Posts Tagged personal choice

The importance of truly Informed Consent

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Uncategorized on April 21, 2024

I heard a little more recently on the contaminated blood scandal of the 1980s, where huge numbers of people with hemophilia were given treatments for their condition that were contaminated with viruses, including HIV and Hepatitis C.

Early on, there was little knowledge about the true risks of these viruses, and no proper testing available (certainly not widely available), but it turns out that some of this story is even worse than simply being given contaminated blood products.

An inquiry in the UK is currently focused on a specific series of infections that occurred at one particular school, which had a hemophilia treatment center on-site and which, it turned out, was also conducting research into novel treatments for the disease. At a superficial level the research seemed sound – it was asking the question: would a new heat-treated version of the clotting factors needed to treat hemophilia be safer than the standard treatments? Unfortunately, the heat-treatment wasn’t sufficient to completely inactivate the viruses – but the story is much worse than just that.

Several people have come forward who not only were infected with the viruses anyway, but possibly didn’t need treatment for their hemophilia at the time they were given the experimental treatments and, worse, neither they nor their parents were properly consented for the research. When the true risks of infection were obvious, subjects weren’t told, and some weren’t even informed of their infections for a year or more. One doctor involved in the study, a Dr Samual Machin (now deceased) is quoted during the inquiry:

“This would have been discussed with his mother, although I acknowledge that standards of consent in the 1980’s was quite different to what it is now,”

At the time, the subjects were all children, and several of the parents denied being properly told about the research, and that they would not have consented had they been told. Further documents showed that untreated patients were highly sought after, and that trying out the new heat-treated therapy may have been prioritized over the patients actual medical needs.

There are several core principles of research at stake here – beneficence (doing good), non-maleficence (do not do anything bad) and autonomy (being able to make your own decisions). Even a cursory look over the stories of this case show that none of those principles were upheld in this research, and of course the fact that the heat-treatment didn’t work to inactivate the viruses makes it all the worse (arguably if the research was a stunning success there wouldn’t be an inquiry into any of this…but that’s a whole other topic for discussion).

While there are regulatory rules for ensuring proper scientific conduct of research, there are also ethical rules. The two have some overlap, but they really are distinct frameworks, within which researchers have to function. The sad fact is that many of the rules and protections that we now take for granted were imposed as a direct consequence of past unethical human experimentation (which leads to another discussion about how what is considered “ethical” changes over time). From the perspective of human subjects and safety in particular, these are reflected primarily in the document we know as the ICF – the Informed Consent Form.

While it’s true that many aspects of subject safety, rights, and welfare are contained within the research protocol, the protocol itself is a highly technical description of the research and as more of a scientific justification and research plan. The ICF on the other hand is intended to be seen and understood by the study subject themselves, and includes a discussion on the research protocol (visits, procedures, timeline, risks etc.) in addition to making them aware of certain other rights afforded to them, including the right to leave the study at any time and any other treatment options available. The research site’s institutional review board (IRB) would have reviewed and edited the ICF to ensure that it accurately reflected the research risks and benefits prior to being seen by a potential subject. IRBs include subject-matter experts as well as members of the lay public to ensure clarity and understanding. Not only are potential study participants supposed to be given the opportunity to ask questions before signing the ICF, but they receive a copy and a copy remains in their medical record.

The fact that no such process occurred in these contaminated blood product studies is obvious.

Unfortunately, stories like this from research done decades ago, and which clearly doesn’t meet current standards, color everybody’s opinion of medical research. I have had parents refuse to consent for a study because “The sponsor is [insert drug company with research scandal] and I don’t trust them,” even though the drug in the study had nothing to do with the risks from the older scandal. I heard about one parent who turned down a study because of a poorly written ICF, that ironically overstated the risks in a summary paragraph that implied the drug had never been given to anyone before – some people might have continued reading, but this parent did not (they did however provide that feedback to the investigator, so we were able to modify the ICF to make it more clear). One time I had a sponsor try to avoid explaining all the risks (for the control therapy, not the study drug) in the ICF and instead provide a patient hand-out or “your doctor will explain this to you” verbiage. Despite our warning that the IRB would reject this ICF, they insisted on submitting it and of course wasted a whole IRB review cycle as they were forced to revise and resubmit the document with our recommended wording. This wasn’t an intentional thought to mislead, they genuinely thought it was a more efficient process and would avoid scaring the subject unnecessarily, but we knew that the ICF should be a stand-alone record of the subject being truly informed before consenting.

