Posts Tagged healthcare

Powassan virus – an “uptick” in cases, or simply better awareness?

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Nick Bennett MD, Public Health, Uncategorized, viruses on May 9, 2024

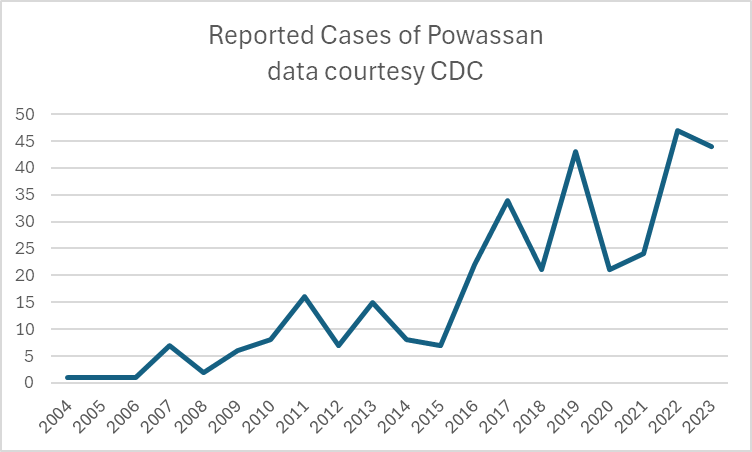

A recent headline caught my eye, discussing an increase in the annual reported cases of Powassan virus – a virus which (for reasons that will become obvious) is near and dear to me. I decided to take a look at the actual data in more detail, and discuss a bit of that here, because understanding viruses like Powassan has implications beyond just this one infection.

Let’s start with what Powassan virus really is – it’s an arbovirus, meaning transmitted by arthropods (in this case, Ixodes ticks), and has an ability to cause a form of encephalitis. It is in fact closely related to the Tick Borne Encephalitis (TBE) virus, but Powassan virus was actually named after the town in Ontario where it was first discovered. It’s highly likely that many (perhaps the majority) of infections don’t go on to cause very serious disease, but the actual risk of encephalitis from it is unknown because the total number of cases isn’t really known. Of the symptomatic cases, about half are quite serious and 10% are fatal. The CDC has made it a nationally reportable infection, but the tricky part is knowing when to even think about it…

I diagnosed the first ever case of Powassan in Connecticut in 2016. It really was a bit of a crazy story, and truly a perfect storm of being in the right place at the right time. A young infant boy was admitted to the ICU with seizures and a very clear story of a few hours of a tick being attached to his leg 2 weeks earlier. The tick was brought into the house on a family member’s clothing, and probably got onto the child during a feed while being held by this person. The medical team had quite correctly ruled out most tick-borne infections due to the very short attachment time, but I knew that there was one exception – at least in animal models, Powassan virus could be transmitted in as few as 15 minutes. So it was possible, but was it probable? The clincher was the MRI report, which had a very distinct pattern showing “restricted diffusion of the basal ganglia and rostral thalami, as well as the left pulvinar”. There was no sign of more widespread of diffuse signal changes as you might see with ADEM (acute disseminated encephalomyelitis) or cerebellar changes as you might see with enterovirus. No hemorrhagic changes, as with herpes simplex. The laterality and location of the damage matched the physical symptoms (motor dysfunction affecting the right more than left), but more importantly it was also similar to previous reported scans from patients with arthropod-borne flaviviruses, including Powassan. Choi and Taylor wrote in a 2012 case report “MRI images of the patient’s central nervous system (CNS) were unique, and when such images are encountered in the clinical setting, Powassan viral infection should be considered.” We were able to test the baby’s spinal fluid at the CDC for Powassan, and it came back positive.

The points to make about this case are several – firstly, the recurring comment from most (probably all) of my colleagues when I made the diagnosis was “What made you think of it?” Honestly, it was mostly the fact that I had training in a state where Powassan was well-known and we would consider it routinely. I simply added it to the differential and saw that not only could I not rule it out, I had some evidence to support it! But the issue here is that there were probably many cases of Powassan over the years that doctors had been seeing, but simply never thought of testing. Powassan was not on a routine viral encephalitis panel in Connecticut (it’s a send-out to the CDC), whereas some other State laboratories like New York test for it automatically on their own encephalitis panel, in addition to sending/reporting to the CDC. It is very much a case of out of sight, out of mind.

Secondly, even if some physicians had considered and tested for the virus somehow, Connecticut didn’t make Powassan a reportable disease until 2019 (more than 2 years after I made the first diagnosis in the state). It’s really hard to measure something if you’re not counting it…and of course even hard to count something if you’re not looking for it!

So this makes it really, really hard to know what to do with news that “Powassan cases are increasing.” Reports are increasing, but so is awareness, and testing availability – it doesn’t mean that actual infections with the virus are going up. It is possible that they are…but the case reports alone aren’t enough to make that conclusion. You really have to understand the reporting infrastructure and testing limitations in the context of a specific disease when trying to interpret the changes you might see in any sort of incidence or prevalence data.

There isn’t a vaccine yet for Powassan virus, although when I last checked research was ongoing (and there is a vaccine for TBE). The best way to prevent infection is to avoid any kind of tick exposure at all – cover skin, use DEET, avoid tramping through the wilderness in areas where the virus is known to be in ticks, and check your pets! Also – change your clothing when you get indoors from activities that might have exposed you to ticks…

Bonus if you’ve made it this far – you can check out my TV appearance on Monsters Inside Me below!

Regional Medical Monitors – does location really matter?

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Uncategorized on April 5, 2024

In my ongoing saga series on clinical research, I thought I’d share my thoughts on the advantages and disadvantages of requiring regional medical monitors be located in specific countries.

