Posts Tagged investigators

21 CFR 312.60 General responsibilities of investigators (and more)

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Clinical Trials, Guidelines, Research on March 21, 2024

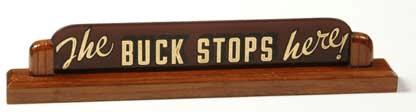

I chose this rather banal title firstly because it is descriptive, but secondly it draws attention to the seriousness of what it means to be an Investigator on a clinical trial. Following up from my first post on this topic, here I’m going to go into more detail on the role and responsibilities.

21 CFR 312.60 – An investigator is responsible for ensuring that an investigation is conducted according to the signed investigator statement, the investigational plan, and applicable regulations; for protecting the rights, safety, and welfare of subjects under the investigator’s care; and for the control of drugs under investigation. An investigator shall obtain the informed consent of each human subject to whom the drug is administered, in accordance with part 50 of this chapter. Additional specific responsibilities of clinical investigators are set forth in this part and in parts 50 and 56 of this chapter.

My first experiences as an Investigator actually stretch back to my earliest days in clinical research in 2004. I was in a kind of twilight zone for a little while, technically hired on as a study coordinator but, with my medical and PhD degrees, I was actually named and delegated responsibilities as a Sub-Investigator on several clinical trials. The training that we all have to do to undertake human subject research makes it very clear how serious and important the role of the Principal Investigator is. The preamble statement from the USA Federal law must be fully comprehended. “An Investigator is responsible for…” Do you really know what that means? If a study coordinator accesses medical records improperly for subject screening, the Investigator is responsible. If a nurse draws the wrong number of blood tests for a specific study visit, the Investigator is responsible. If a pharmacist dispenses the wrong dose of study drug for a subject, the Investigator is responsible. Investigators can (in fact, they must) delegate tasks to study site personnel who are properly trained and qualified to perform those tasks, but delegation does not absolve them of responsibility. This is a significant increase even from the supervisory role that many physicians are in, whether it’s teaching residents or fellows, or supervising Nurse Practitioners or Physician Assistants. As a Principal Investigator the Physician is held responsible even for tasks that they themselves might be incapable of doing (for example, study drug dispensing, or certain types of clinical testing).

This requires a seriousness of mind when a physician decides to undertake clinical research, and in addition it requires considerable support. Whenever I am asked about whether a physician should become an Investigator, my very first thought is “do they have enough support staff?” Having been a study coordinator, and having worked with study coordinators of my own, I have to say that regardless of how good a researcher might think they are, they will absolutely fail in running a clinical trial unless they have a good (if not great) study team. The administrative tasks associated with study start-up alone are Herculean – reviewing the Clinical Trial Agreement, Protocol, and Investigator’s Brochure, adapting the informed consent form (and in some cases, the protocol itself!) to local standards for IRB submission, completing the IRB submission (and any other review boards required), negotiating a budget, organizing sub-Investigators and collaborators, and ensuring adequate space and equipment exists to see subjects, perform procedures, and collect all the required specimens. All of that is before you even see a single subject. If you are able to get all that done, then a representative or two from the sponsor or contract research organization will visit to activate the site. A site initiation visit (SIV) is generally several hours of time for training, inspections, and administrative paperwork such as the delegation log, training logs, and FDA1572 “Statement of Investigator” form. Most physician Investigators are hard-pressed to even make it to an hour of the SIV – never mind attend the entire visit. I was fortunate to have excellent study staff to work with, and in fact a dedicated Clinical Trials Unit (with their own clinic space and lab) existed to help Investigators throughout the institution. My coordinators included a nurse, and I had a lab tech and study pharmacist team to use too. I was very well supported!