One of my experiences with obtaining consent sticks out to me – it was a slowly-recruiting antibiotic study and I was hoping to not have another screen-failure at my site. I had found a possible subject and was discussing the study with his mother and my study nurse. The mother was asking careful questions, clearly a little nervous (her son was in hospital after all!) and I was thinking that she probably wasn’t going to sign him up when she suddenly said “You know what, you’re the doctor and you know best, I’ll do whatever you say.” Massive red flag to me, as an investigator. Research isn’t the same as medical care – if “I knew what was best” we wouldn’t be having a conversation about a clinical trial! Also, if something were to happen during the study and she had rescinded the decision to me, then she as a mother would feel far worse than if she had made the decision truly believing she had made the best call. So I called “Investigator fiat” and screen-failed them. Every set of inclusion/exclusion criteria includes a line about “any other condition which, in the opinion of the Investigator. would interfere with the conduct of the study” and at that point I’m not sure that she fully understands the risks and benefits.

While we might celebrate some of these stories as holding ourselves to a high standard, the sad truth is the current standards of oversight and training that we have in medical research are much better than they were in the past mostly because of how poor they were in the past. Personally, I find it shocking that some of this occurred within my lifetime, and I think it behooves us to be mindful every day about how we conduct our research, placing the rights and welfare of our participants first.

When it really is a virus

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Bacteria, EBM, Infections on November 30, 2012

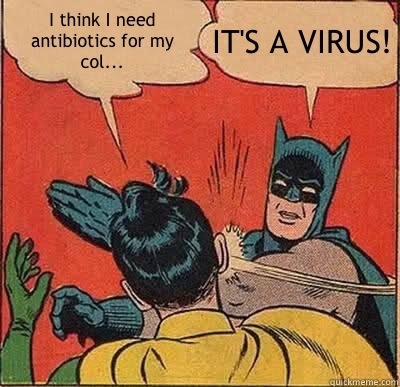

I joke that, as a Peds ID doc, it is my duty to say this at least once a day…

Ok, I may not literally be slapping people upside the head, but there are certainly times when I’m doing it in my mind. The situation is common enough – a patient, parent or doctor, faced with symptoms consistent with an infectious disease, considers using antibiotics to treat bacteria. After all, we know that bacteria kill people, right? But in many of these situations the patient really has a viral infection – and viruses aren’t affected by antibiotics. So at the very least we’re wasting money and drugs. Worst case scenario? We’re promoting drug-resistant bacteria, antibiotic allergies and side effects – that in some cases can be life-threatening.

But aren’t there clues to help us make the distinction? Real clinical signs and symptoms? Well, lets review a few.

White pus on the tonsils

Everyone is familiar with the feeling of an awful sore throat, and having a doctor peer down and having you say “Ahhhh…” What are they looking for. Probably something like this:

This is a classic appearance of “Strep Throat” – a bacterial infection that aside from being painful in its own right can go on to lead to serious complications, such as rheumatic heart disease, kidney disease, a form of arthritis and a weird neurologic disorder called “Sydenham’s Chorea”. Fortunately it has no drug resistance so simple penicillin/amoxicillin will kill it (so if your doc tries to give you “stronger” antibiotics please feel free to slap them).

The trouble is, this isn’t a picture of strep throat. I grabbed this from an article on “Mono”. Infectious Mononucleosis can be indistinguishable from strep throat, but antibiotics do nothing for it. The “pus” you see isn’t really pus, it’s just a nasty-looking white gunk your tonsils make. A bad sore throat can be caused by influenza, adenovirus, RSV, metapneumovirus, rhinovirus….you get the idea. It can be hard to tell strep throat from any of the other many possibilities, but in general if you DON’T have a runny nose or a cough, and the lymph nodes in your neck hurt then it’s PROBABLY strep. But it could be a virus. Strep tests and cultures help – and holding off on treatment until the test comes back is a sensible plan.

Red eardrums

What about ear infections? Another common bane of pediatrics (almost every young child I see with a prolonged illness has at some point been diagnosed with an “ear infection” before arriving at the correct diagnosis – I once saw a kid with a brain tumor get that diagnosis…). The symptoms are notoriously non-specific (ear pulling, fussiness, fever) and a good ear exam in a small, squirming child can be difficult! A crying baby can turn their ear drums pink…and voila! An ear infection! But even assuming your exam is good and the ear drum really does look nasty, how do we know its a bacterial infection? Despite the appearance of a rip-roaring otitis media (bright red, bulging ear drum, fluid behind it) it can be a viral infection too. Most of what you see is the BODY’S response to the infection remember. Clinical trials of antibiotic use have shown with without antibiotics, ear infections tend to get better just as quickly as with them. Complications from untreated bacterial infections do exist, and can be quite serious, but are rare. It is prudent to consider a “wait and see” approach to ear infections to see if it gets better by itself. I don’t want your kid to get mastoiditis any more than you do, but if it does happen I want it to be treatable with the best antibiotics!