One of the points raised during the planning stages of a clinical trial is often the geographic location of the team members. The Clinical team in particular pretty much has to be based locally because they will be performing site visits and interacting very closely with the staff and investigators, but it’s not unusual for other team members to be based around the globe. Data management team members for example are frequently located in Asia due to a large population of skilled talent available at more economic salaries than if they were based in Western Europe or the USA, and the fact that their work can readily be performed remotely and asynchronously with the rest of the project. But what about the Medical team?

The Medical Monitors are typically physicians with at least some experience in clinical practice (although the actual time people have spent varies considerably), and many have some degree of subspecialty training. The interesting thing is that a very large part of the job is subspeciality agnostic – the safety data we review all looks the same, and it’s largely a case of lining up the findings with the study-specific protocol to weed out the more detailed anomalies. Whether the study drug is being given for one thing or another is largely a moot point. When looking at things like protocol design and study planning and execution, there is absolutely an element of subspeciality knowledge required, but it isn’t that unusual for a physician trained in one area to find themselves working on a clinical trial in another. Furthermore, clinical trials are often global in nature and may have sites not just in different time-zones, but on different continents, and the Medical Monitoring work itself is readily performed remotely. For this and other reasons, the physical location of the Medical Monitor may not be considered relevant, but I would argue that there are very good reasons to keep the Medical team regional and optimized for the study, beyond the simple consideration of time-zones.

In the early planning stages, similar to being a subject matter expert from the disease/treatment perspective, it can be critical to have the insight of a local physician when considering things like screening failure rates, ease of enrollment, site and investigator selection, and even country-specific nuances on treatment guidelines or standards of care. For example, if a protocol requires that a specific comparator drug be used, but that drug isn’t approved or recommended in some countries, then it would be a mistake to try to conduct the study in those countries. Certain medical conditions are more or less common around the world, whether due to genetic or environmental factors, and these can dramatically impact enrollment rates and timelines. While it is true that a lot of this information can be obtained and understood by any physician, I think it’s still prudent to consult someone with that knowledge from a medical perspective.

During one large project I was on, we received feedback that a particular medical test was likely under-budgeted, which might lead to sites refusing the take the study on if it were not reimbursed properly. It was something that was highly unusual in routine medical care, but which I happened to have knowledge of and an awareness of the complexity of the procedure. Having an awareness also of the way the American healthcare system tracked and billed for these tests, I was able to direct the budget analysts to the correct amount to cover which impacted not just the proposal I was currently working on, but any others that used the same test. Someone without that knowledge of how the system worked might not have even known that there was an answer out there to find, never mind find it.

One area that is also important, although it’s often not realized until it’s needed, is clear communication with the sites and Investigators. While it’s true that English is widely used and understood, and tends to be the “lingua franca” of the research world, it’s also true that English is a second language for most. It seems prudent, if not simply polite, to be able to converse with site staff and investigators in their native language, and furthermore to have the social cues and etiquette familiar to them. I can speak French fairly well, but I know I cannot communicate the nuances in French that I can in English. At best, this can slow down communication if a third-party is required on a phone call to interpret in real time – at worst, it can lead to miscommunication and inadvertent offense. I have found that the issues are compounded if a person who natively speaks one language converses in English with someone who natively speaks another, and because clarity and attention to detail are SO important, I think it does behoove us to consider this aspect of study execution when assigning Medical Monitors. I don’t think this necessarily requires physicians geographically local to the sites, but doing so definitely decreases the odds of miscommunication.

Having already said that geographic location is irrelevant when considering the basic data and safety review tasks (with the exception of nuances in country/region specific regulatory reporting of urgent cases), there is other reasons for appointing Medical Monitors in alternative locations to the main study sites, especially if the time-zones at least line up. For one, it may be economically advantageous to hire on physicians from certain countries, or the volume of work may simply require multiple people with the team members scattered. There is also the very real possibility that the most experienced or suitable physician for that study isn’t local, or the sponsor may have a specific preference based on past experience with that person, so obviously a number of factors need to be considered.

Importantly, because the needs are different for project development versus execution, It may be the case that the subject-matter expert assigned to the initial proposal team isn’t assigned as the Medical Monitor. In that situation, it’s crucial for a comprehensive hand-off/kick-off meeting to occur to make sure that any issues or risks identified during the initial work are communicated over to the main team.

From the perspective of the sponsor, I would consider all of these issues when looking at the Medical Monitor assigned to your study – what aspects are most important to you, and what tasks are they most likely to be performing? I would say that if site communication and insights are important, then advocating for a local assignment would be a good idea. If you consider that subject-matter or clinical trial design expertise is more important, then you may want to be targeted in your selection regardless of geographic location. I am also a huge advocate for remote working for Medical Monitors, especially when considering all the factors above: there is a finite pool of experienced experts and if you happen to find someone with the right mix of clinical and research time, covering the right subject-matter, and with the personality and work-ethic to excel in clinical research, you absolutely should not limit your recruitment to physicians who are willing to relocate. Most physicians who are at the stage in their careers where a move to industry is feasible are in their middle years, settled with children and houses, and in many cases burned out with the time and demands of clinical care. Being told they have to uproot their family and commute through traffic to a desk job in an office is not appealing at all. I have seen several companies, both in the CRO world and in big Pharma (less so in Biotech interestingly enough), require their Medical Monitors to relocate and work on-site. I simply do not think there is a need for that in this line of work, especially in the post-pandemic era where work-from-home infrastructure is so well developed. If you’re requiring your talent to relocate you’re effectively giving the talent away to your competitors…

What’s been your experiences working as, or with, a regional medical monitor? I’d love to hear about the advantages and challenges you’ve experienced.

