds are “sexual animals” (their words, not mine) the simple fact is that the 11-12 year old well-child visit is a perfect time to address many aspects of preventative care before the child becomes a teenager. This is why the vaccine is recommended at 11 years even though it is approved down to 9 years of age. Updating the vaccines at that visit is a no-brainer. With any luck the kids are NOT YET “sexual animals”, because ideally you want to protect them before that happens. Getting the HPV shots started 6 months before a teen’s “big night” is, I’m sure, not something they have on the calendar…and having taken care of my share of teenage mothers I can vouch for the fact that planning their sexual activity is clearly not something they are very good at at all.

Sexual health for teens includes proper counseling, education, and access to contraception. Abstinence is the most obvious way to avoid STDs and unwanted pregnancies, but abstinence-only education is associated with HIGHER rates of pregnancy and SIMILAR rates of STDs than more well-rounded education! Over half of abstinence “pledgers” will still go on to have pre-marital sex, the same rate as teens who don’t pledge abstinence (80% in fact denied ever having pledged in the first place…) While there may be an initial delay in the first sexual episode, after that the lack of proper education really does these people a disservice (if they are delaying sex, but their STD rates are similar, then someone is playing catch-up!) Not giving them a vaccine that, if all three shots are given on time, protects against 70% of cervical cancer is simply wrong.

The second part is whether or not parents have a say. In general, parents operate under the assumption that they are responsible for the health and well-being of their child until they are an adult. They get to call the shots (pardon the pun) and have access to all the information. Sadly, as some discover, that simply isn’t true. Parents do have the responsibility to take care of their kids, but if they fail to do so then the authorities can step in and take over that responsibility – most obviously in cases of child abuse or neglect. Effectively the State acts as if it is responsible for the welfare of children and merely delegates that responsibility to the kids’ parents or legal guardians – a delegation they can revoke if need be. But a lesser known area where parents lose their right to control their kid’s healthcare is sexual health.

It is clear that in order for teens to feel safe about coming forward to ask for help with sexual health issues, this MUST be done under strict confidentiality. Having a requirement that parents provide consent to treat (as is needed for every other situation except life-threatening emergencies) is a barrier to effective safe treatment of teens sexual health issues. The laws vary by State but in many places minors are allowed access to confidential sexual healthcare.

Ironically perhaps, by trying to demonize Gardasil as a way in which the medical establishment is sexualizing the youth of today, and labeling it explicitly as a sexual health vaccine, antivax groups are automatically putting it outside the remit of parental oversight. In the same way as a sexually active teen can (and should) get advice, contraception or treatment for STDs without fear of their parents knowing about it, I see no reason why they shouldn’t be allowed to ask for a sexual health vaccine under the same existing laws.