Aside from needing the appropriate mindset to conduct research seriously, and a solid team, there are several areas where Investigators can let their site down, even with the best intentions to heart. Perhaps the most frequent way in which Investigators can get into trouble is agreeing to perform a study that they cannot properly execute. When an investigator is initially approached for a study, they should perform a genuine, reality-based assessment of the feasibility of the protocol. If the blood tests require a -80C freezer, and they don’t have a -80C freezer, then they can’t agree to do the study until they buy one. If the study requires that subjects stay for 8 hours getting pharmacokinetic blood tests done, but their clinical trial unit closes at 4pm, then they can’t agree to do the study. If they only see 1 patient with that specific diagnosis every few months, then they shouldn’t commit to enroll 10 patients in a year. That last issue occurs again and again…I think in a (very) misguided approach to convince the sponsor to allow them to sign-up because they’ll be a “good site”. In truth this is a bad idea, for several reasons. Firstly, site budgets are often written based on the expectation that a certain number of subjects will enroll, and some overhead costs are averaged out over the entire patient mix. Obviously the specifics vary by institution and study budget, but I have certainly heard of sites getting into financial trouble because the investigators would consistently over-promise and under-deliver. Secondly, it makes the investigator look bad – because as much as they can promise the moon, when reality hits they can’t hide it. The CRO and Clin Ops teams will be pushing hard for enrollment, because they in turn are getting pushed by the sponsor for enrollment, and you can bet your bottom dollar that the sponsor is pushing because their Board of Directors and shareholders are pushing for enrollment! Do. Not. Over-promise. Thirdly, and this is a fun little factoid – but the average and typical enrollment data is publicly available. We can tell if a site looks like they’re over-promising, because their enrollment projections will be vastly different from those seen elsewhere in similar studies. I have absolutely seen research sites and Investigators removed from potential study site lists because they were not thought to be realistic.

Investigators can also negatively impact a study by managing their subjects too much like a treating physician. I have heard over and over again something like “Oh, yeah we identified 3 eligible subjects, but they’re not due back in clinic for 3 months.” What? No! So in 3 months you might talk to them about the study, you might give them the consent to review, and maybe they’ll bring it back and sign it in another 3 months? Talk to them over the phone, now, tell them there is a study they might be eligible for – give them any websites or other information (IRB-approved, of course), and you can even email them the consent to read over ahead of time. Bring them in EARLY for a screening visit, separate from their next official medical appointment, go over the consent in person and answer any questions, and if you’re lucky they’ll sign up next week! There is a sense of urgency in clinical trials that simply doesn’t exist in routine medical care. Do not wait to discuss research with your potentially eligible patients and families.

After enrollment, do not manage clinical trial visits and procedures as you would medical care – blood tests might be timed down to the nearest minute, study visits often have allowable windows of only a few days early or late (big tip to schedule study visits early in the window, in case anything happens and you have to delay). You have to be very well organized, and again this goes back to a diligent study staff team. For one clinical trial I was a coordinator on, I created a spreadsheet for all 191 subjects with built-in math to figure out all the required telephone calls and visits that had to be scheduled. A lot of studies these days have similar tools built into the electronic data capture systems to assist site staff with this, but I started back in the day of paper records for clinical trials… In any case, find a system that works and is reliable, and use it! The risks of a lack of diligence and organization are, at the least, protocol deviations and poor data. At the worst, the site can be shut down and the Investigator may be prohibited from conducting research. I have personally seen sites that were put on hold due to serious breaches in Good Clinical Practice (GCP – the rules regarding subject safety and clinical trial execution) that placed subjects at potential risk of harm, all due to a lack of diligence from the Investigator (remember “Clinical” in this context refers to medical research and clinical trials, not standard medical care).