Everything You Wanted to Know About Protocol Deviations, but Were Afraid to Ask

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Clinical Trials, Research on March 28, 2024

In my first post on Clinical Research, I mentioned how important it was for Investigators to adhere to the protocol, but I didn’t really go into detail on the whys and wherefores. Protocol Deviations (PDs) are often misunderstood, even by those who are tasked with identifying and categorizing them, so I wanted to write this breakdown of the concept and why it matters to everybody involved in clinical research.

By definition, a PD is anything that causes one or more subjects to deviate from the strictly defined procedures and events laid out in the protocol. You might imagine then that it wouldn’t be difficult for this to happen – for example, if a subject gets sick and cannot attend a study visit when they’re supposed to, that would be a PD. That wouldn’t be anybody’s fault, it’s simply something that couldn’t be avoided, but it is still a PD. More seriously if a pharmacy fridge fails without anyone noticing, and a subject is given a medication that might be ineffective, that would also be a PD.

There used to be a term of Protocol Violations (which were deemed more serious) and PDs, but that guidance has since been clarified/rescinded and now all should simply be reported as PDs, and further categorized into Important or Not Important. Important PDs are those that would impact the rights, welfare, or safety of subjects, or would potentially negatively impact the integrity of the data. Non-Important PDs are divergences from the protocol that do not significantly impact subject safety or data integrity. In part, I think this was to reduce the perception that PDs were a punitive act against the sites and Investigators. Investigators often feel that they are being blamed for events that are outside of their control (for example, sick subjects not showing up), or equipment that doesn’t work. There is a fear, which is in part founded on the reality that they are wholly responsible for the research conducted, that too many PDs will lead to their ability and integrity being called into question. It is true that in the very worst cases an IRB can revoke an Investigator’s ability to conduct scientific research, but in more than 99.99% of instances I would say that the PDs are meant as an administrative and a statistical tool, and certainly are never intended as punitive.

The true purposes of detecting PDs fall into two broad categories – regulatory, and operational. From a regulatory perspective, it is absolutely crucial to detect and identify a “per protocol population” – the group of subjects who, as best as reasonably possible, followed the protocol as agreed to by the regulatory body (e.g. the FDA in the USA). Without this, the sponsor for the study cannot possibly go back to the FDA and say “Look, we proved our drug is safe and effective – please approve it for us!”. If too few subjects followed the protocol, as agreed, then the FDA will simply refuse and tell the sponsor to go back and get more subjects. This is why it is so crucial that Investigators do not willingly deviate from the protocol, even if (and I cannot stress this enough) they would do something different under the normal standards of medical care. Losing one subject here and there is not too great a problem, but losing hundreds (or even thousands) of subjects due to PDs can be devastating to a clinical trial. For this reason some studies retain the “violation” distinction for the most serious PDs that would drop a subject from the per-protocol population, whereas others might opt for a designation of Major or Minor PDs. The distinctions are crucial, and must be clearly defined by the entire project team, including the Clinical Operations, Medical Monitoring, Data Management and Statistical team members. Many of the PDs will be detected by Clin Ops during their site visits or through remote data monitoring; a large chunk are detected during Medical data review (for example the use of prohibited medications, or potential exclusion criteria in medical history); and without the input of a statistician and data manager it isn’t possible to properly assess the impact of these PDs on the final analysis of the clinical trial. In some cases, sites may be asked to track additional information, or the data management team may have to code custom programming to identify and track certain PDs. In one study I was on, the out-of-window visits were subdivided into Major or not depending on how far out of window they were, and only for certain key study endpoints. This is the kind of nuance that can’t be simply tracked as an “out of window” visit – it needs to be “out of window for Visit X by Y days”, and would absolutely need custom programming (and very clearly written protocol deviation guidance) to detect, if the sponsor wanted to go down that route.

I was involved in a company-wide initiative to update and improve our Protocol Deviation process, to optimize the process and understanding of each team member on their role. Medical Monitors in particular have to weigh in on Important PDs, which are defined as any that might impact subject safety or data integrity – ultimately we have to decide if that subject should be dropped from the study or if they may continue. Sponsors often don’t appreciate the distinctions between the different levels of PD, and the work they entail, so it’s important to communicate that clearly during study start-up. PDs are also very much study-specific – for example an “expedited PD” may require the Medical Monitor to contact the site and intervene on an urgent basis, but it makes no sense to mark certain PDs as expedited in a single-dose study (such as a vaccine study) when the PD would be detected long after the subject was dosed. It also makes no sense to mark PDs that would be detected by the Medical Monitor as “expedited”, because they already know about them! If a missed study visit occurs then it’s reasonable to track that as a single PD, and not necessary to track separate PDs for every missing procedure during that visit (yes, I’ve seen this done inadvertently!) The goal of this process improvement was to streamline and align the PD process between all the relevant team members, and ultimate save time and money throughout the entire study timeline.

The second reason for detecting PDs is operationally – the Clin Ops team monitors and tracks PDs, and especially important is the categorizing of PDs. For example, if they find that there are many PDs for inclusion/exclusion criteria, it might be that the protocol is unclear and needs revision. If they find that one site has many PDs compared to their peers it might signal an issue that requires site staff retraining – and the flip side of course is that if a site has very few or no PDs that they aren’t being truthful in their data reporting… Ideally these are reporting back to the Sponsors regularly throughout the study, although I have come across some smaller biotech companies who have asked merely for updates perhaps one time during the study, and once at the end. In my opinion this is a recipe for disaster – it means that the operational benefits of the PDs are diluted, if not lost, and it also means that potential revisions to the protocol that could improve the quality of the data (or subject safety) are not made. The very best companies use PDs as “constructive criticism” to optimize their study sites and protocol. PDs can also be an absolute bear to properly collect and categorize, and the worst thing that could happen to a study team is to discover right at the very end of a study that there are hundreds (or thousands) of PDs to address when there are looming deadlines of database locks.