Most of the time when we’re treating ear infections we’re not even treating the child…we’re allowing the adults in the house to get a good nights sleep…;-)

Cough, fever, patches on chest x-ray

Pneumonia? Guess what. Usually a virus, at least in kids, before they become immune to everything. Without proper testing though this can be harder to tell apart, and we’re getting into the realm of “sick kid” here. Almost every doc will feel a little weird ignoring a possible bacterial pneumonia, even if they really do think its viral. But the high rate of viral infections, along with the risk of increasing drug resistance, is why the current recommendations for antibiotic treatment of pneumonia in children start with plain old amoxicillin. RSV, metapneumovirus, influenza, adenovirus – they can all cause pneumonia. In the Bad Old Days viruses like measles and varicella could also do it, and they were quite nasty! With symptoms like a runny nose, rash, lots of sick contacts, the chances of it being a viral infection are quite high. Sitting it out for a few days is again a reasonable option – because you know if you see a doc and get a chest x ray they’ll start you on antibiotics, and we don’t want that, right?

Very high fevers, difficulty breathing, chest pain with pneumonia, coughing up junk – always worth getting checked out.

Green snot

All of us have at some point experienced symptoms of a sinus infection. Fever, pressure, tons of snot, headache. They are truly miserable things. I hear all the time how “we knew it was bacterial because he had green snot”. Sorry, but that’s not all that helpful. The greenness of snot comes from the cells your body is sending in to kill the infection, which will tend to be neutrophils whether it’s a virus or bacteria. (Neutrophils don’t really kill viruses, but they’re just reacting to the inflammation there). Neutrophils have the awesome ability to create highly-reactive chemicals, one of which is called “superoxide” which gets converted to hydrogen peroxide which then reacts with chloride ions in salt to produce….bleach. The green color you see is actually the neutrophils and the enzyme they are using to create the bleach (myeloperoxidase), not the infection itself. You’ll get green snot regardless of what’s causing the infection, and it’s a good sign – a sign that your immune system is in full swing.

Severe sinusitis will produce lots of snot, for sure, but lots of snot doesn’t necessarily mean its a severe sinusitis, and certainly doesn’t prove it’s bacterial. If symptoms have lasted for a couple of weeks with no improvement, that’s a red flag for something non-viral.

High Fever

Fever is a normal immune response which effectively suppresses bacterial and viral infections. It hurts them far more than it hurts the patient. A fever by itself won’t necessarily cause any harm at all – and high fever may or may not indicate bacterial infection. A fever is just a clue – a reason to look and figure out what’s going on. One you’ve figure out it’s a virus based on symptoms (runny nose, viral rash etc) then you’re good. And don’t worry if fever keeps coming back, it will do that until the infection is gone, which may take a week or more.

The height of the fever is only slightly predictive of the risk of bacterial infection – but influenza, adenovirus, EBV can all cause pretty good-going fevers of 102F and up. I’m far more interested in what ELSE is going on in addition to the fever.

Febrile seizures, convulsions caused by fevers in young children, are more closely associated with a rapidly rising fever than a high fever itself. If your child has a fever of 104.5F and has sat there for an hour, chances are good they’re not going to seize from that.

Addendum – Mark Crislip recently posted on fevers over at Science Based Medicine!

Summary

So that’s a rough overview of the various common viral infections. It really is surprising how often we do get sick from something that will simply run its course. Our immune system is pretty robust. That’s not to say that in exceptional circumstances viruses can’t or shouldn’t be treated (herpes, influenza, chickenpox, measles, adenovirus, CMV and EBV all have some form of treatment to try even if the therapies are nowhere near as effective as antibiotics are on bacteria) but for respiratory infections in particular we would be far better served by reassurance that our symptoms are more consistent with a virus than a bacteria, and that most of the time it will sort itself out. A large chunk of the inappropriate usage of antibiotics stems from over-treatment of viral respiratory infections – so next time you see your doctor for something like this consider asking about tips for symptomatic relief rather than an antibiotic prescription.

A few other studies: prescribing antibiotics doesn’t necessarily save time.

Antibiotic overuse, even based on physician diagnosis, worse with criteria-based diagnosis.

Understanding why physicians overprescribe – many different reasons.

Good advice can be found on the CDC website.

I have been told that I must credit my wife for originally coming up with the idea for the “IT’S A VIRUS” slapping Batman meme, and Quickmeme helped me create it.