Every Investigator should have undertaken training in the principles of GCP, in fact it is one thing that is repeated for every clinical trial training regardless of whether or not an Investigator has done it before! This training is not entertaining – it is snooze-worthy – but it is very important. The physicians who don’t pay attention to it are the very same ones who are immediately asking for permission for protocol deviations or to skip certain study procedures or visits “because they’re not needed”. If it’s in the protocol, it’s needed. I absolutely urge Investigators, whether would-be, newbie, or seasoned veterans, to pay attention when it is being done. Clinical research certainly isn’t something that should be done in a haphazard or half-hearted way. There is also no room for ego – Investigators and other study staff will make mistakes, Protocol Deviations will occur, misunderstandings will happen. The extremely high standards and rigorous oversight that are required for clinical trials is something that most physicians aren’t used to in their day-to-day practice of medicine, and it can often be misinterpreted as a personal attack or insult to their intelligence. The fact is, we’re really all on the same page, trying to get the best possible data, and keep the subjects as safe as possible.

On that note, the Investigators are responsible for the safety of their subjects. In that regard the opinions and actions of the Investigator matter a great deal. If an Investigator deems that a subject should be withdrawn from a study, they can do that. If an Investigator grades a particular adverse event as mild, moderate, or severe, then we generally rely on their assessment as the clinician who saw the subject (there are exceptions for specific laboratory results or protocol-defined criteria). Investigators assess whether an adverse event is related to the study drug or not. While the Medical Monitor and sponsor can (and often do) request clarification or confirmation of a specific finding, and sometimes even disagree with the Investigator, the Investigator’s assessments are still reported and are incredibly important. Some types of adverse event require very rapid (7 day) reporting to regulatory agencies, and that all hinges on the Investigator’s assessments. It is not unusual for Investigators to reach out to Medical Monitors for clarification or advice, but the Medical Monitors cannot provide patient care and cannot really direct an Investigator to do one thing or another. We can provide information and clarity on the protocol, insight into what the sponsor might think on a particular decision, and discuss any potential protocol deviations that might occur, but ultimately it is the Investigator that makes the final call. I have completed many telephone conversations with the line “I support your decision”.

In that regard I will discuss one final thing that Investigators do that causes issues, albeit rarely – subject unblinding. In randomized clinical trials, the subjects and often Investigators (even the Clin Ops teams and Medical Monitors) are all blinded and unaware of treatment assignment. This is so that no-one contaminates or biases the data from assumptions made of the treatment being given. However, it also happens that subjects occasionally get adverse events that may or may not be study-drug related. There is generally a clause in the protocol that allows for emergency unblinding under certain specific circumstances. That last bit is crucial – because unless it is genuinely thought that (a) the event is linked to the study drug and (b) knowing the treatment assignment will affect the medical management of the subject’s adverse event, there is no reason to unblind the subject! If on month 4 of a vaccine study the subject has a severe stroke, what would you possibly do differently with them, knowing what vaccine they got 4 months prior? Would you use a different brand of tPA? Would you shorten their rehab knowing that they “only” got placebo? No, it wouldn’t matter one iota. Trust me – the subject will be unblinded as part of the final analysis – and often studies have unblinded safety monitoring teams who will look at these type of events separately from everybody else on the study (I have sat on both blinded and unblinded safety monitoring committees for various clinical trials). There is very rarely any rush to unblind as an emergency, and if that is done it actually risks contaminating the data and losing that subject from the final analysis. By all means use emergency unblinding when necessary, but think clearly on whether or not it would actually change the management of the subject or whether it would “just be nice to know”. Do not risk the entire drug approval process just to appease your personal curiosity. It is perfectly reasonable to have a discussion with the Medical Monitor and the sponsor as to whether or not an unblinding should occur, and that can wait until the dust has settled and more information is at hand. Remember, an Investigator can withdraw a subject from a study at any time, and there are allowable reasons to stop study drug while still continuing in the study for safety follow-up. Neither of those options requires unblinding.

Those are highlights of the much broader and more nuanced role of a clinical trial Investigator than I can cover in a single blog post. What I hope I have imparted though, is a sense of how seriously the role should be taken. Investigators are literally the beating heart of clinical research, hugely important, with a great deal of trust given to them, and I found the role to be an incredibly rewarding aspect of medicine, both personally and professionally. I’ll cover how you actually become an Investigator in another post.