There are two further things I want to highlight about PDs. There is a hierarchy that actually stretches very high up – PDs can be at the study level, the country level, the site level, or the subject level. Study and country-level PDs are extremely rare. Site level PDs do occur, but they are often misidentified, and that can cause a lot of work. By definition, a site-level PD affects all subjects at that site. This is a statistical definition, not a common-sense definition. For example, a broken pharmacy fridge might be incorrectly identified and recorded as a single site level PD (failure to adequately maintain and monitor study equipment) – but the problem then arises in the final analysis, where EVERY subject from that site would be tagged with that PD! In truth, the clinical monitor who visits the site has to correctly identify the subject(s) impacted by the event, which usually means tracking specific dates, subject timelines, and drug deliveries to figure it all out. They would have to identify and report PDs on the affected subjects, and ONLY the affected subjects. This might mean reporting 23 separate PDs (one for each of 23 affected subjects) instead of one site level PD, unless the site has only enrolled 23 subjects! But trust me I say this is the correct way to do it – this is exactly how the FDA will ask the events to be captured if they were to visit the site for an audit. I perhaps misspoke above when I said that the worst thing that can happen is for a last minute deluge of PDs just prior to database lock – imagine a deluge of PDs after database lock because of an FDA audit findings…

And finally, the reason for the meme I made above (which I have actually presented in Investigator training slides…). Sites often ask for “exemptions” or “permission” for a PD ahead of time, for example if they know that a particular subject is going to be out of town and miss a study visit, or if a subject has a prohibited medical condition but would otherwise qualify for inclusion in the study. The thought is, if they ask ahead of time they won’t be “dinged” with a PD.

It is a very, very, very bad idea to grant exemptions to PDs. As I said above, PDs are there to ensure data integrity and that the per-protocol population is sufficient to be submitted for regulatory approval. If a significant PD is granted ahead of time, the entire clinical trial is put at risk. I was trained to never, ever, grant a PD exemption. We can acknowledge that a deviation has (or will) occur, but it will be reported, and it will be categorized, and if need be the local IRB will also have to hear about it. Now, there are some sponsors that will grant PD exemptions on a case-by-case basis but that is their risk to bear. Not every event reported as a PD is actually a deviation when fully reviewed, and it isn’t unreasonable to void a PD that shouldn’t be there, but they would have to defend that decision should a regulatory authority question it, and if you don’t think that a regulatory authority will detect discrepancies in individual protocol deviations and subject data, then you haven’t witnessed a regulatory audit… What the site/Investigator really needs to ask is “Can this subject continue in the study, should this PD occur?” That’s an entirely different question, and is probably what the site is really wanting to know, but even if the answer is “yes” then every effort needs to be made to follow the protocol – the Investigator literally signed a legal document saying they would do this (I talked about Investigator responsibilities last week…)

To summarize – PDs are inevitable, even if they should be avoided as much as possible, and they are very important tools used during the conduct and in the final analysis of a clinical trial. Clear PD guidance should be established very early on in the study start-up to identify areas of risk and mitigation steps, and PDs should be routinely reviewed with the sponsor so that course corrections or staff retraining can be done as needed. Proper categorizing and coding of PDs (Important, Non-Important, Major, Minor, Expedited…) will dramatically improve the quality of the data and project workflow for everybody involved. Sites should not fear PDs, and they absolutely should not attempt to cover them up, but please don’t ask for exemptions.

Drop me a line, or follow this blog, if you want to learn more about PDs and how best to avoid or manage them.

MRSA’s everywhere – ignore the MRSA

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Bacteria, Infections, Public Health on November 16, 2012

Ermahgerd! It’s MIRZAH!

MRSA, affectionately pronounced “mur-sah”, and the abbreviation for “methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus”, has become the epidemic of our time.

Everyone thinks they know what it is. Few actually have a good handle on what it really means, especially with kids.

MRSA was first described back in good old Blighty in the 1960’s, not long after the drug methicillin was released in an attempt to combat the rise in penicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus. In the modern era methicillin is no longer available, due to kidney toxicities that are much less in the current selection of anti-staph penicillins (nafcillin and oxacillin), but the MRSA tag remains in use.

In practical, and literal terms, it simply means that the organism in question is resistant to that particular antibiotic. Well, whoopdedoo. Lets just pick another. Except you can’t. The way in which staph becomes resistant to methicillin is through the production of an altered protein that renders the bug resistant to EVERY antibiotic in that entire FAMILY of antibiotics. Penicillin? Gone. Cephalosporins? Gone. Beta-lactamase inhibitors? Useless. Carbapenems? Fat chance.

So you go to another class – quinolones, aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, sulfonamides – but none of them are especially active against staph and…wait for it….MRSA is often resistant to these drugs too.

The first place in which MRSA was discovered was in healthcare settings – long-term care facilities and hospitals. The overuse and abuse of antibiotics selected for strains of bacteria that had acquired all sorts of resistance genes. In fact, the gene for hospital-acquired MRSA is a multi-segment behemoth that carries with it all sorts of additional genes, so the whole lot are inherited together. MRSA infections were associated with severe, invasive disease and death, usually in adults already weakened by other diseases. Due to delays in starting the right treatment, and being forced to use second-line, less effective drugs like vancomycin, MRSA infections add to hospital stays and healthcare costs. Like to the tune of $60,000 apiece.