Vaccines, choice, and training rabbits

Posted by Nick Bennett MD in Antivax, Patient-Centered Care, Personal Choice, Public Health, Vaccines on August 7, 2011

Just for a moment I’m going to take the view that vaccines are, you know, safe and effective. Sure, there are known side effects, mostly mild short-lived things like injection-site reactions or fever, but Bad Things do happen (e.g. Vaccine Associated Paralytic Polio from the live oral polio vaccine). On balance though it is clear that the benefits of vaccination to society as a whole outweigh the risks to society as a whole. Their success is measured in what we DON’T see – the 20,000 HiB cases a year, the 80-90% drop in pneumococcal disease from vaccine strains, the congenital rubella cases that every medical student knows how to spot (“Blueberry Muffin” baby, cataracts, persistent ductus arteriosus) but will likely never see in their professional lifetime. Safety monitoring is there, as imperfect as it is, which is why for example we don’t have oral polio vaccine in the US any more, and why the first rotavirus vaccine was pulled from the market.

So if we were to take a purely logical view on the matter, vaccination is a no-brainer. For many Docs this is why they get so irate about vaccine refusers. We learn about the diseases and the successes, and find it hard to fathom how you could come to any different conclusion. But clearly people do. There are unfounded fears about “too many too soon”, or aluminum adjuvants that add less exposure than breastmilk, or the fraudulent claim of autism causation that ended up being a scam for one Doc (the infamous Andrew Wakefield) to sell his own measles vaccine. Some parents are simply worried based on a previous bad reaction (I know I was, based on the way my eldest acted after his 2 month shots). Others have a genuine religious belief about medical interventions, and vaccination is just one aspect of that.

So then we run up against the problem of how to deal with this issue. As a general rule of thumb, it is accepted that a patient has the right to refuse aspects of their healthcare. There are very few exceptions to that rule, usually in the interests of others in society – forced hospitalization of mentally ill people who pose a threat to themselves or others, or cases of medical neglect where the State assumes responsibility for the medical decisions of a child when the parent puts them at risk, or Directly Observed Therapy for TB, where optimal treatment is paramount and doses should not be skipped. Things like that.

But vaccines are put into a different category. Why? I think the biggest, most obvious difference is that we’re not talking about treatment of someone with a disease, where inaction has obvious consequences, but rather an intervention to a typically healthy individual. In fact, moderate illness (enough to require hospitalization) is one reason to consider delaying vaccination, as the immunization might not work as well. As such, even though the results of inaction can be severe, resulting in death or disability, and inaction certainly has an impact on others in society, there is a natural reluctance to literally force vaccination upon people. Instead, there are more insidious ways to encourage vaccination through school mandates etc. Vaccines are not mandatory, you just have to get them. (If you can understand that, let me know, as that was how a non-mandatory examination was explained to us in medical school…)

As one approach, I am going to use the analogy of rabbits. Above you can see Princess Lulu Merryweather, an Old English Mini-Lop who was with us for over 8 years before succumbing to a pasteurella abscess. Lulu was a house rabbit and was pretty much housetrained. She knew a basic list of commands and would poop in her cage. The training of a bunny is interesting – as a prey animal they do not respond well to the typical training one might use with a predator animal such as a dog or cat. They are more like a horse, and respond best to coercion rather than discipline. In fact, an effective way to get them to do what you want is to embarrass them. This is difficult to do. It generally involves stamping your foot, turning your back on them, but trying to make eye contact so you know that they know that you are displeased. If you’ve ever had a bunny and told them off for something, you’ve probably seen them do this to you. There were several occasions when, as a kitten, she would pee on the couch and we would both end up stamping and back-turning on each other as I would tell her not to do that, and she would try to tell me not to shoo her off the couch. It was her couch, after all. (Did I mention the “Princess” part was added later? It was more a description than a title…)

So, since the decision not to vaccinate is often based more on emotion than logic, it seems reasonable that for some people (not all of course) an emotional approach will work better than a logical one. Human beings are hard-wired to fear bad things from an action (to vaccinate) more than from inaction (not vaccinating), even though a decision to do nothing is still technically a decision, and fear after all is an emotion. I wonder then if pressure from society, an explicit message that says that unvaccinated kids are an unacceptable risk to others would work. Peer pressure. At the moment we have an attitude of tolerance on the whole – barely more than a raised eyebrow, more often a nod of understanding. There may be pressure from the Docs and schools who are trying to protect society from itself, but there needs to be a grass-roots movement among the parents in my opinion.

I’m not entirely sure yet how exactly to go about doing this. I don’t agree with literally holding a parent back while we forcibly inject their child – since after all we do live in an age where many of the preventable diseases are at very low levels, and that goes against every fiber of my “patient-centered” being. I would much rather have informed decision-making – I just realize that for many their mind is made up no matter what facts I lay out and what misconceptions I correct. What I would like to see is an attitude of personal responsibility to temper the push for personal freedoms. Parents should WANT to vaccinate. Currently most fall into the “I don’t care” or the “I don’t want to” camps. That kind of paradigm shift may be slow coming, and I’m open for suggestions on how that might occur. We can’t use a stick, we need to use the carrot.

And maybe some foot-stomping.