Just as the world was getting used to dealing with MRSA in hospitals, we started hearing about it in the community. People were showing up with skin abscesses, boils and other infections that were, in about half of cases, growing out MRSA. Worse, they didn’t seem to have any link to the typical risk factors of diabetes, renal failure, cancer, prolonged hospital stay etc. And even more scarily, this was being seen in kids.

But they’re different from the old hospital-acquired MRSA cases. The community MRSA gene cassette is far smaller, lacking the resistance genes of the hospital MRSA. We have a small, but reliable list of antibiotics to use to treat it. Invasive disease is unusual, skin infections are the norm. I have not, yet, seen a real hospital-acquired strain of MRSA in a child. I have seen a few kids pick up MRSA while in the hospital, but it’s always been the “community” strain brought in by visitors, family or other patients.

Diagram of MRSA gene cassettes – hospital (top, types I thru III) versus community (bottom, types IV thru VI)

Right now, I see a steady stream of kids with MRSA in my clinic and in the hospital. By far the vast majority are recurrent skin infections, often bouncing around various family members. Parents, reading up on MRSA online are understandably freaked out. Friends and relatives shun their kids, for fear of picking it up. Furnishings and furniture are steam-cleaned and thrown out, course after course of an antibiotic is given to treat each infection, but they never seem to go away. Even pets end up getting “swabbed” and tested in the lab, and yes, some are sent on their way as the presumed culprit.

None of this matters.

The truth of the matter is, while MRSA does indeed cause a good chunk of these kind of infections, it’s not got the hold on it. Just as many regular, sensitive staph (MSSA) cause these things. Fully one third of the population carries staph aureus on them – and clearly one third of the population is not suffering from recurrent skin infections. Carrying staph doesn’t mean you’ll get infections. And, annoyingly, you can test negative for staph from a swab (typically done from the nose) and still have infections elsewhere, such as the armpit, legs, or buttocks. We’re exposed to staph everywhere, all the time – and we mostly don’t even know it. That’s if we don’t have it already.

The reason why the skin infections keep happening is due to an entirely separate set of genes, related to immune evasion and skin invasion, which although more common in MRSA are also in some MSSA. (They are, interestingly, mostly absent in the hospital MRSA strains.) The way to get rid of it, if the levels are high enough for these infections to keep happening, is simply to decolonize the skin. That can be done with chlorhexidine washes and bactroban nasal ointment (a two week protocol), but you also have to prevent re-colonization, a more difficult proposition. Bathroom surfaces need to be bleached, towels washed daily (paper towels for hand washing) and EVERYONE in the household needs to have this done. There’s no point focusing on little Johnny with his butt abscesses if mommy and daddy, who are carriers, give him a hug and spread it back.

I never promise that with this approach staph will go away entirely. What we do know is that, if everything is done at once, you CAN eradicate staph at least temporarily from the skin. What we also know is that a third of the population carries staph….so wait long enough and you’ll get it again. I hope to merely reduce the frequency of outbreaks.

In my experience…this seems to work. Except in situations where kids have severe eczema or other skin issues, or where they’re not following EVERY step of the plan, I generally don’t see these kids back again.

So that’s prevention – what about cure? How should we treat these kinds of infections when they do show up? One drug that has seen a resurgence of late is bactrim – trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. A combination drug that is designed to inhibit the bacteria’s use of a chemical called folate which is a key component of DNA creation. It sounds good on paper, stop the bacteria from growing and it’ll die. In the lab, staph is often 99% sensitive or more (good odds when your risk of resistance to other staph drugs is around 50%!). The trouble is, in an abscess there is pus. And pus is basically dead and dying cells and bacteria. That’s a lot of DNA hanging around. Using bactrim in that setting is a lot like telling a farmer he can’t grow any more food, but putting him in a grocery store. He ain’t gonna starve any time soon. Bactrim also ignores the risk of strep, which are the other cause of skin infections and which are inherently resistant to bactrim. As such, deliberately targeting MRSA with this kind of approach actually results in MORE treatment failures than using a simple staph drug like cephalexin, even though that shouldn’t work with MRSA! You WILL get treatment failures with cephalexin too of course, and some with the other drugs like clindamycin, doxycycline etc. But it’s as if one should ignore the MRSA when planning your treatment. Drain abscesses (you usually don’t even need antibiotics if you do that) and then use a regular “skin infection” drug to minimize side effects and maximize your chances of success. These days we have NO ideal drug for empiric therapy of skin infections – but we certainly do worse if we panic about MRSA and try to tackle that first. Weird.

Of course sick patients are a different matter – even though the risk of severe invasive disease is low, the consequences are dire. You should ALWAYS cover a very sick patient with vancomycin or other MRSA drug until you know what you’re dealing with.

So I don’t panic about MRSA. I see it all the time. It’s annoying. It’s rarely dangerous. I know that if you focus on it to the detriment of the regular staph and strep you do worse. If someone is a carrier or has an active infection, good hand washing and covering any draining sites is enough to keep it at bay. No need to decontaminate entire schools just because a kid has been found to have MRSA. No need to put everyone on vancomycin if they’re not sick. And if they ARE sick, please don’t use vancomycin by itself, cos its a crappy drug and we only use it because we have to. Don’t bother swabbing just to check for carriage – positive results aren’t worth acting on unless the patient is sick (or, perhaps, due for surgery soon…that’s a whole other issue), and negative results are useless if the patient is actively infected. Deal with the infections, attempt decolonization, move on. Repeat if necessary.

MRSA – it’s a pain in the butt. And not just for the patients.

How safe vaccines led to the resurgence of pertussis

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Antivax, Children, Public Health, Vaccines on August 21, 2012

For those who haven’t been under a rock recently, several parts of the US have seen a surge in pertussis cases. Much of this has been (fairly) blamed on anti-vaccination efforts to reduce herd immunity and the cocooning of vulnerable infants. But that’s not the whole story.

Interestingly enough, it’s now clear that the DTaP vaccine (diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis) doesn’t provide long-lasting immunity. We had some clues with this as an awareness grew of pertussis in older teens and adults, fueled in part by vastly improved testing for pertussis (PCR versus ‘cough plates’ for culture) and a recognition that pertussis in older kids and adults didn’t look like the classic ‘whopping cough’ that youngsters got.

A booster dose of pertussis vaccine was recommended, included as part of the tetanus booster (the new Tdap vaccines). Recent outbreaks seemed to focus on the group of kids aged 10-11 years of age – when vaccine immunity was waning, but just before their Tdap booster – but the recent outbreak in Washington State has involved even 13-14 year olds, who did get their booster!

The question then should be – why does the NEW vaccine work LESS well? The answer is because it is SAFER.

The old DTP vaccine began to get a bad reputation for neurologic disease – in fact a contraindication still exists to withhold pertussis-containing vaccines in kids who develop neurologic issues after pertussis vaccination, even though the vaccine is different. The old DTP contain literally thousands of antigens, based as it was on a relatively impure cocktail of cell culture fragments that contained the pertussis bacteria. It caused a fair amount of immune reaction, and clearly was linked to febrile seizures.

Several high-profile cases of apparently neurologically damaged children (leading to the formation of some of the early modern anti-vaccine movement) pushed the vaccine manufacturers to create a cleaner vaccine, an ‘acellular’ pertussis vaccine, which is why we have DTP and DTaP. DTaP doesn’t have the same link of febrile seizures and no link to any neurologic issues (interestingly, as detailed in Paul Offit’s book on the history of antivaccine junk science, neither do any of the original DTP kids…it was all a big screwup). Tdap is even less immunogenic as it has slower concentration of antigens – you can tell this because it has a small “p” instead of a big “P”. True story.

The trouble of course is that by having a less inflammatory response, with far fewer antigens, the protection is less. The original DTP vaccine contained more antigens than the ENTIRE modern vaccine schedule does, several times over. Any statement about ‘too many too soon’ is pure bunk – our kids are exposed to fewer vaccine antigens in their entire schedule that we were in one vaccine.

This story highlights several points – firstly, contrary to antivax propaganda, not only are there mechanisms in place to detect and respond to potential vaccine side effects but there are CHANGES made to the vaccines in an attempt to keep people safe. (Probably the only positive thing to come out of the antivax movement is the establishment of the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, VAERS). Secondly, there are compromises to be made – more effective sometimes also means more side effects, so if you want to lower one you may end up lowering the other.

There is also data from Europe that as the vaccine strains of pertussis wane, there is strain replacement with potentially more virulent strains. So although we are seeing fewer cases, those cases we do see may be more serious (this finding hasn’t yet held true for the US…as far as I know).

Of course the antivax brigade have twisted the story yet again “Whooping Cough Epidemic Caused by Virulent New Pertussis Strain—And It’s the Result of Vaccine” shouted one headline. While technically true it doesn’t really go into the real explanation of WHY…even more impressive, but entirely unsurprisingly to me, the actual article the antivax site uses to support their claim starts with the words “Before childhood vaccination was introduced in the 1940s, pertussis was a major cause of infant death world- wide. Widespread vaccination of children succeeded in reducing illness and death.” which not only proves how disingenuous antivax proponents are, but how stupid they are. The first rule of selective quotation is to use sources that support your argument.

Sadly, those who believe antivax propaganda are not usually stupid – if anything they tend to be more educated than average, and well read. They just read the wrong things. Not everyone can go to medical school after all.

Then again, even that isn’t foolproof. One of the original antivax “Expert” witnesses from the UK trials that showed the DTP link with neurologic illness to be wrong went on to further his infamy with AIDS denialism.

Much of the details on the stories of the DTP and DTaP history are in Paul Offit’s book – Deadly Choices, which I highly recommend. In it he not only details how antivax proponents twist science and the facts to suit their case, but also how they nearly brought down the entire US vaccine industry through irresponsible and indefensible litigation. The vaccine WORKS to reduce serious illness from pertussis and undoubtedly saves lives. It’s not perfect, no one has ever said a vaccine was perfect – at least, not unless they were trying to make a point that it wasn’t…

Counterintuition – why neonatal herpes turns logic on its head

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Children, Guidelines, Infections on August 9, 2012

“No maternal history of herpes”

When dealing with a newborn baby with a fever, those are words that strike fear into my heart.

Wait, what? You said no maternal history? Yep, that’s right.

Neonatal herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a topic that is full of counterintuitive statements, and far too much confusion. The wrong people get tested, the wrong people get treated, the wrong babies get worked up aggressively. When other docs diligently rattle off the “pertinent” aspects of the maternal history and clinical examination of the baby, in my mind I’m mostly saying “Don’t care, don’t care, don’t care….” before I interject and ask about test results that often haven’t been ordered.

Based purely on a numbers game, thanks to things like vaccination and Group B Strep prophylaxis, many early onset infections in newborns have been reduced. There is simply less infectious disease hanging around. But as a result, viral infections like neonatal herpes are proportionately becoming larger players – in some hospitals it is as common as bacterial meningitis. And neonatal HSV is a killer.

HSV comes in three distinct flavors – the least lethal is skin-eye-mucus membrane (SEM) disease. This is how many people expect to see herpes – a rash, typically vesicular (clear fluid-filled little blebs) and maybe some eye discharge or mouth sores. Most pediatricians, if they see something like this, appropriately freak out a little bit. SEM disease by itself isn’t too dangerous, and if treated properly is almost never fatal. Herpes is tricky though – in babies it can mimic other rashes, so you really do need a low threshold to consider it. ANY neonatal rash that doesn’t fit a normal neonatal rash (so know your neonatal rashes!) deserves a workup. There is nothing more sobering than to run a case of a neonatal rash by an ID doc and to have them tell you with complete sincerity that “You can save this baby’s life. Get them to an ER. Now.” Untreated SEM disease can progress to infection of the brain.

The most obvious presentation is disseminated disease – which weirdly enough can occur before SEM disease…first week of life or so. The kids are sick – really sick. They can be in shock, bleeding, in liver failure and struggling to breath as the virus overwhelms pretty much every organ system. The problem here is that even faced with this situation bacterial infection is considered immediately, and herpes can still be overlooked or thrown into the mix as an afterthought. Again, good neonatologists and pediatricians will be all over this from the start, having experienced their share of disasters in the past. Disseminated herpes is mostly fatal without treatment – and even with therapy about a third will still die, many of the survivors left with significant disabilities.

The last type of herpes infection is of the brain. Typically presenting later in the neonatal period (3-4 weeks of age, rarely later) herpes encephalitis of the newborn is devastating. Herpes causes a hemorrhagic encephalitis, meaning that it chews your neurons up into a bloody pulp. To a brain that has barely begun its developmental process, this is a disaster. Even if the baby survives they may be blind, deaf, paralyzed or have significant developmental delays.

From how I describe it above you might assume it would be easy to spot these kids. Well, it is – once it’s too late. The success of treating HSV depends to a large extent on how quickly you can start acyclovir – one of the few medicines we have that can treat viral infections (it’s pretty much only used for HSV). Acyclovir can shut down virus replication, but does nothing for those cells already infected. The difficulty with HSV lies in the nuances of the medical history.

Let’s try some armchair science for a bit. Would you, as a baby, rather get HSV from a mother who is having a recurrent outbreak of HSV, with low-levels of virus, and have her give you antibody protection through the placenta…or would you prefer to catch HSV from a mother who is having her FIRST outbreak (which may be without symptoms) with high-levels of virus and no antibody protection? Well, you may ask, how likely is that? The answer is Very. About 90% of all neonatal HSV cases come from mothers with no history of HSV. If your mom DOES have HSV and has a recurrent outbreak, the risk of transmission is about 5%. For a new case – its closer to 50%. Maternal history of HSV is relatively PROTECTIVE for the baby.

But the focus is on the mothers who test positive for HSV during pregnancy. They get put on valtrex (an oral version of acyclovir which is well absorbed), when it has not been shown to sufficiently reduce transmission. They may get a C-section, when that hasn’t been shown to help either (except maybe in the case of active lesions at the time of delivery…and even then it’s unreliable). The mothers who are HSV-negative are ignored, when they are those at highest risk of passing HSV to their babies. In an ideal world, their sexual partners should be tested and if THEY are positive THEY should be put on valtrex to reduce outbreaks and educated about the risks. But the fathers aren’t the patient….so nobody does that.

A big myth about HSV is that all babies with it look sick. Well, they do eventually – but to start with they look pretty normal. I have heard docs say that a baby looked “too good to tap” – meaning they didn’t perform a spinal tap to check for meningitis or HSV encephalitis. Or they don’t test sufficiently for HSV, or don’t start treatment with acyclovir while test results come back (these same babies are almost universally started on antibiotics for presumed bacterial infection). Published case series of proven HSV cases shown over and over again that babies with HSV present with relatively innocuous symptoms. “poor feeding” “fever” “sleepiness” before the more obvious symptoms of “shock” “seizure” or “respiratory distress”. Remember, by the time the baby is sick from HSV the damage has already been done, and you can only try to stop it from getting worse and hope the kid recovers. With bacterial infections we can kill them directly with antibiotics and the damage is usually secondary to the infection, and not because the bacteria are literally eating up your cells and blowing them apart as HSV does. Even with successful treatment, symptomatic HSV in babies has a slow recovery.

So how do you deal with this uncertainty? You can’t trust the mothers history, you can’t trust the baby’s physical examination or symptoms…what do you do?

My approach is to have a low threshold for suspecting HSV in neonates. ANY baby getting worked up for a possible bacterial infection needs to have a workup and empiric treatment for HSV as well. Babies with weird symptoms (especially rashes or neurologic symptoms) need to have HSV considered FIRST, before bacterial causes. HSV is not only potentially devastating – its treatable, and therefore the bad outcomes are preventable.

Fortunately the Committee of Infectious Diseases of the American Academy of Pediatrics has published recommendations – albeit in a rather inaccessible set of paragraphs. I can summarize them here though:

Spinal tap for HSV PCR of spinal fluid.

Liver enzyme testing for disseminated disease – chest x ray if respiratory symptoms.

Surface cultures from eye, mouth, rectum and any skin lesions.Start acyclovir – do not stop until all tests are negative.

Do ALL of this this for EVERY BABY with suspected HSV.

Repeat spinal tap on kids with positive CSF to ensure clearance after 21 days – continue therapy if still positive.

A big mistake I see people making is in testing the spinal fluid to “rule out HSV” but do not doing the rest of the workup. Spinal fluid testing for HSV no more rules out SEM or disseminated disease than a urine culture can diagnose meningitis. I have seen cases missed (or nearly missed) because someone didn’t do the whole thing. You NEED the liver enzyme testing to rule out disseminated disease, and it matters. Treatment for simple SEM is 14 days – treatment for disseminated or CSF disease is 21 days. I have seen a handful of kids with positive CSF tests but with totally normal looking spinal fluid (eg no white cells, normal protein levels etc).

The trouble is HSV, as bad as it is, isn’t all that common among the hundreds of kids you will see with suspected neonatal infection. And many of THEM will be obviously HSV. So many kids get a semi-workup and we get away with it because “whoops, the CSF is positive!” and you treat for 21 days even though you didn’t check the liver enzymes.

But I’ve also seen the opposite – kids who were partially worked up and the diagnosis was missed, or delayed, or the severity was under-appreciated. All too often the “standard of care” let’s these kids slip through the cracks – which is inexcusable in my mind when there are experts who put it down in writing exactly how to work up these cases.

So let’s raise the standard.

Totally useless history:

Mom has no history of HSV

Mom got Valtrex

Mom got a C-section

Baby looks well

REAL risk factors for neonatal HSV:

Prolonged rupture of membranes

Active lesions at time of delivery

NO maternal history of HSV

Prematurity

Age less than 21 days

Unusual rash

Seizures or lethargy

“Sepsis” not responding to antibiotics (oops! too late! – better call your lawyer…)

Testing

CSF PCR

PCR/Culture of skin lesions, eyes, mouth, rectum

Liver enzyme testing

Chest X ray (if symptomatic)

Treatment

Acyclovir 20mg/kg/dose IV every 8 hours

Until all tests are negative (typically 2-3 days empirically)

14 days for proven SEM disease

21 days for disseminated or CNS disease

And if you’re not sure…get a consult…

Consult or curbside?

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in EBM on June 21, 2012

As a consultant my expertise is sought out in largely two ways – a formal consultation (a request to see a patient, obtain a history and perform a physical examination, review laboratory tests and recommend further evaluation or treatment), or a curbside question (a quick hypothetical or general question with the expectation of a simple answer).

An example of a curbside question might be “How many pneumococcal serotype responses would you expect to be normal in an immune evaluation..?”. The answer is 5-10 depending on the age and immunization status of the child, but in reality the correct response is “why the heck are you ordering an immune evaluation on a kid that I know nothing about…?”. The indications for performing an immune evaluation (frequent or unusual infections) are generally the sort of thing an Infectious Disease specialist should have been consulted on!

People often start a curbside question with “This isn’t a consult, but…” as if a consult is a bad thing. It isn’t. A consultation isn’t an inconvenience, it’s what I get paid to do (salaried or not, divisional revenues ARE based on the consults I get called to see). It’s what I ENJOY doing – if it wasn’t I wouldn’t be in the job in the first place. And even if I AM busy, tied up in clinic, or off-site taking call from home, it’s in the patient’s best interest.

No matter how well you quiz someone over the phone, there is no way they can adequately convey the entire medical history and physical exam, the concerns of the patient and family, trends in lab values, recent antibiotics and other meds, and the simple gut vibe of a case… A complete consult, done properly, can take up to an hour and may involve field trips to radiology and the micro lab to check things out for yourself. That is a considerable chunk of time (certainly more than a curbside question) but the value of having a subspecialist see the whole picture cannot be overstated.

The dangers of answering a curbside about a specific patient are legion – you may miss drug allergies or interactions, co-existing diseases or subtle clues in the history or exam that would point towards a specific diagnosis, you will tend to overtreat “just in case”, lacking the reassurance of seeing the patient for yourself, but may just as easily undertreat an infection that had been missed or misdiagnosed. Worse, for the consultant, chances are good that their name will end up in the chart “case discussed with ID”, which medico-legally puts us in a bit of a spot. Then the onus is on you to show that you had no medical obligation or responsibility to the patient should something bad happen…a hassle and horrific waste of time at best.

The other issue is “added value”. Even when I’m called to answer a specific question, I almost always end up offering something else. If I’m asked about best treatment options, I will offer alternative diagnoses. If the question is what this disease could be, I will recommend empiric therapy as well. Every consult is a teaching opportunity, whether about a specific disease or a general bit of advice on ID. For THAT patient I want the docs who consult me to know as much about the disease as I do.

That’s all in theory – what about the evidence? One study of mandatory ID consultation for outpatient IV antibiotic therapy found that 39 of 44 patients had a change of therapy (!), meaning that 88% of the time the current plan was not ideal. 39% of the patients were sent home on oral instead of IV antibiotics, 13 patients (30%) changed medications, 5 patients changed dose, 3 changed planned duration, and 1 patient was stopped entirely. Cost savings were $500 per patient EVEN TAKING INTO ACCOUNT THE CONSULT FEE. In Germany and the US, ID consults have been linked to significantly reduced mortality from staph infections. In Italy, formal ID consultation on ICU patients reduced cost, mortality, ICU stay, length of mechanical ventilation – all due to improvements in antibiotic usage. A financial analysis of curbside consultations suggested that close to $94,000 in revenues were lost in a year by giving advice over the phone without performing (and billing for) an appropriate level of consult. With antibiotic cost savings and increased revenues to the hospital, consults really are a win/win situation.

So what’s really happening when you say “This isn’t a consult, but…”? You’re putting your patient at risk of being treated for the wrong diagnosis, or being wrongly treated for the right diagnosis, you’re increasing hospital costs and increasing patient mortality, and you’re passing up the opportunity to learn something yourself. It’s not good medicine – it’s not good for anyone.

Say it after me: “I’ve got a consult for you…”

This post may or may not have been inspired by the fact that I have had an inordinate number of consults this week which started out as curbsides that would have led to inappropriate care….